Expressions of remembrance Our monuments, statues and memorials give form to honouring, grieving lives lost in war

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Tucked at the end of a walkway, which dead-ends between the University Centre and the Helen Glass Centre for Nursing on the University of Manitoba campus, stands a monument in memory of students who never returned from the First World War.

Carved from local Tyndall stone and at just over a metre high, it commemorates the 30 medical students, from both the Manitoba Agricultural College, which later became part of the University of Manitoba, and other universities across the western provinces, who were killed while serving with the 11th Canadian Field Ambulance.

It’s just one of several monuments at the university marking student sacrifices during the First World War and one of many markers — from cenotaphs to statues and even lakes — across the province commemorating Manitobans who have served in conflicts since the province was created in 1870.

Many of those monuments are either hidden or in hard-to-find places. Even veterans from the Second World War — who not so long ago were part of marching parades and outdoor services marking Remembrance Day — are mostly tucked away living the remaining days of their lives in personal care homes.

Out of sight, overlooked and often underappreciated — casualties to the passages of time.

Back at U of M, there is a red-coloured Red Cross emblem on one side of the Field Ambulance memorial; on the other three are the names of the students who died while helping the wounded through various engagements including the Battle of the Somme and Battle of Vimy Ridge.

Its formal unveiling took place in October 1927, near two other First World War monuments, the Avenue of Elms and the Manitoba Agricultural College War Memorial. The monument was moved to its present location in 1950 to make way for the construction of an engineering building.

“No one sees it there,” said Wayne Chan, a research computer analyst with the university’s Centre for Earth Observation Science and, in his spare time, an amateur historian. He wrote an article about the monument for a university publication.

“Last year, I was creating a scavenger hunt for a homecoming and this monument was one of the questions,” Chan said. “It turned out to be one of the hardest questions, even though some of the participants had been on campus for 15 years or more. They even asked nursing students and they didn’t even know about it — and their building is next to it.”

Other monuments at the university’s Fort Garry and Bannatyne campuses are in more prominent places. The Avenue of Elms lines Chancellor Matheson Road. The Agricultural memorial is in the middle of the boulevard at Chancellor Matheson Road and University Crescent. The Manitoba Agricultural College Roll of Honour is displayed near an entrance to what is now the university’s Administration Building. Long tablets, located on either side of the doors to the medical college, list the graduates and students of the school who died during the First World War — as well as during the Boer War and North-West Rebellion.

Ninety-eight years after the Field Ambulance monument was formally unveiled, it is looking a bit worse for wear. A sundial disappeared years ago (since replaced with a commemorative plaque) and the etched names are fading.

Warren Otto, the military support officer at the university, said he has wanted to have the monument restored for the last decade.

“I’ve been hoping to get some interest in it,” Otto said, noting he is in talks with possible donors, but that nothing is confirmed. “It is coming up to the 100th anniversary of its unveiling.”

Chan said while it makes sense for the monument to be situated next to the building training tomorrow’s nurses, he believes it should be moved to a more prominent spot.

“There are a few picnic tables where it is at, but it is not in a place where you walk by it and see it,” he said. “I don’t know where it could be, but it should be in a more prominent place.”

At ages 102 and 101 respectively, Percy Rosamond and Andrew Prodanuk are among select — and rapidly dwindling — company, serving as living monuments to Canada’s sacrifices in the Second World War.

Veterans Affairs Canada says that of the 1.159 million Canadians who served in the war, with about 42,000 killed and 55,000 wounded, only 4,769 men and 880 women are still alive. Their average age is 100.

Both men reside at Deer Lodge Centre, a facility first created to help veterans of the First World War live out the rest of their lives.

Rosamond, born and raised in Toronto, enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force right after turning 19 in 1942. He trained to serve as an air-frame mechanic, working to keep planes in the air, and was soon shipped to England.

“I chose the air force,” he said recently, sitting in his wheelchair, his voice still strong. “I didn’t want to go to the army. I don’t know how I became a mechanic. I just joined and they said I would be a mechanic.”

Rosamond had a special reason for enlisting as soon as he could. Although he was born in Canada, his parents and older sister immigrated from England to Canada in 1912. His sister was injured in the Halifax Explosion in 1917, which involved the collision of two cargo ships, including one loaded with munitions bound for Europe.

He was stationed at RAF Tempsford, located just north of London, where he worked on Liberator bombers. The base was noted for dropping secret agents into occupied Europe. An older brother also enlisted, serving as an air gunner on bombers and was stationed in England.

“He flew home the day I arrived. He had been on 25 missions.” Rosamond said.

Because of the grim toll taken on bomber crews — almost three-quarters never made it back from flying on missions over Fortress Europe — both Canada and the United States rotated crews back home if they survived 25 missions.

Loud noises associated with his job — and not having ear protection — left him deaf in one ear.

After the war, Rosamond returned to Ontario where he married Eileen. They were married for 55 years. He was hired by Ontario Hydro as a machinist, but he enlisted in the Canadian Army after getting laid off.

“Jobs were scarce at the time so I joined the army. I couldn’t get back into the air force because I was deaf in one ear.”

Rosamond serviced army helicopters and is how he ended up in Manitoba — he retired while working at CFB Rivers.

Prodanuk downplays his war involvement. He was training as a navigator when his service was no longer needed — the war was coming to a close.

“My experience in the Second World War was minimal,” he said recently.

“When you reached the age of 19 years, you were expected to join the service. I tried to be a pilot, but it was towards the end of the war so I completed a navigator’s course. But, before you knew it, they said there was no need and I was discharged and sent home.

“But I was ready to serve.”

Prodanuk trained in Brandon, Regina and Saskatoon, with a final stop also in Rivers.

“I didn’t like the navy — I didn’t like water — and I didn’t want to be in the army,” he said.

“War is war. The chance of getting killed is always there.”

Back in civilian life, he stripped car engines before working for a company that rebuilt engines used in mines. He was married 70 years — he said his vows while still in uniform — and went on to have two sons and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

“I’ve had a good life,” he said.

“War is war. The chance of getting killed is always there.”

Michael Petrou, historian, veterans’ experience, at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, said it will be “a tragic loss” when the last Canadian veteran of the Second World War dies.

“I think we lose something very special and irreplaceable,” Petrou said.

“We are losing an irreplaceable living link to one of the most consequential events of the 20th century, if not the last 1,000 years. It’s not just their own experience, in combat and in war, but 80 years later in Canada, we live in a country that, in many ways, was shaped by the Second World War.”

Petrou said the role of women and some minority communities changed, Indigenous veterans, who were treated as equal comrades in the war, pushed for equal treatment here through subsequent years, and veterans, who might never be able to afford it, were offered chances to get education and housing they never would have received before the war.

“We are still living in a country where the echoes of the Second World War are reverberating in ways we might not appreciate,” Petrou said.

“When we lose the veterans, we lose our last direct and living connection to the events which set all that in motion.”

From their failing hands, there are still many Manitobans who have made it their mission to ensure the contributions by the Greatest Generation are not forgotten by future generations.

About a 15-minute drive west of Morden is Darlingford where a memorial to area residents who served in the two world wars has stood for more than a century.

Darlingford Memorial Park, born in tragedy, is the only free-standing building in Manitoba solely dedicated to commemorating the war dead.

Ferris Bolton, a local farmer who was also a businessman and politician, lost three of his sons in the First World War, during a three-month span in 1917.

Bolton decided to honour his sons, and the residents who served with them, by donating land for a memorial park. It opened just four years after the three died.

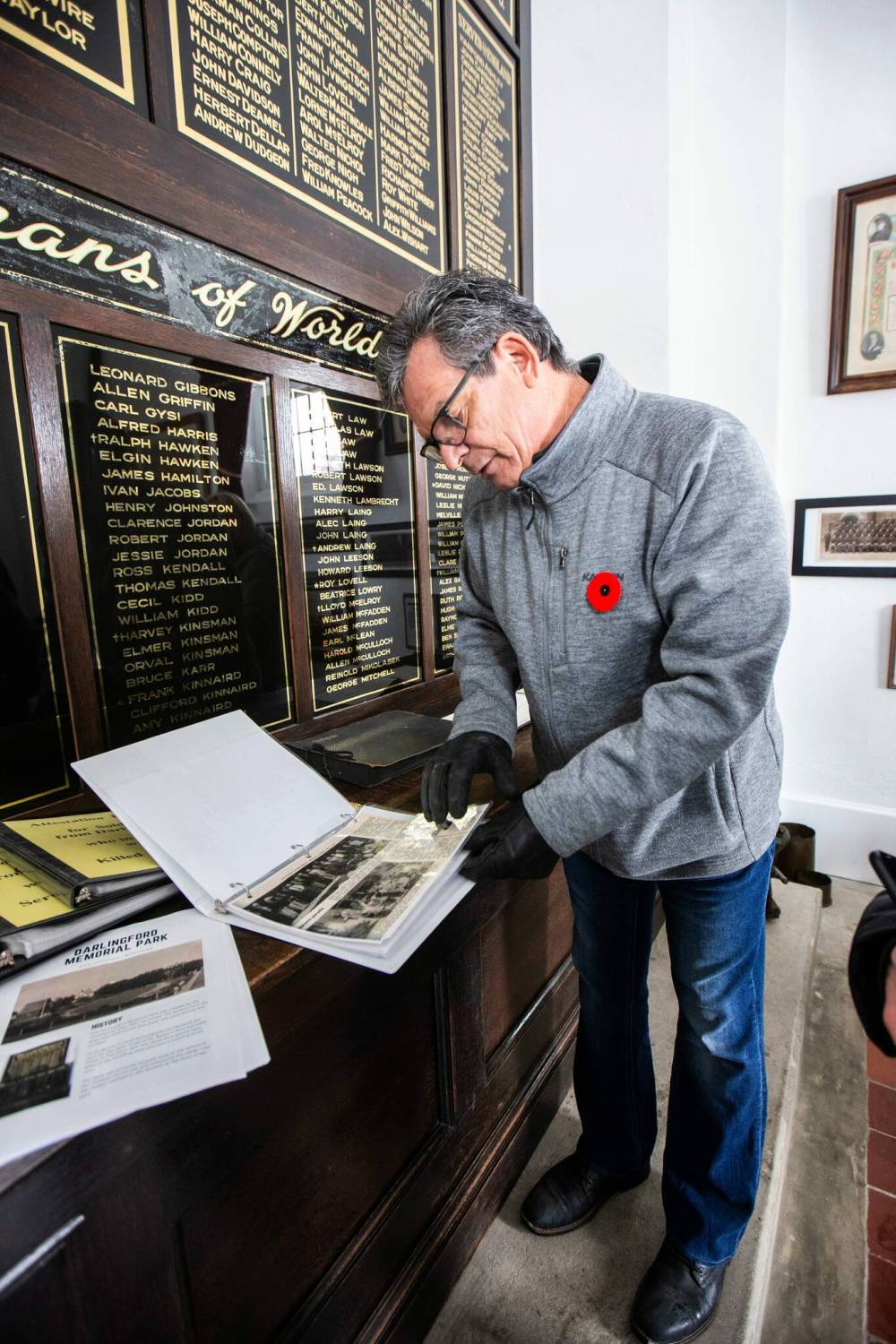

The park features evergreen trees, flower gardens, a pathway and a brick memorial chapel. Inside are inscribed the names of the area residents who served in both world wars. For a town and area community of only about 200 residents even today, the wars’ cost was immense — 20 died in the first war and 12 in the second.

Brian McElroy, the longtime chair of the park committee, said the memorial is showing its age. While the roof is fine — it was re-shingled some years ago — some of the evergreen trees which reached the end of their life span were removed and turned into bark chips for a new pathway.

But McElroy said the other work needed is more intricate.

“Some of that gold lettering needs to be replaced,” he said. “We’re in the process of figuring out how to do that — it is a (provincial) historic site. If you know anyone who knows how to do this, it would be nice to hear from them. We need to match the gold lettering.”

Back in Winnipeg, veterans, members and guests socialize on the main floor of Norwood St. Boniface Legion No. 43.

But on the second floor, open on Saturday afternoons, is the Legion House Museum, operated by the Military History Society of Manitoba. It offers exhibits ranging from troops in the 1840s serving in Lower Fort Garry through to today.

The society’s Bruce Tascona says one of its more poignant exhibits features the uniform of Cpl. James Arnal, who was killed in action in Afghanistan, and the uniform of his mother’s, who worked at the Tim Hortons at the base after his death.

Arnal, 25, was killed when a roadside bomb went off on July 18, 2008. Two years later, his mother, Wendy Hayward, decided to retire and work for a time at the Tims and other Canadian stores at the Kandahar Airfield.

“When you look at all the uniforms we have, most of them were in closets and we get them 100 years later,” Tascona said. “Cpl. Arnal’s is the only one which came from the front. We proudly display it. And his mother, who has since passed away, donated her uniform too. She found working there therapeutic.

“When you want to talk about loss, this is it.”

Few Winnipeg schools can match students’ commitment to bear arms than Daniel McIntyre Collegiate Institute. The current iteration of the school, now 102 years old, proudly features a memorial alcove listing the names of the 2,425 students who answered the call to war. Many of them never returned.

Besides the scrolls and bronze plaques, the alcove also features a stained-glass window created by acclaimed Manitoba artist Leo Mol. It and the alcove were restored in 2013, thanks to funding from alumni and federal Veterans Affairs, in time for the school’s 100th anniversary.

Alumnus Lila Larson was there when the alcove opened.

“There’s a long history of what the school has done to create leaders and this is part of it,” said Larson, 82, a member of the Class of 1961. “That alcove is so important. It connects a lot of students with their grandparents and great-grandparents.”

Student council co-presidents Juliana Chan and Jamie Soriano, both currently in Grade 12 and 17 years of age, said they think of the former students every time they walk past the alcove.

“I think about if it was my peers going into the war. I can imagine what their families would be going through,” Chan said.

Soriano said it makes her think about if the male students in her class, as well as her older and younger brothers, had been born a few decades earlier.

“I can’t imagine what they went through,” she said.

One of Winnipeg’s most visible monuments to the war dead has been missing in action.

The statue of the First World War soldier, which stood sentry outside the downtown Bank of Montreal for more than a century, was removed earlier this year to make way for opening Portage and Main to pedestrian traffic.

It will come out of storage and be back in the public realm next spring when it will be re-erected to stand watch among veteran’s tomebstones at Brookside Cemetery.

The Manitoba Métis Federation purchased the historic bank building in 2020 and the statue, erected in 1923 and dedicated to bank employees who served in the Great War, came with the sale.

David Chartrand, MMF president, said he is hoping the new concrete base for the statue will be poured before snow falls so the official ceremony can be held on April 9 — the 109th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. The costs will be shared by the MMF and the Bank of Montreal.

“It’s definitely going to be in a place where it should be,” Chartrand said.

“When we bought the real estate, I could have easily said to the Bank of Montreal, ‘Take your statue out of here.’ But because of my passion to respect veterans at all costs … I’m still responsible for it. So that’s why we’re still leading it.

“We will honour it properly and we are going to take care of it.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is a general assignment reporter at the Free Press. He graduated from Western University with a Masters of Journalism in 1985 and worked at the Winnipeg Sun until 1988, when he joined the Free Press. He has served as the Free Press’s city hall and law courts reporter and has won several awards, including a National Newspaper Award. Read more about Kevin.

Every piece of reporting Kevin produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.