Massive gallery, powerful messages INUA, Qaumajuq's first exhibition, offered curators large-scale opportunities and challenges; the installations speak to the painful, dehumanizing treatment suffered by Inuit at the hands of missionaries and government officials

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 19/03/2021 (1709 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The inaugural exhibition at Qaumajuq includes a shipping container that serves as an audio-visual installation, a giant poetic textile that is about 10 metres tall and a replica of a hunting shack used by one of Canada’s greatest filmmakers.

INUA, an Inuktitut acronym short for Inuit Nunangat Ungammuaktut Atautikkut and translates to “moving forward together,” also includes a bust of an Inuit person wearing a hooded parka, the face replaced with a code: W.3-1258.

While the serpentinite sculpture’s size is small when compared with the larger works of INUA and of Qilak, Qaumajuq’s giant three-storey main gallery, W.3-1258 makes a huge statement that will be difficult for visitors to forget.

That’s because W.3-1258 is a self-portrait by Inuvialuk sculptor Bill Nasogaluak.

“This piece, W.3-1258, that’s my Eskimo identification number,” he says. “That’s who I was known as, W.3-1258, not as Bill Nasogaluak. The title is very significant to this piece. And why? It’s flat, no features. I was trying to bring across to the viewer that we were faceless. We were just a number.

“I could look up at school and beside my name it would say W.3-1258. That’s why there’s no features on it. We were faceless. It’s a portrait of myself, because that’s my number, that’s all I was ever known as.”

In Inuit tradition, elders name newborn children after parents, grandparents, other ancestors or important friends. Those single-word names are used among friends and other Inuit while others use them as their legal names. For instance, Kablusiak, Nasogaluak’s grand-niece and one of the curators of INUA, is also the name of Nasogaluak’s mother.

Missionaries and government officials had difficulty pronouncing the traditional names. In response, federal officials in 1941 gave Inuit tags to wear around their necks or on their parkas with an identification code that the government used for record-keeping.

Nasogaluak grew up in Tuktoyaktuk, N.W.T., but now lives in southern Ontario. Since he was from the western part of the Arctic, or Inuvialuit, his ID begins with the letter W.

“It was powerful. I didn’t allow myself to think about it too much because I’d cry all day and not get any work done,” Kablusiak says of W.3-1258, which was commissioned by the Winnipeg Art Gallery for INUA.

“But his work is so beautiful and powerful and I think it’s a really great opportunity to shine a spotlight on this history a lot of people don’t know about for some reason.

“I’m learning that a lot of people don’t know about the history of that, which is super-disheartening. Both my parents have numbers, aunts and uncles. It’s a really long history that ranges all across the North.”

Krista Ulujuk Zawadski, the curator of Inuit art for the Nunavut government, says she sees the “E-numbers” etched into sculptures or written on drawings or prints.

“A few years ago I was on a panel at the WAG, and we were talking about E-numbers, because it was in one of the shows, and I got a little bit emotional about it,” she says.

“Someone in the audience kind of shrugged it off and said ‘it’s just like a social insurance number,’ and I just felt really hurt that people don’t grasp this history.”

Use of the identification numbers ended in 1970 when Ottawa introduced Project Surname, in which people were allowed surnames for identification.

A person’s name is a theme in one of INUA’s bigger installations, by Inuit artist Lindsay McIntyre, who is also a professor at Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver.

The work is a portion of a home from the 1950s and ‘60s and follows the life of Kiviaq, who was McIntyre’s uncle. He was born in 1936 on a trap line near Chesterfield Inlet, Nunavut, but was given the name of David Ward by his white stepfather, who took him to Edmonton.

Ward became a top amateur boxer and tried out with the Canadian Football League’s Edmonton Eskimos in 1956. He became a city councillor in Edmonton during the 1970s and ran for mayor. When his bid fell short, he went back to school and earned a law degree, becoming Canada’s first Inuit lawyer.

He successfully fought government agencies and the Law Society of Alberta to legally change his name to Kiviaq, and the installation shows his law society certificate with Kiviaq printed on it, among other mementoes and photos he kept during his life. He died of cancer in 2016 at the age of 80.

His story is well told in the 2006 film Kiviaq Versus Canada, a documentary by Nunavut filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk, who follows Kiviaq’s story and his battle for greater rights for Inuit when dealing with the federal government.

Kunuk is from Igloolik, Nunavut, an island between the mainland and Baffin Island. He has an identification number, too, and since he grew up in the eastern Arctic, his starts with an E.

“In the olden days, the government couldn’t pronounce our names right because we inherit names of our forefathers,” he says. “When I was born, I was named after my grandmother, so my father called me Mother.”

The filmmaker is best known for directing the 2001 movie Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner, the first to be written, directed and acted entirely in Inuktitut. It earned the Camera d’Or prize at the Cannes Film Festival, and in 2015 was named the greatest Canadian film of all time by the Toronto International Film Festival.

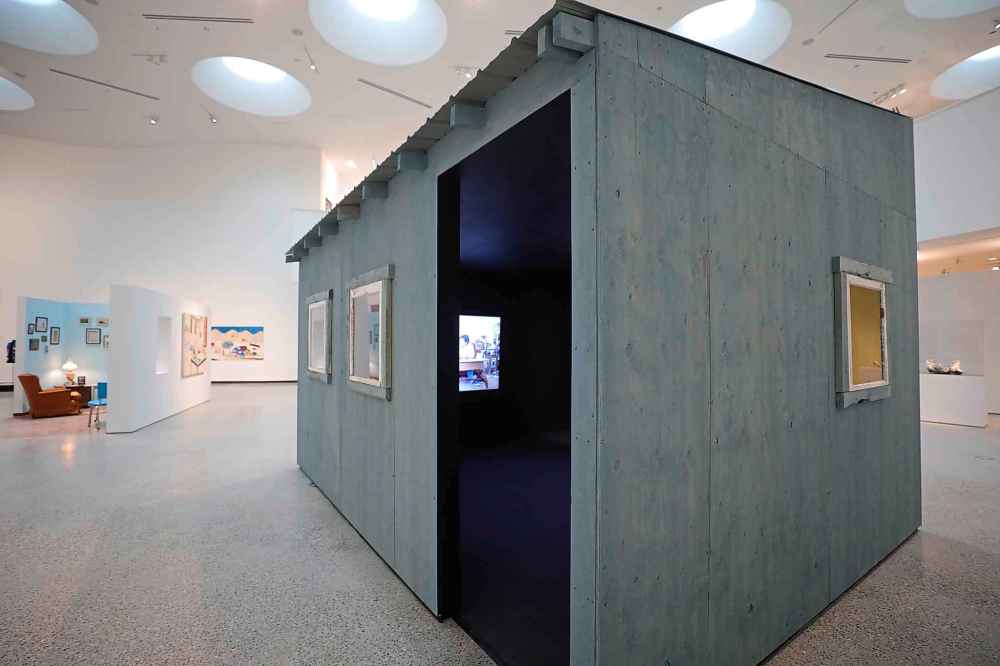

Kunuk’s hunting shack, or at least a re-creation of it, is another of INUA’s large installations. Instead of weapons there are four television screens that show modern life in Nunavut, says co-curator Heather Igloliorte. There are youngsters learning crafts, an elder skinning part of an animal and public hearings into an expansion of an iron-ore mine on Baffin Island.

“This is Inuit-owned land, right down to the core of the Earth,” Kunuk says, explaining that hunters who live off the land notice how the mine is affecting their prey.

“Right now the main concern is the iron dust is falling on the land. Animals like foxes are turning red, rabbits are turning red, ptarmigans are turning red…. The mining company is more concerned about their proposal, they want to build a railway, they want to double their (production) and the people in the area are concerned about what they eat, so it’s a big controversy going on.”

These larger installations would be difficult, if not impossible, to fit into a regular-sized art gallery. There is nothing regular about Qilak (pronounced key-lack). It is the Inuktitut word for “sky,” and its height, wide-open space and 22 skylights evoke the vastness of the Arctic and the Prairies.

Igloliorte, who is from Nunatsiavut, in Labrador, but is also a professor of art history at Concordia University in Montreal, recalls the opportunity and challenges that Qilak presents.

“Not only were we working with all that vertical space and that great big room with no straight lines, also we had to think about how the exhibition would look like from the mezzanine level, because you can look down over the exhibition,” she says. “What does this look like from a bird’s-eye view?”

A poetic tapestry by Greenlandic performance artist Jessie Kleemann drapes across almost the entire three-storey gallery, and a salon-style arrangement of Inuit wall hangings climbs up another of Qilak’s walls. Much of Qilak’s white walls remain exposed, showing the opportunity for future exhibitions to take advantage of the gallery’s height.

“I’m excited to see what other curators do in that space in the future because it’s so big. I hope that artists walk in there and they think ‘Wow I never thought about a work that’s 40 feet tall or 100 feet in diameter,’” Igloliorte says.

“We’re kind of freed up from those impositions of what galleries are supposed to look like, so maybe that will help artists think more freely about what their work will look like.”

The COVID-19 curveball forced the all-Inuit curatorial team — Igloliorte, Kablusiak, Ulujuk Zawadski and Nunavik curator Asinnajaq — to use computer programs and video-conferencing apps to work with WAG curators and designers Jocelyn Piirainen, Nicole Luke, Mark Bennett and Kayla Bruce to create INUA.

Normally curators are on site and decide where each artwork should be placed, but it wasn’t until January, during INUA’s installation, when they were all able to travel here to see the space in person.

“I couldn’t wrap my brain around it. It didn’t feel real,” Kablusiak says. “For so long we were looking at the layout in this (3D modelling) program called SketchUp, which helps to place artworks. I kind of got used to the space looking at a computer screen and all of a sudden, this is a real place that exists.

“The scale is so immense. Even the ceiling height, I found myself staring at the building for a couple of days, in awe.”

While Qilak is certainly striking, the curators believe INUA will also create moments of awe, even with smaller items, such as Inuit jewelry that has been part of the Nunavut government’s art collection, that has been rarely, if ever, viewed by the public.

“We hope we are setting an exciting new direction, not for just how the (gallery) exhibits Inuit art but how the whole world exhibits Inuit art,” Igloliorte says.

“We hope people appreciate that this is us trying to show an Inuit way of looking at Inuit art.”

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca Twitter:@AlanDSmall

Alan Small

Reporter

Alan Small was a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the last being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.