AI’s clichéd creativity

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/08/2024 (472 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

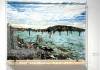

WHAT IT IS: This is a mountain landscape generated by Adobe Firefly with text-to-image prompts. Using pixels instead of paint, machine algorithms instead of purely human imagination, it’s an example of the AI-created imagery increasingly infiltrating our visual universe.

WHAT IT’S ABOUT: AI-generated images are often deployed in divisive and destructive ways. Within our polarized political discourse, pictures can be cooked up to dehumanize opponents and elevate cult leaders. AI-generated content can be used for deepfakes, frauds and misinformation.

But even when AI images are neutral and anodyne — who doesn’t like a majestic mountain scene? — they are almost always kitschy and clichéd.

AI generated art.

A recent article in The Atlantic by Caroline Mimbs Nyce explores the relentless sameness of AI images. There’s a certain “look,” Nyce points out, that persists not just within a particular image-generating model but across the different programs offered by the big tech companies. This comes down primarily to the parameters of the technology, which include the banks of images the models work from and the way these images are evaluated and matched with verbal cues.

This means that even though DALL-E, Midjourney, Stable Diffusion and Adobe Firefly can generate literally billions of possibilities, their images tend to default to a distinctive esthetic, which is usually gleamy, shiny, generic and photorealistic. (Or, practically photorealistic. You have to overlook AI’s persistent issues with fingers — how many fingers most people have, where they put them, how they use them to hold things.)

It feels as if there’s some room for the human touch in the text prompts. Adobe Firefly, for instance, allows for a lot of tinkering, and I chose some options to make my alpine image more painterly and textured.

You can specify artistic movements (art deco, pop, constructivism, medieval). You can pick mediums and techniques (acrylic paint, black-and-white photography, comic-book mode). You can noodle around with colour, tone, lighting and viewpoint. But even with all these choices, the results keep trying to head back to where AI feels most comfortable.

AI is very keen on the “golden hour,” for example, that time just after sunrise or before sunset when the sun is low and the ground feels suffused with soft, warm light. With Adobe, you can request a “Golden Hour” option, but even when you don’t, there’s a good chance you’re going to get it, as in this mountain scene, with its lowering, molten sun glowing dramatically through the clouds.

And speaking of clouds, wow, AI just adores clouds — big, diagonal, dramatic, roiling banks of clouds. Experimenting with various landscape painting formats, I found that even when I used the prompt “no clouds” or “cloudless sky,” the AI gremlins couldn’t help themselves. Possessing an absolute horror of empty space, they just had to insert some wisps of white cirrus cloud to break up all that blue.

When it comes to composition, AI favours “the rule of three.” This picture breaks into a distinct foreground, middle ground and background, each taking up roughly one-third of the picture plane. AI is also hepped on certain aspects of colour theory: It clearly knows that blues and oranges are complementary colours that really pop when placed near each other, and whenever it can, it will run with that combo, as it does here.

WHY IT MATTERS: It’s not fair to set up a binary model where AI is defined as purely derivative and human creativity as purely original.

Western art history has traditionally made way too much of the myth of the tortured, heroic genius working in splendid isolation. In fact, human artists, like AI, have always drawn on images from other places. They’ve stolen from one other, borrowed from other cultures, rummaged through the past, looted popular culture.

But while artistic expression may involve remixing, the best works put together old images in a new way, making something that is touched by the variations of the human hand and the idiosyncrasies of the human mind.

With a system based only on precedent and rules, AI’s first impulses are conventional, and they usually end up getting stuck there. Mountains are magnificent, rivers are gently winding, trees are autumnal. Public buildings are neoclassical, people are blandly beautiful. Everything comes down to lowest-common-denominator visual clichés.

This mountain landscape isn’t ghastly, exactly — it’s nowhere near as bad as my “sad man drinking absinthe in a 19th-century Paris café,” which was the stuff of nightmares. But it doesn’t say anything fresh or interesting, about mountains or about image-making. For now, at least, art still needs human beings.

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.