Disillusionment, despair, disgust The deepening and complex homelessness crisis, spreading encampments and dearth of effective responses are pushing city neighbourhoods to tipping point

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

On a calm summer day, the Red River serves as a mirror, its glass-like surface masking the muddy bottom below.

Look closer and you’ll see a reflection of the city along its banks. Towering cottonwoods and elms, riverside homes, iconic postcard backdrops.

Look closer still, and the city’s scars — from the physical and psychological of individuals to the enabling and failings of institutions — are laid bare.

What begins as a trickle near Kildonan Park grows into a flood the further south you travel along the river.

Tents, tarps, trash.

Shopping carts — some abandoned, some overflowing with detritus. Makeshift firepits, piles of scrap metal, scavenged mattresses. A dystopian world of despair.

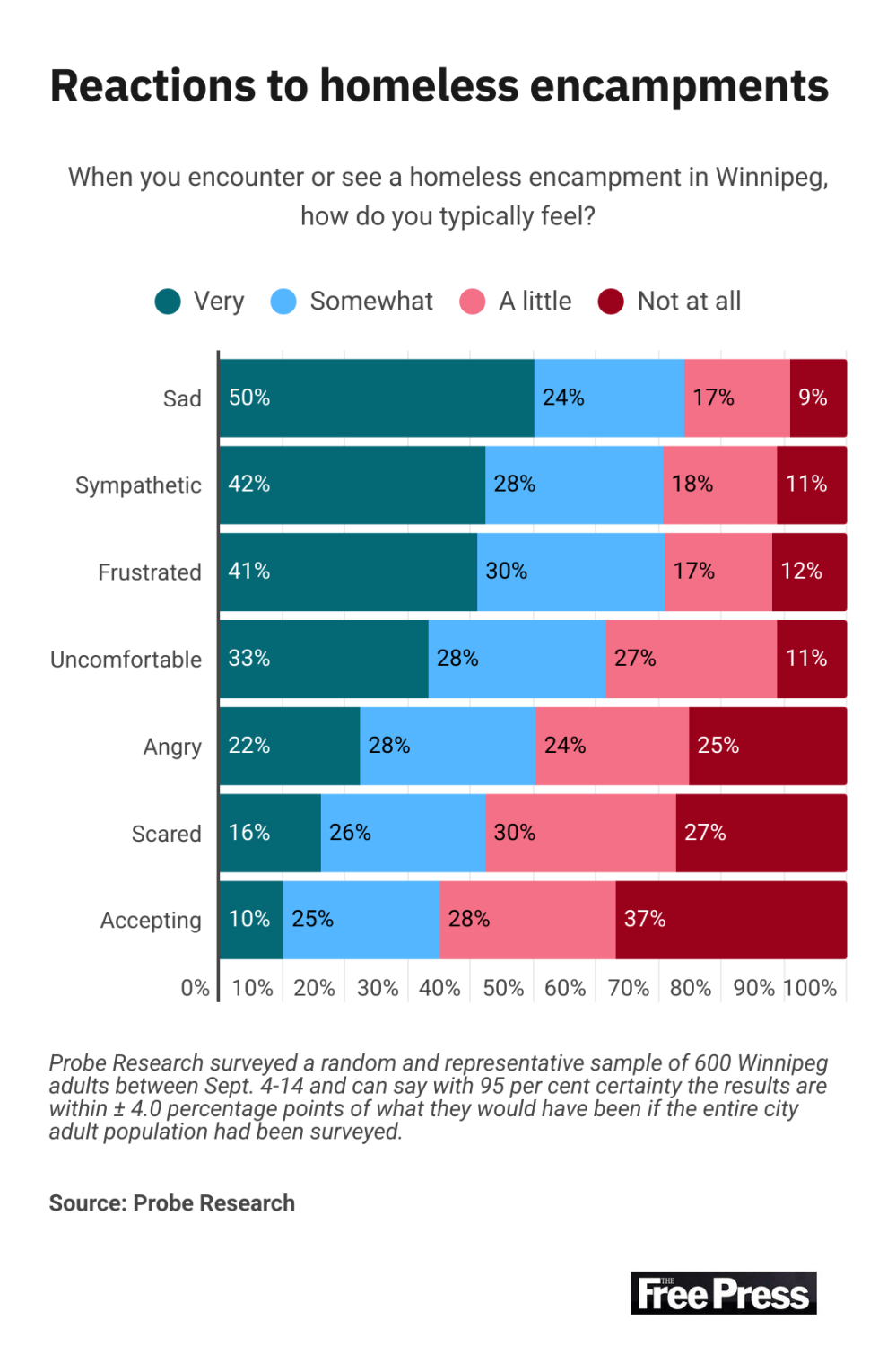

As Winnipeggers know, the river carries many secrets; notably its murky waters move deceptively fast. There’s another undercurrent percolating just below the surface — a city growing increasingly more frustrated by the lack of progress on the homeless file.

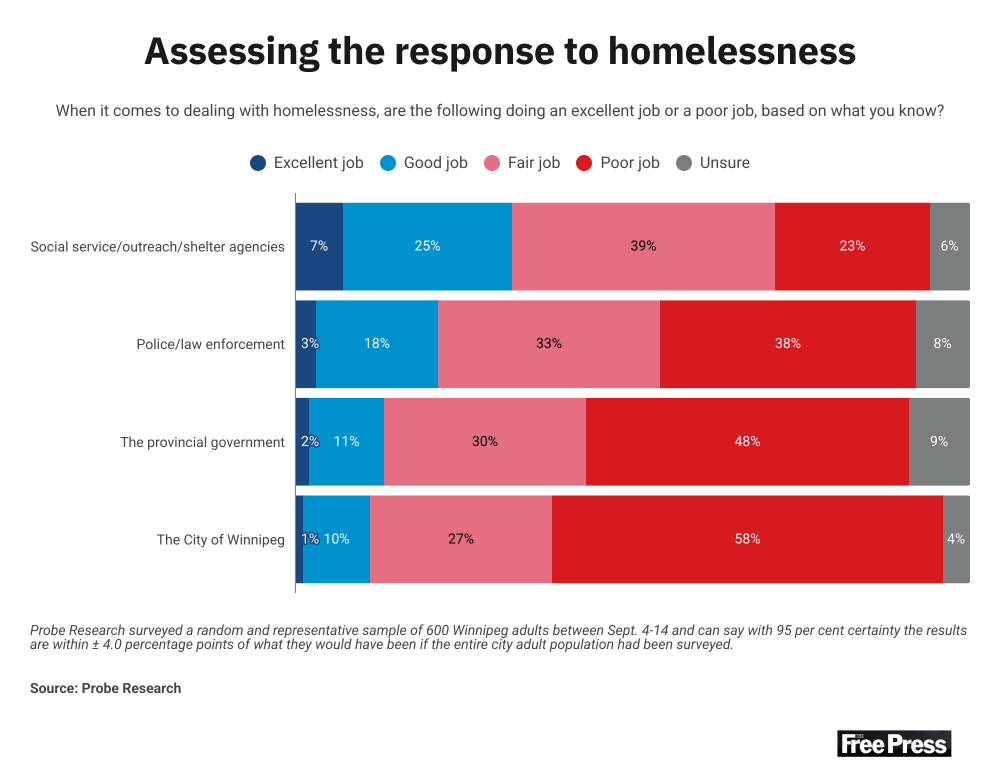

According to a new Probe Research poll commissioned by the Free Press, a majority of Winnipeggers have lost faith in government, law enforcement and front-line agencies tasked with dealing with the homeless crisis.

Only one in 10 respondents believe the city is doing a good job; only two in 10 support the efforts of the police; and only three in 10 believe social agencies are making a difference.

In the city’s case, 58 per cent of Winnipeggers have given the municipal government a failing grade (a seven-percentage point increase from only a year ago).

The province fares marginally better, though nearly 50 per cent of respondents believe Premier Wab Kinew’s government has done a poor job.

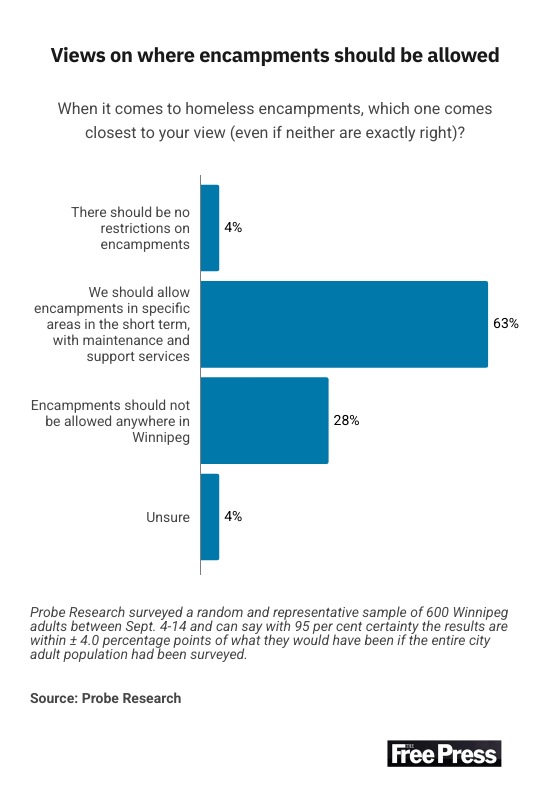

The public’s mood is beginning to be mirrored in moves at city hall. On Thursday, council voted unanimously in favour of restricting where encampments can go, barring them from playgrounds, schools, day cares, recreation facilities, parks, near bridges, rail lines or transit shelters.

It’s a policy backed by Winnipeggers — with six in 10 believing encampments should only be in specific locations, with maintenance and support services in place, but only for a limited time.

Meanwhile, nearly three in 10 believe encampments should not be allowed anywhere in the city.

In a letter to several media outlets this summer, an East Exchange resident whose condominium is a short walk away from one of the largest riverbank encampments expressed her frustration at the lack of progress.

“Due to the city’s so-called ‘compassionate’ hands-off approach and (front-line agency Main Street Project’s) enabling and perpetuating homelessness these past five years with its ‘human right’ mantra, too many people in this city… do not understand the reality of encampments, the damage they have wrought on those who live in them and those who live in proximity to them,” the resident wrote.

The challenge facing Winnipeg is not new. But post-pandemic and amid an escalating toxic drug and mental-illness crisis, it’s reached a tipping point. The number of homeless people, double from two years ago, and the spread of encampments, no longer just dotting riverbanks, are unprecedented.

What began as a humanitarian challenge is increasingly becoming divisive on multiple levels this year — from the mayor questioning the actions of one front-line group, to in-fighting between social agencies, to distrust of police and pushback against their presence.

Frustration is rising, patience is wearing thin, the undercurrent is getting stronger.

As the river flows north, it wends tightly around a neighbourhood that has experienced more than its share of misery.

When Winnipeg, fuelled by the railways’ powerful economic engines, was burnishing its reputation as the Gateway to the West at the turn of the 20th century, Point Douglas and other neighbourhoods on the wrong side of the tracks became home to slums, poor sanitation and disease.

Today, Point Douglas remains one of Canada’s poorest neighbourhoods, its land among the most toxic in the city due to industrial waste. In recent years, its residents have fought back against crack houses, gang activity and a proposed supervised drug consumption site, so it’s not surprising there’s a weariness in their voices when they talk about how daily life has become a constant struggle to balance compassion with concern.

The explosion of homeless encampments dominates conversations at community mailboxes and corner stores — as well as in private and public social-media forums meant to keep neighbours informed and on guard.

“We are watching a human catastrophe right in front of our eyes,” says one of several residents who recently sat down with the Free Press to voice their concerns.

They share many similarities — including a reluctance to be publicly identified, fearing backlash for speaking out on the sensitive issue.

One woman has lived in Point Douglas for a decade and says she barely recognizes her community anymore. The single mother of young children has armed herself with a steak knife to scare away a late-night intruder, been confronted in her garage by a man wielding a machete, found another swinging a crowbar in her backyard, and had to console her son after he was punched while walking to buy maple syrup for Sunday morning pancakes.

“We are watching a human catastrophe right in front of our eyes.”

Broken glass, discarded syringes and the smell of smoke from fires are daily hazards. Recently, another unexpected hazard emerged: raccoons sick with distemper, including one that bit her dog — resulting in a $1,500 vet bill.

“It’s from all the garbage being left around the encampments,” she says, noting police and animal-control officers have had to euthanize raccoons on the spot.

She scrolls neighbourhood Facebook pages where residents post surveillance footage of crimes in progress, including middle-of-the-night thefts by individuals emerging from riverbank camps.

“You’ll be driving down the street past an encampment and be like, ‘Oh, there’s your barbecue, there’s your chairs,’” she says. “They even uprooted an entire cement bench from a park. I don’t know how they had the muscle to do that.”

Other recent alerts have involved a naked, distraught homeless man wandering near an elementary school.

“It’s now to the point where we don’t even bother calling police for the majority of things,” she says, noting the so-called “broken-window theory” is playing out in real time.

“The residents here have been pushed too hard for too long. It’s been exhausting,” she says.

At the top of her list of frustrations is being branded insensitive for speaking out — particularly by groups such as Main Street Project, the city’s largest homeless shelter and outreach agency. She and others accuse the organization of failing to manage the situation while adopting a “holier-than-thou” attitude.

“To them I’d say, ‘Can we do a house swap for a week?’ You can come and live here to see what it’s like,” the woman says.

Her close friend believes Point Douglas residents have been left to face the crisis on their own.

“We are having to come up with ways to secure our homes, to feel safe in our communities,” the second woman says. “Where is the plan for the safety and security of people like us, to maintain order and to prevent harm for us?”

The Point Douglas Residents Committee, a grassroots advocacy group, recently wrote to Winnipeg police asking what criteria determines whether details of encampment incidents and arrests are publicly released. They believe the data is being deliberately suppressed.

The police’s answer? File an access-to-information request, a response the women say only reinforces residents’ sense of being abandoned.

The second woman recently had an encounter with a homeless man in her yard; she politely asked him to leave. “I’ll leave when I (expletive) feel like it,” he told her. “I can be anywhere I want. Go (expletive) yourself.”

“We’re in a crisis here. It just seems to be a free-for-all. And what they’re doing obviously isn’t working.”

Like her friend, she is sympathetic to the struggles of people on the street but believes the pendulum has swung too far in the wrong direction.

“When did kids not become a priority for protecting?” she says.

Beyond her personal safety, she also worries about the well-being of vulnerable people in encampments. She recently encountered a young woman who had immigrated from Africa, became addicted to methamphetamine, and was sexually exploited and trafficked while living on the riverbank.

“Why is this woman, new to Canada, already on the street? There’s so much exploitation going on,” she says.

“They call them survival crimes. Excusing crime that needs to be done for survival. Well that’s a pretty slippery slope, don’t you think? What kind of a society do you want to have?”

Both women say they’ve tried to show compassion — dropping off food, clothing and blankets for people living rough. But when they and other residents voice concerns, they’re vilified.

“We’re in a crisis here. It just seems to be a free-for-all. And what they’re doing obviously isn’t working,” the second woman says.

As spring turned to summer, bikes, frames, wheels of all shapes and sizes and a mishmash of parts spread like weeds through the riverbank undergrowth.

A chop shop of Franken-ized bikes was in plain view of anyone walking or cycling along the crushed-gravel path running parallel to the river heading into Point Douglas from Waterfront Drive.

In late August, Winnipeg police executed a search warrant of a wooden-frame structure at a riverbank encampment and seized dozens of bikes and components. Two men were charged with possession of property obtained by crime.

It was the first time police obtained a search warrant for a structure in a homeless camp.

Days before, two senior officers sat down for an interview to discuss law enforcement’s role in navigating the homelessness crisis.

It’s a delicate dance between enforcing the law, trying to work co-operatively with front-line agencies and government officials, meeting the expectations of an increasingly frustrated public, and dealing with hostility and distrust among the homeless.

“People want this to be a police issue, and they want us to simply go in and remove the camps,” says Insp. Helen Peters, the divisional commander of the Winnipeg Police Service’s central district. The problem, she says, is that living in an encampment is not a crime.

“The last thing we want to be is jackboot thugs coming in at the end and dragging people out of tents,” deputy police chief Scot Halley says. “That’s not our role.”

It’s a sensitive subject within the service, particularly in the wake of last September’s death of Tammy Bateman, a homeless woman experiencing mental-health and substance-abuse issues who was struck and killed by a police cruiser.

Police were harshly criticized by advocates and Indigenous organizations who questioned why officers were driving at night through a Fort Rouge riverside park where Bateman had been living.

The incident remains under investigation by the province’s police watchdog, the Independent Investigation Unit of Manitoba.

“The officers involved were devastated by that,” Halley says. “I think it did impact our relationship with people in encampments. The officers had no intent there. It was just a really tragic event, and I think we’ve been able to continue to move forward and continue to build relationships.”

In the aftermath, police have been rethinking their role, in consultation with social agencies, though Halley concedes it hasn’t been “an entirely smooth process.” Senior management is working hard to communicate the protocols members are expected to follow when it comes to dealing with encampments.

Social agencies lead the response, connecting people with housing and additional supports. Police step in when it’s a criminal matter or safety is at risk, Peters says.

Officers still make “non-threatening visits” aimed at building relationships, Halley says, though for now the approach is mostly reactive, with police responding to calls for service along riverbanks — noise complaints, disturbances and similar incidents. But because they are typically given a low-priority designation, that further fuels public frustration, Halley says.

“The last thing we want to be is jackboot thugs coming in at the end and dragging people out of tents.”

“People get frustrated because they perceive an encampment as impacting their lives and their ability to enjoy their neighbourhood. We completely understand that,” he says.

“We are dealing with it, but maybe not in as quick a way as or in as visible way as they will see it. Our officers feel it. If they could just make the problem go away for people, they would absolutely want to do that, but I think there’s another way to do it, a more humanitarian approach, for sure.”

It’s a challenge most Canadian cities are facing. In early September, the mayor of Barrie, Ont., declared a state of emergency over public-safety concerns and the “lawlessness” of homeless encampments. It’s a decision other cities have considered this summer, as well.

Winnipeg officials — despite the scale of homelessness exploding in recent years — have not considered such a drastic move.

Police are part of a larger network that includes city and provincial officials, fire and paramedic services, and social agencies. Together, they meet regularly and prioritize which encampments to address first, often focusing on the largest or most problematic sites.

It’s a slow, methodical process with few immediate results. Without shelter and supports in place, simply removing an encampment only shifts the problem to another part of the city, Halley says.

According to the 2024 Winnipeg Street Census, it’s estimated a record 2,469 people were experiencing homelessness in the city — nearly double the amount from two years earlier — with about 700 living in encampments. Nearly 80 per cent of people experiencing homelessness are Indigenous.

Some are desperate for housing, some are resistant to living within four walls, and a smaller group are “troublemakers” preying on the weak and vulnerable, a fact that’s particularly worrisome in a city considered ground zero for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

“Not every individual in an encampment is a poor, desperate soul that is wanting housing,” Halley says.

In early September, police assisted in the removal of a small camp in Central Park after receiving complaints of discarded syringes from community organizations and parents of a nearby day care.

That incident underscores the competing tensions at play in the homelessness crisis — the public’s right to places and safety versus an individual’s. The park is considered the “backyard” for thousands of inner-city families; for one of the women removed, it was the loss of a perceived safe place.

“Where am I supposed to go?” the woman asks. “The riverbank? It’s dark there and I’m alone. I’ll be sexually assaulted out there.”

As our motorboat makes its way upstream towards downtown, not everyone is in a talkative mood. Several residents at a large encampment near the Redwood Bridge wave us away. Their home is marked by dozens of shopping carts, clustered together as closets, barricades and even docks.

A shirtless man hacks away at brush beneath a yellow Corona umbrella on the hot, humid afternoon.

Clothing and blankets are draped across branches. A basketball hoop has been set up. A surfboard rests outside a tent.

Someone has painted a Canadian flag on a tree trunk. Scavenged car and van seats serve as furniture.

The closer you get to the Disraeli Bridge, encampments begin to resemble villages — red, blue and orange tarps forming compounds enclosed by plywood, Tyvek housing wrap and orange snow fencing.

Were the materials stolen? Donated? Or scavenged from dumpsters and job sites, in states of disrepair too severe for anyone else to use?

Riverside parks reveal the homeless crisis most starkly. Gaboury Park. Goulet Park. North Winnipeg Parkway. Tent after tent after tent.

Near a rail bridge in Point Douglas, a large industrial dumpster sits hollowed out, a yellow tarp stretched across its opening. One person’s trash bin is another person’s home.

At Boyle Street, a blue tarp providing shelter is tucked just below a resident’s backyard, hidden along the embankment. Not far away rise some of Winnipeg’s priciest condos. ‘Open fires not permitted’ signs are affixed to trees short distances away from makeshift fire pits. Tents and tarps are erected metres from ‘No camping’ signs.

Minutes earlier, Pat, 58, shares his story of how he ended up living in a tent near St. John’s Park.

“I had everything,” he says, between puffs on a cigarette.

A Red Seal carpenter by trade, Pat said a lung cancer diagnosis in 2017 followed by heart surgery a year later made working impossible.

He believes he has little choice but to live outside. He doesn’t want to burden his elderly mother, who has little to her name and her own health issues to deal with.

Sometimes it gets lonely, he says, and dangerous, too.

“Do you ever feel afraid out here?” we ask.

“Oh yeah,” he replies.

Main Street hums with commuters heading downtown.

As cars and buses whiz by, two older men rest in a parking lot. One, his beard white as snow, uses a black duffel bag as a pillow. The other, his scruffy beard matted-grey, leans against the graffiti-tagged brick wall.

A few metres away, the doors of OPK — Ogijiita Pimatiswin Kinamatwin — swing open to reveal a different morning ritual.

Nearly 50 volunteers are filling bags with popcorn, sorting muffins and juice boxes and organizing socks, razors, tampons and deodorant into piles.

At the centre is Mitch Bourbonniere, in an orange Every Child Matters shirt. Behind him, the walls are lined with haunting reminders: red dresses and handprints representing the missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls, and the number “215” in reference to the number of unmarked graves found on the former Kamloops Indian Residential School’s grounds.

“Circle up!’ he bellows, and the room falls silent.

Like a quarterback in the huddle, Bourbonniere reminds everyone why they’re there.

“Wherever vulnerable folks gather, they will be preyed upon,” he tells the group.

“For drug trafficking, for sexual exploitation, human trafficking. Recruiting people to do criminal activity.”

A prayer follows, urging everyone to “give us the grace to be able to listen to them. Bless their families.”

At 10 a.m., the group moves north on Main Street greeting every homeless person they encounter and handing out food and supplies to more than 100 people over the next hour.

“Do you have something sweet?” a frail, middle-aged woman asks.

Outside the Bell Hotel, three men in wheelchairs sit together, flanked by two women. An elderly man in Bermuda shorts leans against a building, half-asleep. A younger woman walks past clutching a glass pipe.

Nearby, a distraught woman screams at another, backing into traffic with her arms flailing. OPK volunteers watch closely, ready to protect her from herself.

“This is our little village,” Bourbonniere says of the three-block stretch they patrol. “But what you will see today is spread right across the city.”

Many of the people they meet will later head back to encampments, Bourbonniere notes.

“Wherever vulnerable folks gather, they will be preyed upon.”

“It’s become a culture,” he says. “There are poor souls. There’s a criminal element. And then there’s a third group choosing to live there. For them, there’s a sense of freedom, a sense of community. Shelters can’t give them that.”

Volunteer Mike Kwiatkowski has seen the camps up close. He helps with “Drag the Red” — an initiative that began after the slain remains of Tina Fontaine, a 15-year-old Indigenous girl who was living on the streets, were found in the river in 2014 — and patrols encampments along Henderson Highway and in city parks.

“The big ones are along Main,” he says. “They feel safe there. They have their own space. No rules. If they go to shelters, there are rules. This is their backyard.”

Kwiatkowski tries not to intrude, often scanning with binoculars instead. But danger is always near. Days earlier, he spotted a suspicious tarp bound with duct tape, shaped like a human form. It turned out to be a false alarm.

His reasons to volunteer are personal. His cousin was stabbed to death earlier this summer. That man’s older brother was slain in 2015. And one of Kwiatkowski’s best friends was Cam Downie, who died on the streets of Vancouver in January 2024.

Cam’s father, Scott, now joins Kwiatkowski on these OPK walks every Tuesday and Thursday.

“My wife came out once,” Kwiatkowski says. “But she can’t do it again. Seeing people in a bad way is too hard, knowing that’s how Cam lived.”

A common thread among the volunteers is empathy and lived experience.

Larry Hobson spent much of his adult life in prison for drug-related crimes. Now 60, he works with the community safety patrol. He regularly visits Siloam Mission to see friends still struggling, including his 25-year-old daughter battling her own demons.

“I tell everyone, ‘Hey, you can do this.’ If they can see a guy who was messed up, who did three federal terms, maybe they see hope.”

For Carina Blumgrund, the work is rooted in principle.

“There’s not enough housing,” she says.

“It’s not about solving the problem. It’s about showing love and care and building relationships.”

“Sometimes we just shelter in place and stop caring about others. But if we want to live in a better place for ourselves and others, we should also care about the different ones. It tells you what a community is like when you look at how the most needy are taken care of.”

Beside her walks the youngest volunteer, a 17-year-old who immigrated from Argentina with her family.

“My first walk was very shocking,” says the teen. “For me, it was a whole different world. My friends and I never saw this reality. But it was rewarding. Coming here and giving back is one of the best things you can do.”

She worries about other newcomers, including northern Manitobans displaced by fires, who collide with urban Canada’s harsher realities.

“I feel like there’s a barrier, a wall, between some parts of the city and here,” she says. “But this opens my heart more to people.”

Bourbonniere began these walks during the pandemic, initially to keep people without access to the media or Internet informed. Over time, the walks became something larger, especially as the number of people in need exploded coming out of COVID.

Now, they’re just one piece of a much bigger puzzle that involves government agencies and grassroots groups alike.

“The people in our helping community — it’s 24-7, around the clock, trying to meet the needs of vulnerable Winnipeggers,” Bourbonniere says.

“Helping is medicine. Put a purpose to your pain. We have literally saved lives on this walk. But it’s not about solving the problem. It’s about showing love and care and building relationships.”

For him, it’s also deeply personal. His son, now 40, lives with schizophrenia and has experienced homelessness while battling addiction.

“It’s been 25 years of me trying to protect my son from the misery our relatives face every day. I see my son in all of them out there. I don’t pass by anyone without making sure they’re OK, because I want people to do that for my son when I’m gone.”

Jamil Mahmood believes the growing conversation around homeless encampments — louder and more heated by the day — is largely missing the point.

People who are in encampments are doing so because it’s how they’ve decided is best and safest way to survive extreme poverty, the executive director of Main Street Project says.

“I think making sure that context is provided is always important,” he says.

Main Street, holder of the city’s exclusive contract to lead outreach work with people in encampments in alignment with the province’s Your Way Home strategy, is not without its critics. The organization has been accused of moving too slowly, of enabling social dysfunction and actively contributing to the encampment crisis.

In May, both Mayor Scott Gillingham and Manitoba’s Housing, Addictions and Homelessness Minister Bernadette Smith questioned Main Street’s practices after it was revealed agency workers provided a tent, tarp, suitcases and other supplies and helped to establish a riverbank campsite in Point Douglas — a move they considered contrary to public policy.

“I don’t want to see people in tents. I don’t want to see people living along the riverbank. I don’t want to see people living in parks. I don’t want agencies in any way helping people to do that,” Gillingham said at the time.

Mahmood suggests the reaction was an oversimplification of a complex problem: “Our position has always been these are human beings, there’s nuance to everyone’s situation.

“We’re not happy that there’s encampments. No one is. We want to house everyone that needs housing. It’s very hard, and we’re doing a lot of work because people have very complex needs, and we’re working through that.”

Those root causes are well-known: poverty, trauma, intergenerational impacts of colonization and residential schools, and systemic failures in government institutions. Recent data indicated 70 per cent of people who are homeless were involved with Child and Family Services at one point.

“No one should ever exit CFS or justice or any other system and be homeless. That’s literally a government failure,” he says.

A patchwork of mental-health and addiction services is another barrier.

“There’s wholly inadequate mental-health response, if any. And then you look at addiction — we run the withdrawal management for the city. Even us, we can’t get people into treatment. There’s just not much treatment space,” Mahmood says.

He believes governments squandered a chance to create more permanent housing when federal emergency dollars were available during the pandemic — instead of buying apartment blocks and hotels and building up infrastructure, the organization was renting spaces.

Today, MSP currently operates 44 units at the Bell Hotel, 42 in transitional housing, and a new building that will soon bring their total to 130 units. Their outreach van is another lifeline, connecting with people in encampments and gradually building trust.

Since February, they’ve moved more than 70 people from encampments into permanent housing, with a waitlist much longer.

“We know the public wants to see visible encampments gone. But there’s limited things we can do when there’s no housing available. If we start playing ‘revolving door’ with people, then yes, we’ll have great stats in terms of how many encampments we emptied, but that won’t mean anything, because we’ll have created more encampments in the process.”

Despite some successes, not everything has gone smoothly. Earlier this month, West End residents and businesses complained about drug use, reckless behaviour and litter after people were moved into two supportive housing buildings, with Coun. Cindy Gilroy saying, “we’re taking an encampment and we’re just housing that encampment.”

“I know everyone wants this to be solved quickly, but you can’t just undo years of systemic failure in six months, right?”

Mahmood is not afraid to push back against his detractors.

Other than responding to major incidents, police and firefighters should not be at encampments, he says, only community-outreach and mental-health support workers. And the city’s new policy to eliminate places where homeless people can set up shelter will only exacerbate the problem, pushing them further into unsafe locations.

“They’re forced to move to a place where outreach doesn’t know where they are, or they don’t have any connections to the community,” he says, describing the proposed policy as symbolic, which fails to address the acute mental-health and addictions needs of inidividuals.

Mahmood believes Winnipeg can eradicate homelessness — but only with sustained investment and public will.

Until then, he and his team will continue to work to address immediate needs and pursue long-term solutions.

“We do think there’s a need for a broader public awareness and education around homelessness encampments. That’s where I think we’ll start to see societal change,” he says.

“I know everyone wants this to be solved quickly, but you can’t just undo years of systemic failure in six months, right?”

It looks like a garbage truck exploded.

Days after being released from jail for serving time for a variety of offences, Jessie Winberg put down stakes on a patch of riverbank dirt.

With no release plan in place, he initially went to a shelter but left after he says he was jumped and robbed of a necklace.

“Quiet. Lonely. Nice, I guess, to be outdoors,” the 38-year-old says, standing near a pile of empty Rice Krispies and Frosted Flakes boxes, crushed pop and beer cans, food wrappers and liquor bottles.

He doesn’t flinch as wasps swarm around him.

Winberg says he doesn’t want any more trouble after a life filled with it. The scar on his head? Caused by a bullet years ago when he was running with the Manitoba Warriors.

The less-visible scar near his temple? Caused by a baseball bat, which left him with permanent brain damage and frequent memory loss, he says.

His work history is spotty — a bit of roofing and construction. He doesn’t have a penny to his name. He mentions a son, now about eight, who lives with his mother in rural Manitoba.

“I know I can’t have kids here,” he says.

Winberg wanders downtown during the day, finding food at shelters before returning to sleep on a dirty mattress. A broken-up box serves as a headboard; a blue tarp as a door.

Across the river is a clear view of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights, with the gleaming Tower of Hope reflected in rippling water below.

Does he ever feel sorry for himself?

“Sometimes.”

But he adds, “it’s the hand you’re dealt.”

mike.mcintyre@freepress.mb.ca

X and Bluesky: @mikemcintyrewpg

Mike McIntyre is a sports reporter whose primary role is covering the Winnipeg Jets. After graduating from the Creative Communications program at Red River College in 1995, he spent two years gaining experience at the Winnipeg Sun before joining the Free Press in 1997, where he served on the crime and justice beat until 2016. Read more about Mike.

Every piece of reporting Mike produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, September 26, 2025 6:33 AM CDT: Corrects photo cutlines

Updated on Friday, September 26, 2025 11:49 AM CDT: Updates graphic