But at what cost?

Artwork explores dark legacy of resource extraction

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/10/2024 (429 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

WHAT IT IS:

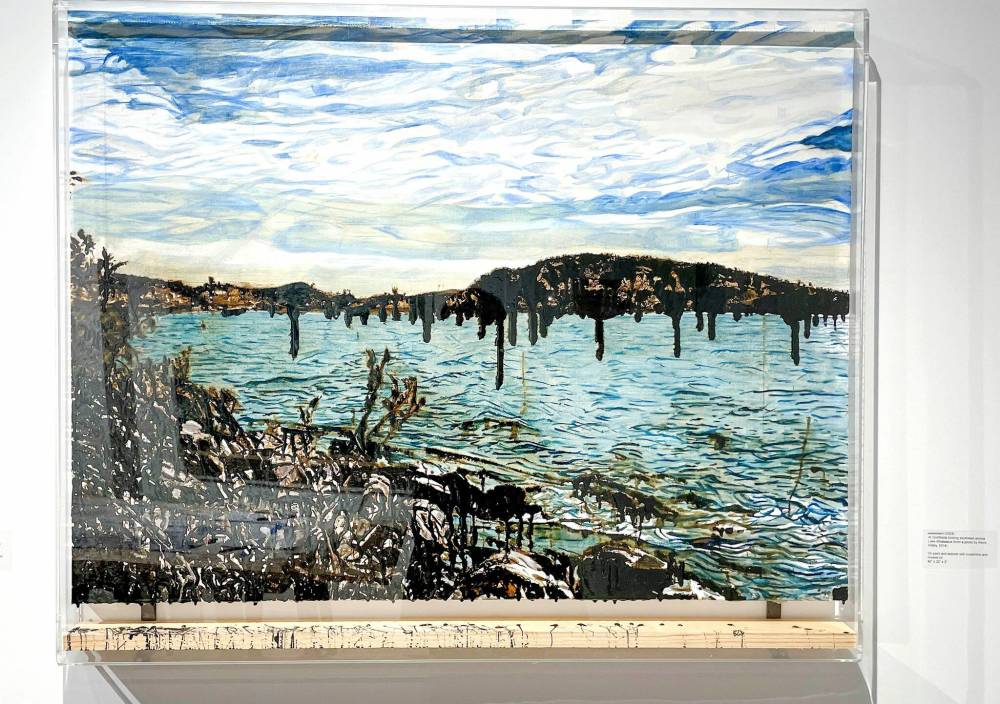

Part of an exhibition of mixed-media works on view at aceart until Oct. 18, extracted I by Brandon-based artist Ben Davis, examines the human and environmental costs of intense resource-extraction operations.

WHAT IT’S ABOUT:

Building on an initial collaboration with Kevin Walby, a professor of criminal justice at the University of Winnipeg, Davis has undertaken a years-long research project looking at a decommissioned mining site near Uranium City, a community just south of the border between Saskatchewan and the Northwest Territories, on the traditional territory of the Chipewyan Dene people.

Having gathered information that includes photographs, documents, satellite maps and audio interviews, Davis analyzes, interprets and expresses that data through art.

Davis’s show extracted I might initially suggest a connection to the works of Tom Thomson and members of the Group of Seven, who used paintings of the Canadian landscape to build up a mythology of rugged, untouched wilderness. But Davis’s work suggests deeper and darker currents running under these seemingly pristine images. He deliberately unsettles the surfaces of the traditional landscape genre, encouraging viewers to unpack the tricky historical, social and ethical dimensions of the relationship between humans and the natural world.

Working from a photograph looking southeast across Lake Athabasca, Davis starts with trees, hills, water and sky. There’s a restful blue beauty in these familiar elements, but the strong dark lines that pick out nearby branches and a distant shoreline start to ooze over the water, disrupting the visual illusion of the picture plane and suggesting contamination and threat.

Davis is working here with asphalt (derived from bitumen, which is produced from crude oil). Its inky blackness accrues and drips down, caught on a wooden plank at the bottom of the image. The asphalt will eventually eat into the painting, a gradual process that underlines the harms that can remain even after a large-scale mining operation has shut down.

There are several components to Davis’s work, including satellite images of the mines and the surrounding areas, which can be traced over in pen by visitors to the show in a meditative, interactive process. Another grouping involves block prints of a landscape scene, which repeat and repeat until the image gradually fades into white.

Transmuting raw information into quiet but resonant artworks, Davis suggests layers of what lingers and what is lost in the wake of resource extraction.

What often lingers, as extracted I makes clear, is toxic contamination in soil, water and air, which can impact traditional ways of living that predated the resource boom, such as farming, fishing and hunting.

What is often lost is connection. Extraction operations can disrupt existing communities. They can build up sudden towns and settlements, but once the mines are tapped out or the oil runs dry, many of these once populated and prosperous places are slowly abandoned. The exhibition includes audio interviews with remaining residents of Uranium City, their memories building up another layered picture of people and land.

WHY IT MATTERS:

As Canadians, we are facing questions about environmental damage and unchecked industrial expansion. We are grappling with issues of the spoliation of Indigenous lands. extracted I, with its familiar landscape made subtly disturbing, urges us to think more deeply about what we’re really seeing.

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.