The new ‘too normal’ — AI’s band plays on

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

I am a lousy typist. At my fastest, I use six fingers and a thumb, while looking at the keyboard.

My inability to type is only exceeded by my horrible handwriting.

Despite these handicaps, thanks to communication technologies, I became an academic and a writer. For years, that meant producing everything laboriously on a manual typewriter, with puddles of correcting fluid and mountains of erasable paper. But things changed.

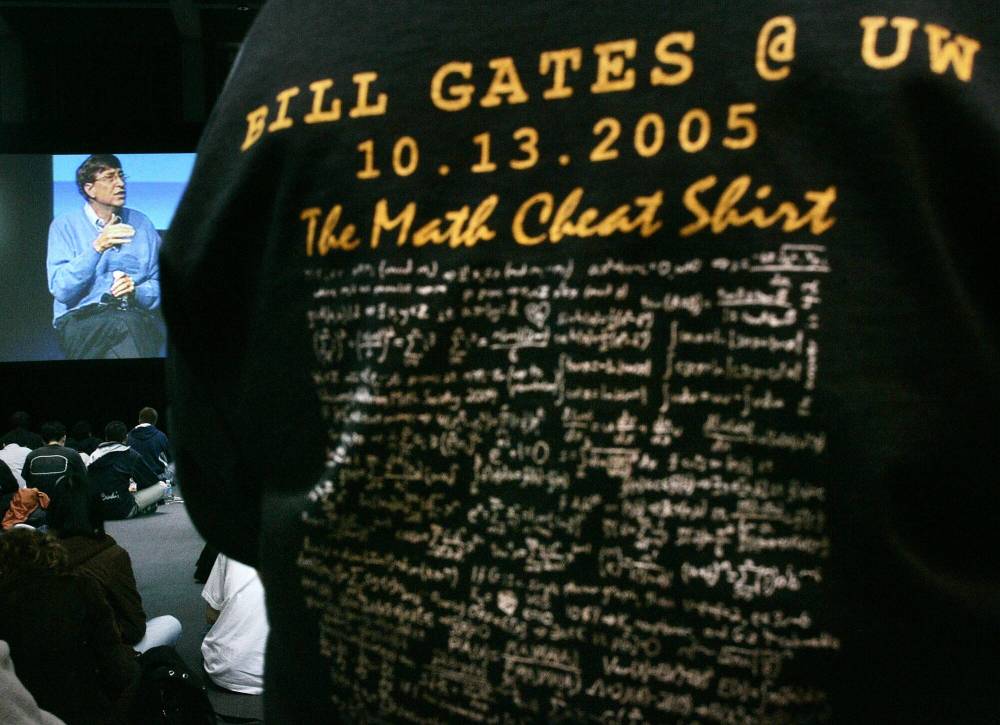

Adrian Wyld / The Canadian Press

Columnist Peter Denton has a long and fractious history with Microsoft and Bill Gates (shown here on a broadcast at the University of Waterloo in 2005).

Back in 1984, I remember the sheer joy of producing my MA thesis on an Osborne 1 university computer that I was allowed to use after hours. When I discovered it even included automatic footnotes, I decided the world of computers was a mighty fine place.

Things continued to change. Spell-check was a further gift, as my fingers kept refusing to spell things correctly, but grammar check was a constant irritation. Those green lines kept appearing in all the wrong places, as the Microsoft editor (who failed first year English) rejected stylistic options as grammatical errors — but at least it could be switched off.

While I have fumed since 1990 about how such features threatened to turn creative writers into clones of Bill Gates, artificial intelligence (AI) has recently made the situation much worse, almost overnight.

My badly typed drafts were always in need of correction, so the delete key became my new best friend. But, these days, I can make far worse mistakes than a simple typo.

Gone are the amusing times when student resumes would proudly claim their skills in “pubic relations” or “costumer service.” Autocorrect is rapid and potentially lethal — before I can correct my frequent typing mistakes, the latest AI-enhanced version of Microsoft Word has helpfully inserted the word I must have meant to type, instead.

These enhancements are both insidious and inescapable, especially now that Microsoft Co-Pilot has been embedded in Microsoft Office. I need to reread everything I write very carefully, to make sure that my (often lewd) co-pilot doesn’t crash the literary plane. I also remain irritated at having constantly to override the grammatical “suggestions” that render mildly amusing, original prose into the drab, dull monotony of whatever now passes for acceptable English at Microsoft HQ.

“Iatrogenic” is the bafflegab word that means doctors or their treatments made you sick. We need something similar (AI-trogenic?) for what AI is doing to our language and to our writing.

’Iatrogenic’ is the bafflegab word that means doctors or their treatments made you sick. We need something similar (AI-trogenic?) for what AI is doing to our language and to our writing.

To sum up all these computerized changes with enthusiasms about undeniable progress, we have inaccurately labelled it as “generative AI,” an exciting new creative tool that uses “large language” models to enhance our ability to communicate and improve our work.

In reality, we should be calling it “regurgitative AI,” using electronic censorship to shrink our communication down to the lowest common level, requiring diminishing ability either to create or consume it.

AI does not produce new ideas; it rummages about on the internet and finds whatever is out there, neatly repackaging it for the unwitting (or dimwitted) consumer by an algorithm designed in secret for what we hope are good reasons.

AI does not produce new ideas; it rummages about on the internet and finds whatever is out there, neatly repackaging it for the unwitting (or dimwitted) consumer by an algorithm designed in secret for what we hope are good reasons.

All this confirms my first lesson in computer science, back in the dark ages of 1975: “Garbage In; Garbage Out” (GIGO). Yet everyone seems to be jumping on the AI bandwagon, whether or not they know what it is, or where it is headed.

We are not all idiots, incapable of ever writing well, but the producers of AI systems want us to think that. The consequences of this attitude for education are potentially devastating:

First, AI is not being used to improve the quality of students’ work, but to dodge work altogether. In the past year, I have witnessed an explosion of cheating on assignments, enough to require dramatic changes in my teaching. (In one course, I have even reverted to in-class work, all done by hand in exam booklets, under my direct supervision.)

Second, AI is pervasive at all levels, including graduate school. High marks are no longer an indication of excellent work, which is ironic: Students using AI to improve their grades will find their transcripts doubted, without confirmation. Every job interview will soon begin with a pen and paper — expecting the applicant to read, understand and answer a narrative question, in good English, unassisted.

Third, much of the automatic AI help is not required. Not every search requires AI, nor does every document require AI editing. All this adds up to an astronomical social cost in terms of data centres, electricity and water usage for things we should learn to do ourselves.

Worst, Shakespeare would be horrified at the computer-enforced language compliance that erases our linguistic creativity. The words we write should be original, not obligatory.

For example, I just thought up a new one: “pharking” — the often-frustrating experience of using an app on your mobile phone to pay for parking. (Try using “pharking” online, and see how quickly it gets accepted!)

Writing and thinking are skills we each need to develop and use, or nothing really changes.

Peter Denton types poorly (still) from his home in rural Manitoba.