A dream 60 years in the making Qaumajuq's roots date back to 1957 and a collection bought at the Bay

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/03/2021 (1709 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Any collection, even the world’s largest collection of Inuit art, has to start somewhere.

It was 1957 when the Winnipeg Art Gallery acquired its first artwork made by an Inuit. It’s called Mother Sewing Kamik, and the 33-centimetre-tall stone and ivory piece was sculpted by Pinnie (Benjamin) Naktialuk of Inukjuak, Que., a village on the eastern shore of Hudson Bay.

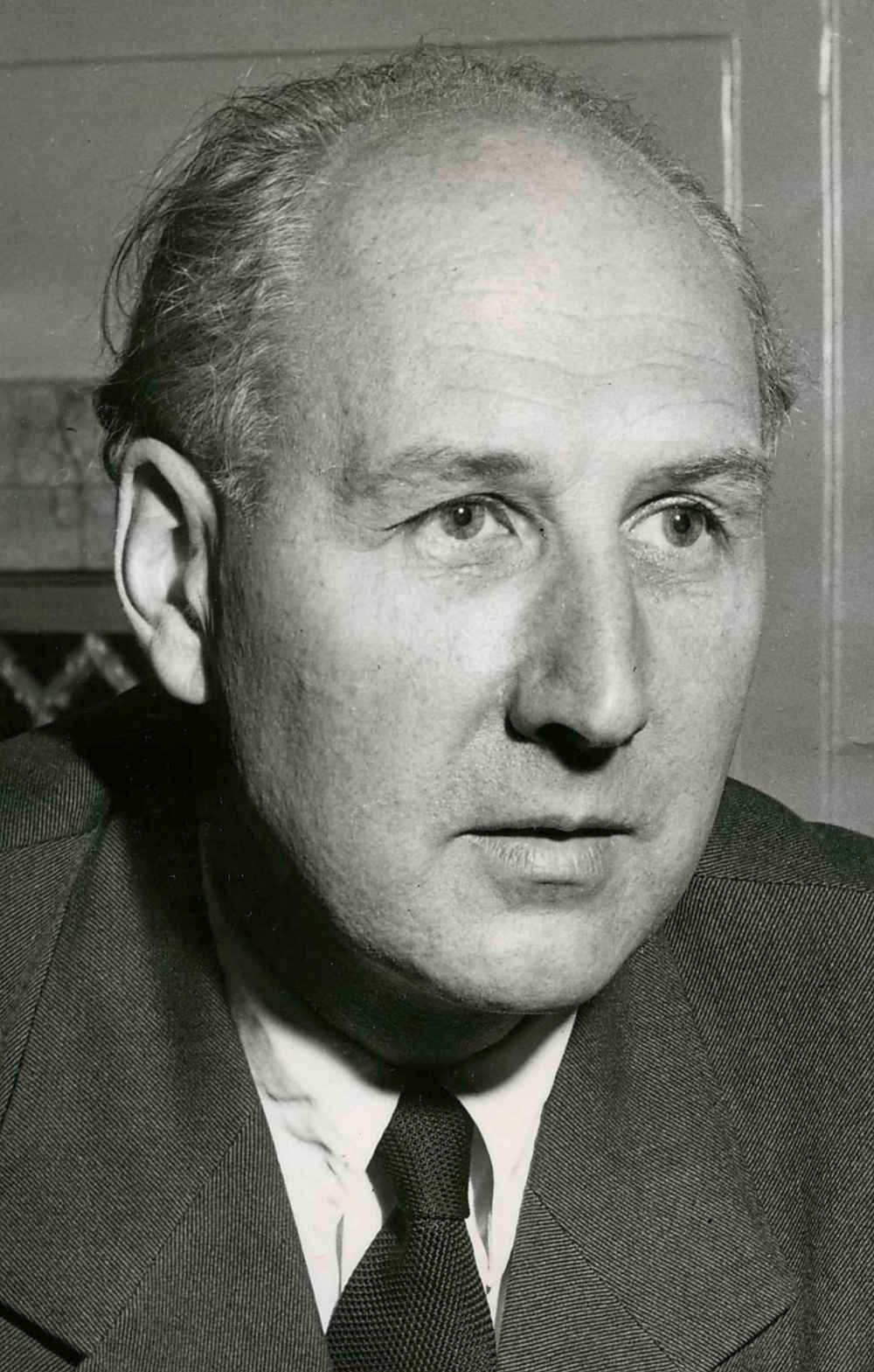

Two years earlier, the sculpture caught the eye of Ferdinand Eckhardt, who was the WAG’s director from 1953 to 1974. It was among several Inuit sculptures on sale at the Bay’s downtown store in Winnipeg, just down the street from the WAG’s old home at the Civic Auditorium.

Eckhardt convinced the gallery’s Women’s Committee to raise funds and buy it, says Nicole Fletcher, who is the gallery’s collections co-ordinator.

In the book Journey North: The Inuit Art Centre Project, which the WAG is releasing along with Qaumajuq’s opening, Stephen Borys, the gallery’s current director and chief executive officer, writes that Mother Sewing Kamik was purchased, along with some other soapstone carvings from the Bay, for $85.

But the WAG didn’t accumulate close to 14,000 works by about 2,000 Inuit artists from across the Arctic by saving up for Bay Days.

Not long after the purchase, Eckhardt declared Inuit art would be one of the WAG’s priorities, and in 1960 the gallery began buying prints from artists from Kinngait (formerly Cape Dorset), Nunavut, and later the gallery purchased 139 Inuit-made works from George Swinton, who was with the University of Manitoba’s School of Art and had also taken an interest in Inuit artists and their work.

Much of the WAG’s collection of Inuit art has also been accumulated from donations by individual collectors and organizations. A donation of 4,000 works of art in 1971 put the gallery, and Winnipeg, on the Inuit art map.

“The collector was Jerry Twomey, his family (owned) T&T Seeds here in Winnipeg,” Darlene Coward Wight, the WAG’s curator for Inuit art, says.

“He’s a geneticist. He decided he was going to retire to California and breed roses full time, so his 4,000 pieces he had amassed over the ’50s and ’60s came to the gallery.”

Coward Wight will mark her 35th year at the WAG in May and during that time she has curated 95 Inuit art exhibitions and made many trips across the Arctic to visit artists and view their work.

She began learning about Inuit art, the artists who make them and life in the North in 1982 when she landed a job with Canadian Arctic Producers, the marketing arm of artist co-operatives in Nunavut, the Northwest Territories and Yukon. Whale-bone carvings from artists in the high Arctic caught her attention.

“Because the work was often shamanic in subject matter — that area was quite remote at that time, and there hadn’t been a whole lot of acculturation in terms of religion — they were still close to their shamanic beliefs, which was in the art. I was just fascinated by that,” Coward Wight says. “I really loved the very expressionistic style.”

That first journey was to what is now Taloyoak, Nunavut, one of Canada’s most northern communities, about 2,200 kilometres north of Winnipeg. She borrowed a parka and boarded a DC-3, a Second World War-vintage plane that carried freight and passengers, to visit the talented artists.

“It took two days to get there and I was sitting on the plane next to freight because freight was the most important thing to the North,” she says. “There was one other person on the plane. He was from Spence Bay (the name for Taloyoak until 1992) and he was pointing out muskox on the ground and he said he could see them by their breath. I’ll always remember that.”

As the WAG’s collection grew, its board of directors had to figure out how and where to display the works because only the ones chosen for exhibitions have been seen by the general public. The rest have remained stored in the WAG’s basement vault.

Coward Wight remembers discussions beginning back in 1986 about how to show off the collection. She said studies were even launched to find a solution.

Hopes for a dedicated space for the collection began to take a positive turn in June 2008 when the board hired Borys, who grew up in Winnipeg and was the chief curator of the John and Marie Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Fla., as the gallery’s director and CEO.

“Over the years there’s been talks about doing that and it always ended up going away,” Coward Wight says. “(A new building) just seemed to be too good to be true, but there was a real commitment, and the board, when they hired Stephen, it was to get this done, and he was very excited by the idea of a building because he has an interest in architecture.

In 2012, Los Angeles architect Michael Maltzan was commissioned to design a building devoted to Inuit art. Momentum continued to build in 2015 when the Nunavut government decided to loan its collection of art, about 7,400 pieces, to the WAG until it had built its own art and heritage centre.

Ground was broken in February 2018 for an Inuit art centre and it received its name, Qaumajuq, in October 2020.

“It actually happened. I still can hardly believe it,” Coward Wight says.

Fast-forward to 2021, and Coward Wight was among those who spent five weeks selecting, arranging and placing about 4,500 stone sculptures from both the WAG and the Nunavut government’s collection in Qaumajuq’s Visible Vault.

It’s a tangible creation of more than 60 years of foresight going back to a time when cars sported fins and Elvis sang hits.

“With our digital platform there will be four screens around the vault and people can zoom in on a shelf or on a piece and find out about it,” she says.

“Every shelf was figured out in advance and it’s all organized by community. When you visit the vault, you can walk around Baker Lake, you can walk around Pangnirtung and Cape Dorset. You can see the different stone types that are used in the different communities and the different styles and artists.”

While the WAG’s Inuit art collection and its rich history will have a place at Qaumajuq, the new gallery will also draw future generations of Inuit artists who are already challenging perceptions of what people from the North can create, says Kablusiak, an Inuvialuk artist born in Yellowknife who was part of the curation team for INUA, Qaumajuq’s first exhibition.

“You know when something sounds so good, you’re like, ‘This can’t be real, it sounds way too good.’ To see it come to life, years later, I need to give my head a shake because it’s so surreal,” Kablusiak says.

“The opportunities that are going to rise for Inuit artists in the future are going to be so exciting.”

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca Twitter:@AlanDSmall

Alan Small

Reporter

Alan Small was a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the last being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.