Undaunted defiance amid raw remembrance

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

In the heart of Kyiv, perched on a hilltop beside a ravine, there stands the remains of a 17th-century fortress. Built to defend the city from invasion, it was rebuilt and repurposed over the years, and now houses a massive military hospital complex; in normal times, it’s also a tourist site with a small museum.

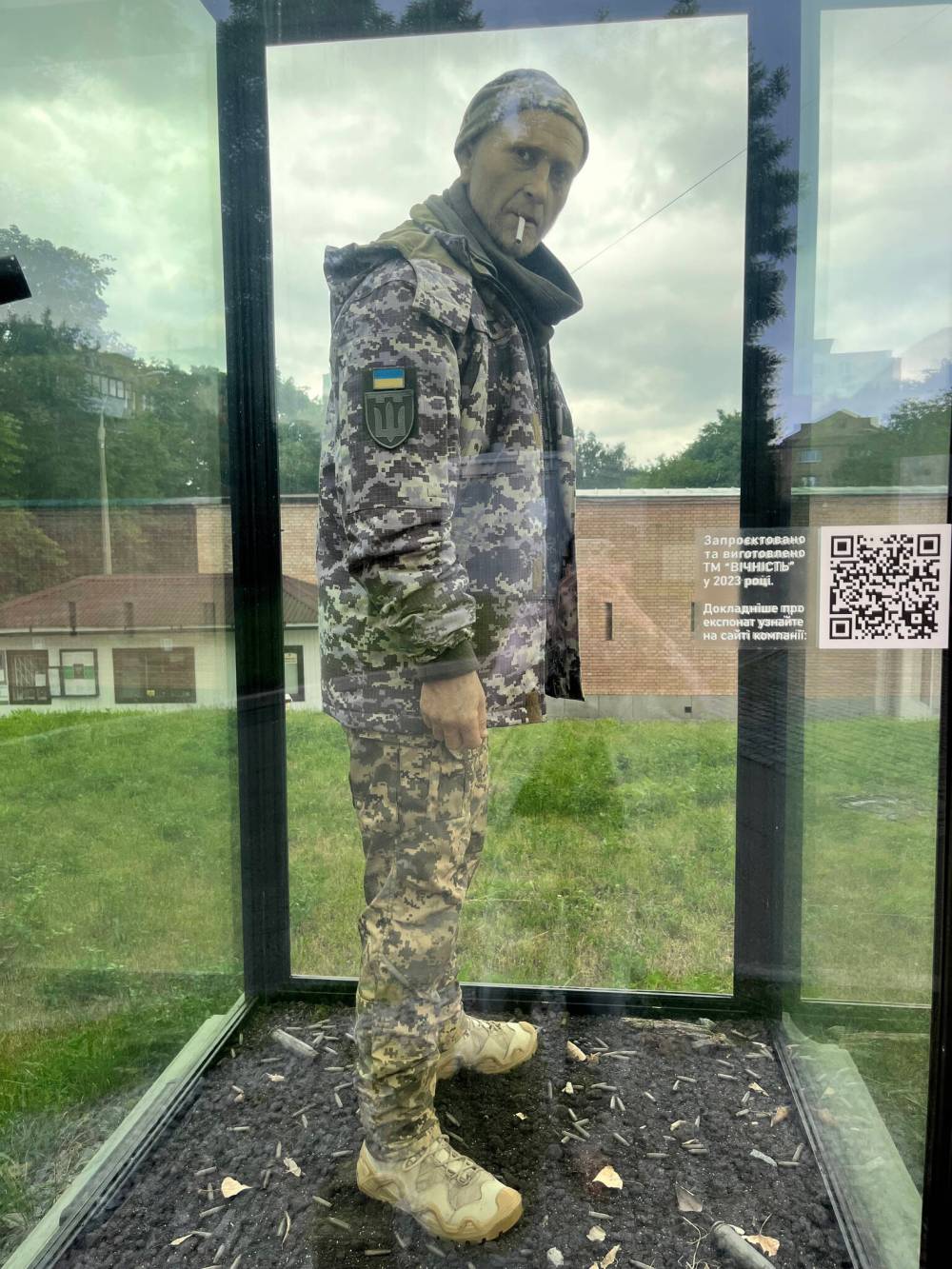

At the edge of that complex, on a patch of unkempt grass just past a guarded gate, a soldier stands in a plastic box. He looks at you, but does not move. Does not breathe. There is no breath in him.

When I visited the fortress this summer, I knew he was somewhere on the complex. Yet still I jolted with a start when I first saw him, an apology on the tip of my tongue for being in his way, until I realized what he was, and that he would not answer.

I had seen this man before.

In March 2023, a 12-second video surfaced on Telegram, evidently posted by Russian fighters. It shows a Ukrainian soldier, unarmed, standing in a shallow trench. His hands hang empty beside him; a cigarette dangles from his lips. He gazes at his captors a bit sidelong, over his right shoulder, without any hint of a flinch.

The Russian troops ask the man a question. He takes the cigarette in his fingers and exhales a waft of smoke.

“Slava Ukraini,” he says, “glory to Ukraine,” and then the Russian rifles chatter and he falls to the ground dead.

Behind the camera, one of his killers hisses at the corpse, in Russian: “Die, bitch.”

The casual cruelty of the execution, the pride apparent in making and sharing the video, juxtaposed with the man’s quietly defiant last words: these shattered Ukrainians’ hearts, made the then-unknown man a hero and, for just a brief window of time, grabbed global headlines and shocked the world.

Within days, Ukrainian authorities confirmed the slain soldier’s identity. An electrician, 42-year-old Oleksandr Ihorovych Matsievskyi had signed up to fight at the outset of the full-scale Russian invasion. He disappeared near the then-besieged city of Bakhmut in December 2022; his bullet wound-riddled body was traded back the next month.

Until the video surfaced, only his family and brothers-in-arms mourned him. After, Matsievskyi’s image was seared into the public consciousness, adapted into street art, murals, patriotic merchandise. Ukrainian boxing legend Oleksandr Usyk wore a shirt emblazoned with Matsievskyi at a 2024 weigh-in; a Georgian sculptor cast his figure in bronze.

Then there is the monument of Matsievskyi in front of the Kyiv Fortress, the one in the plastic box.

The sculpture, created by artists Oleh Tsos and Albina Safronova and unveiled in late 2023 with Matsievskyi’s mother and wife in attendance, is uncanny. Made of silicone and plastic, designed with the aid of digital scans, it is not just lifelike but deeply unsettling in its realism; it captures him as he was in the last 12 seconds of his life, exactly.

The cigarette perched between his lips; the delicate blue threads of his veins; the war-weary folds of his face. His expression: exhausted, resigned to his fate, though not defeated. Even the ground under the sculpture’s feet isn’t the raggedy green grass of the Kyiv Fortress, but the leaf-strewn dirt of the forest where Matsievskyi was executed.

MELISSA MARTIN / FREE PRESS A statue of Ukrainian soldier Oleksandr Matsievksyi, capturing the last 12 seconds of his life, stands on the grounds of the Kyiv Fortress. Matsievskyi was executed on camera by Russian soldiers in December 2022, with the video later posted on social media.

The verisimilitude is eerie. When you walk past the sculpture its eyes seem to follow you, gazing unblinking into your own. When I visited, I could not look at it — at him? — for long, discomfited by the sense of falling into a valley between life and not-life.

I could not shake the sense those eyes were telling me something.

Memorials to the fallen are not often like this. It’s too close for comfort, too literal, too graphic. More often, public memory selects more noble depictions: photos of proud men in clean uniforms. Marble and granite. Stately cenotaphs inscribed with names, dates and reverent phrases: To Our Glorious Dead.

In Winnipeg, there are many such monuments. In the years since the 20th century’s two most cataclysmic wars, our notice of them has faded. We walk past them, drive past them, while their forms blend into the visual noise of the city; only once a year, on Remembrance Day, are we called to pause and consider them as something more.

Let’s be honest: most of us do not go to those ceremonies. Life is busy, and those biggest wars were a long time ago.

What do we remember, when we remember? What do we forget, when we don’t? How do we pierce through the fog of time and reconnect with the fallen, so we can renew the lessons we need to learn from their deaths?

What do we remember, when we remember? What do we forget, when we don’t? How do we pierce through the fog of time and reconnect with the fallen, so we can renew the lessons we need to learn from their deaths?

That’s when I understood what the sculpture’s eyes were saying.

In the sculpture’s fidelity to life, the creators were offering not just a tribute to Matsievskyi’s quiet act of bravery but a much more challenging statement. The figure’s gaze, seized from the moment of a final breath and lifted out of the reach of death, demands that we see him not first as a hero, but simply as a man.

Just a man. An electrician from Nizhyn, near Kyiv, with tired eyes and a slightly bowed head. A man who could have lived — should have lived — an anonymous life in peace.

A man who was not, when he lived, any larger than life, but simply went to defend his country and died what, but for that video, would have been an unknown and invisible death.

His last words, he spoke only for himself. He could not have known the world would see them.

And through his frozen gaze, preserved precisely and forever, the viewer is required to see not only that humanity, but also to confront the circumstances that propelled it from average life to heroic legend. It’s a gaze that stands as a condemnation of a collective global failure to action: of lessons not learned, promises not kept, professed values not honoured.

The monument should not stand in Kyiv, I thought. It should be toured in front of every parliament in Europe; it should be placed in front of the United Nations and the International Criminal Court. It should be turned to face every international body that allowed the travesty of the Russian invasion to grind over Ukraine without adequate cost.

Let that gaze find the world’s power brokers where they shelter, casting its silent and unblinking reproach.

Let that gaze find the world’s power brokers where they shelter, casting its silent and unblinking reproach.

And on Tuesday, when Canada pauses to honour those who fought and perished in wars of the past, when we lay wreaths and adjust poppies and hear the cannon blasts, let us try to think of our fallen like this. Not only names, not only dignified photos and polished inscriptions.

They were just men, just women. Just people, their lives among millions of threads snipped by the grinding force of history and war, but still woven into the same tapestry as our own.

They did not go to their rest knowing what their sacrifice meant; they did not live to see how their chapter of history would end.

And if we could have seen their eyes in their last moments, what would those eyes have said?

We will never know for certain. But for the memory of those of the past, and for our hope in those who will come after, we must at least try to imagine.

There may never come a day when there are no wars to snip living threads. But lest we forget the dream that it will, let us remember those to whom it happened.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.