A portal into our past Le Musée de Saint-Boniface is the perfect place to ponder the changing perceptions of Manitoba’s founder, Louis Riel, and the role he played in protecting Métis and minority rights in Canadian confederation

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/02/2024 (691 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the Louis Riel permanent display at le Musée de Saint-Boniface, kept safe under glass, is an old, slightly battered cribbage board that once belonged to the man himself.

It’s an unprepossessing item, not much to look at, at first glance. But it was a source of comfort to an imprisoned Riel as he faced a date with the hangman’s noose.

Alone in his cell in the weeks after his trial, one in which he was found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death by hanging, Riel would pass the time by playing cribbage.

His guard, North West Mounted Police Cpl. Arthur Clifton Tabor, was his opponent, right until that fateful day on Nov. 16 1885, when Riel, walking toward the scaffold where he would meet his death, handed the board to Tabor.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS The cribbage board that belonged to Louis Riel, who, while imprisoned, played cribbage with one of his guards, Cpl. Arthur Clifton Tabor, to whom he gave the board prior to his execution on November 16, 1885.

The board remained in Tabor’s family for generations, before making its way to the museum via a family member.

“This larger than life figure… imagine Riel in his jail cell going ‘15-2, 15-4 the rest don’t score,’ playing this all the while knowing death was coming for him… this board, that game, this humanizes him,” says historian Philippe Mailhot, who retired in 2014 after a 25-year tenure as the museum’s director.

It is items like this that give visitors to the Saint Boniface Museum a glimpse into the life of a man whose fight to defend the rights and identity of the Métis people is now etched in the annals of Manitoba history.

Free Museum entry on Louis Riel Day

Entry to Le Musée de Saint Boniface Museum is free on Louis Riel Day, Feb. 19. The museum is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. There will be entertainment on the day including fiddle players. Visitors are encouraged to explore the Riel exhibit.

Entry to Le Musée de Saint Boniface Museum is free on Louis Riel Day, Feb. 19. The museum is open from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. There will be entertainment on the day including fiddle players. Visitors are encouraged to explore the Riel exhibit.

The museum also offers guided tours, however they have to be booked ahead of time.

Housed in the original Grey Nuns’ Convent, built between 1846-51, the museum sits in a neighbourhood central to the francophone and Métis identity.

The building itself at 494 Tache Ave. is the oldest building in Winnipeg and is the largest traditional oak-log structure still standing in North America. The still visible rough-hewn walls showcase Red River framing, a locally popular construction technique of squared logs mortised and set into upright logs.

The permanent Riel exhibition, thoughtfully curated to highlight objects that plot a tight narrative of his life and achievements, sits in the left wing of the museum.

A large number of displayed items came from the Queen’s Own Rifles as “trophies of war” collected following the Battle of Batoche, while others were donated by both members of the public and descendants of the Riel family.

“When you create an exhibit, there is a story and a theme that goes around it,” says Cindy Desrochers, the current museum director. “The narrative here was focused on trying to tell the story of Riel, the battles, and what led to his death. It is very condensed. It’s a story that we can explain to people, to provide them a bit of history, which then allows them to understand the struggles the people of the Red River had.

“Winnipeg was struggling at the time with the different tensions between both sides of the river, of cultures, of languages. It’s the story of Riel wanting to protect all those people and trying set up a government that was representative of them and the challenges he faced against the federal government afterwards.”

Some display cabinets contain innocuous objects — his blue woolen tuque, slightly moth-eaten but still in a relatively good state — while others represent more fraught times, such as an example of a surveyor’s chain from that era. It was the government of Canada’s decision to try to re-survey existing Métis farms for prospective settlers and Riel’s defiance — by literally stepping on the chain — that marked the beginning of the Red River Resistance.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS The surveyor’s chain played a big role in

igniting the Red River Resistance.

Other items reflect the lasting legacy of the man. A reprint of the Riel-drafted Métis Bill of Rights, which contained protections of the rights of the French-speaking predominantly Catholic Métis people, hangs on a wall.

“The Louis Riel collection has always been an integral part of the museum. It deals with Indigenous and Métis people from their perspective, not as an impediment to the British Commonwealth. Saint Boniface Museum had already interpreted Riel as a good guy right from the outset. This was a fellow who did what he did for the sake of the future of Western Canada and his people,” Mailhot says.

The eldest son of a St. Boniface Métis family, Riel’s fate wasn’t always set for the noose.

Louis Riel timeline

Oct. 22, 1844: Louis Riel is born in the Red River Settlement.

1858: Archbishop Taché sends Riel to Lower Canada to be educated for the priesthood. Riel is 14 years old.

1864-66: Upon death of his father in 1864, Riel withdraws from college to work and support his family. He finds work in Montreal as a law clerk.

1866-68: Riel works in Chicago and St. Paul, Minn.

1868: Riel returns to the Red River Settlement.

Oct. 22, 1844: Louis Riel is born in the Red River Settlement.

1858: Archbishop Taché sends Riel to Lower Canada to be educated for the priesthood. Riel is 14 years old.

1864-66: Upon death of his father in 1864, Riel withdraws from college to work and support his family. He finds work in Montreal as a law clerk.

1866-68: Riel works in Chicago and St. Paul, Minn.

1868: Riel returns to the Red River Settlement.

July 1869: William McDougall, Canada’s minister of public works, orders a survey of the Red River Settlement.

July 19, 1869: Riel speaks at a meeting of Métis residents about rights in the event of annexation of Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) lands by Canada.

August 1869: Riel speaks on the steps of St. Boniface Cathedral; declares Dominion Government plans to conduct a land survey a menace.

Oct. 11, 1869: Métis horsemen led by Riel stop the Dominion Government land survey.

October 1869: Led by John Bruce, Métis National Committee is formed.

Oct. 25, 1869: Riel appears before the Council of Assiniboia and declares the National Committee will block entry of any governor unless union with Canada is based on negotiation with the Métis and the population in general.

Nov. 2, 1869: Lieutenant-governor is met at HBC Pembina post by Métis patrol and ordered to return to the United States. Upper Fort Garry is taken over by the Métis.

Nov. 6, 1869: Riel asks English speaking residents to elect 12 representatives from their parishes to attend a convention with Métis representatives.

Nov. 16:1869: HBC Governor Mactavish orders Métis to lay down their arms.

Nov. 23, 1869: Provisional government is proposed by Riel.

Dec. 1, 1869: Transfer of British North America lands of HBC to Canada takes place. Riel presents his List of Rights to the convention.

Dec. 7, 1869: John Christian Schultz and followers of Canadian Party temporarily imprisoned.

Dec.8, 1869: Provisional Government formed. John Bruce named president.

Dec. 27, 1869: Riel replaces John Bruce as president.

Feb. 10, 1870: List of Rights approved to negotiate provincial status with federal government.

Feb. 17, 1870: Riel’s provisional guardsmen arrest 48 armed men, so-called Canadians, at Upper Fort Garry. Their leader, Dr. John Schultz escapes capture and leaves for Ontario.

Mid-February, 1870: Charles Boulton, commander of the 46th militia regiment and survey crew member, is condemned to death to set an example to Canadians who had twice attempted to overthrow Riel. Riel later pardons him in exchange for a promise the English parishes will elect representatives.

March 4, 1870: Thomas Scott is executed. Arrested Feb. 17 as one of the 48 Canadians, history describes him as a foul-mouthed, ignorant bigot who had previously escaped imprisonment, had attempted to incite civil war and continued to show contempt for guards. He was charged with insubordination, and tried and sentenced to death by a jury. Riel, apparently believing it was time to demonstrate his provisional government should be taken seriously, refused to intervene, rejecting all appeals.

May 12, 1870: Manitoba Act is passed (name favoured by Riel) and receives Royal assent.

June 24, 1870: Provisional government accepts terms of Manitoba Act.

July 15, 1870: Manitoba Act takes effect. Riel is just 25 years of age.

Aug 24, 1870: Wolseley expedition arrives; Riel vacates Upper Fort Garry. Fearing he will be lynched, he moves to the U.S.

February 1871: Riel falls ill, perhaps enduring a nervous breakdown, worrying about his personal safety and his inability to support his family.

May 1871: Riel returns home to St. Vital.

March 2, 1872: Riel goes into voluntary exile in St. Paul, Minn., at the request of prime minister John A. Macdonald, who supposedly wanted to reduce tensions and help avoid conflict between Quebec and Ontario.

Sept. 14, 1872: Georges-Etienne Cartier wins Manitoba seat in federal election when Riel withdraws candidacy as a favour to Macdonald.

1873: Cartier passes away.

October 1872: Riel elected to Parliament, but never enters to take his seat, fearing he would be arrested for murder.

February 1874: After Macdonald’s government resigns, Riel is re-elected in February 1874, but is expelled from Parliament before taking his seat.

September 1874: Re-elected a third time in a Provencher constituency by-election, Riel delays taking his seat and is once again expelled.

October 1874: Riel is convicted along with Ambroise Lépine for murder of Thomas Scott.

January 1875: Death penalty is commuted by Governor General to two years of imprisonment.

February 1875: Alexander Mackenzie’s Liberal government grants amnesty for Riel and Lépine, on the condition both remain in exile for five years.

1875-1884: Riel lives in New York; marries Marguerite Monet, 1881 (three children); takes U.S. citizenship in 1883; teaches in Montana in 1884.

July 1884: Called by Métis residents to Batoche, North West Territories (now Saskatchewan).

May 9-12, 1885: The Battle of Batoche is a decisive defeat for Métis forces against the much larger and better-armed Canadian militia commanded by Maj.-Gen. Middleton. The Northwest Rebellion is over. Riel turns himself in to Middleton and is taken to Regina.

Nov. 16, 1885: Riel, at 41 years of age, is found guilty of high treason and hanged in Regina.

— source: Province of Manitoba

One of 11 children, the young Riel was destined for a life of religion and was sent to Montreal at 14 to train for priesthood. However, he was never ordained. He needed to go to work, first in Montreal, then Chicago and St. Paul, Minn., after his father died.

In 1868, news of growing unrest in the Métis settlement reached him while in St. Paul. When he saw for himself the state of matters upon his return, Riel began to champion the cause of the Métis, seizing control of Upper Fort Garry before forming a provisional government — the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia — with himself as the leader.

He drafted the List of Rights, which he presented to the Canadian government in early 1870. This bill went on to become the Manitoba Act, establishing the province as Canada’s fifth.

However, it was a decision during this time that ultimately determined Riel’s fate. Allowing the March 1870 execution of Thomas Scott, an Ontario Protestant who was part of an uprising that wanted to overthrow the provisional government, resulted in the Canadian government sending troops to Manitoba and forced Riel into exile.

Riel returned years later to help the Métis in what is now present-day Saskatchewan in their struggles with the Canadian government. The 1885 Northwest Rebellion culminated in the Battle of Batoche and Riel’s eventual surrender to the government.

Marked a traitor, he was charged with high treason and sentenced to death by hanging.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS

“It’s a story that we can explain to people, to provide them a bit of history, which then allows them to understand the struggles the people of the Red River had.” says Cindy Desrochers.

Considered both a hero and a villain, public perception of the “rebel” started to shift through the 20th century. In 1992, he was declared the founder of Manitoba and in 2008 the third Monday in February was proclaimed as Louis Riel Day.

Riel’s rehabilitation, from traitor to resistance leader, was cemented late last year when the honorary title of Manitoba’s first premier was bestowed upon him.

“Education has played a great role in changing the perception of Riel. Louis Riel was seen as a traitor, a murderer of Thomas Scott. The history and facts have not changed; what has changed is the interpretation and teaching of them,” Mailhot says.

“What I find really interesting about Louis Riel is that if someone today were to find something belonging to him, it would make national news. It is a big deal. It shows where Louis Riel sits in the mythology of Canadian history.”

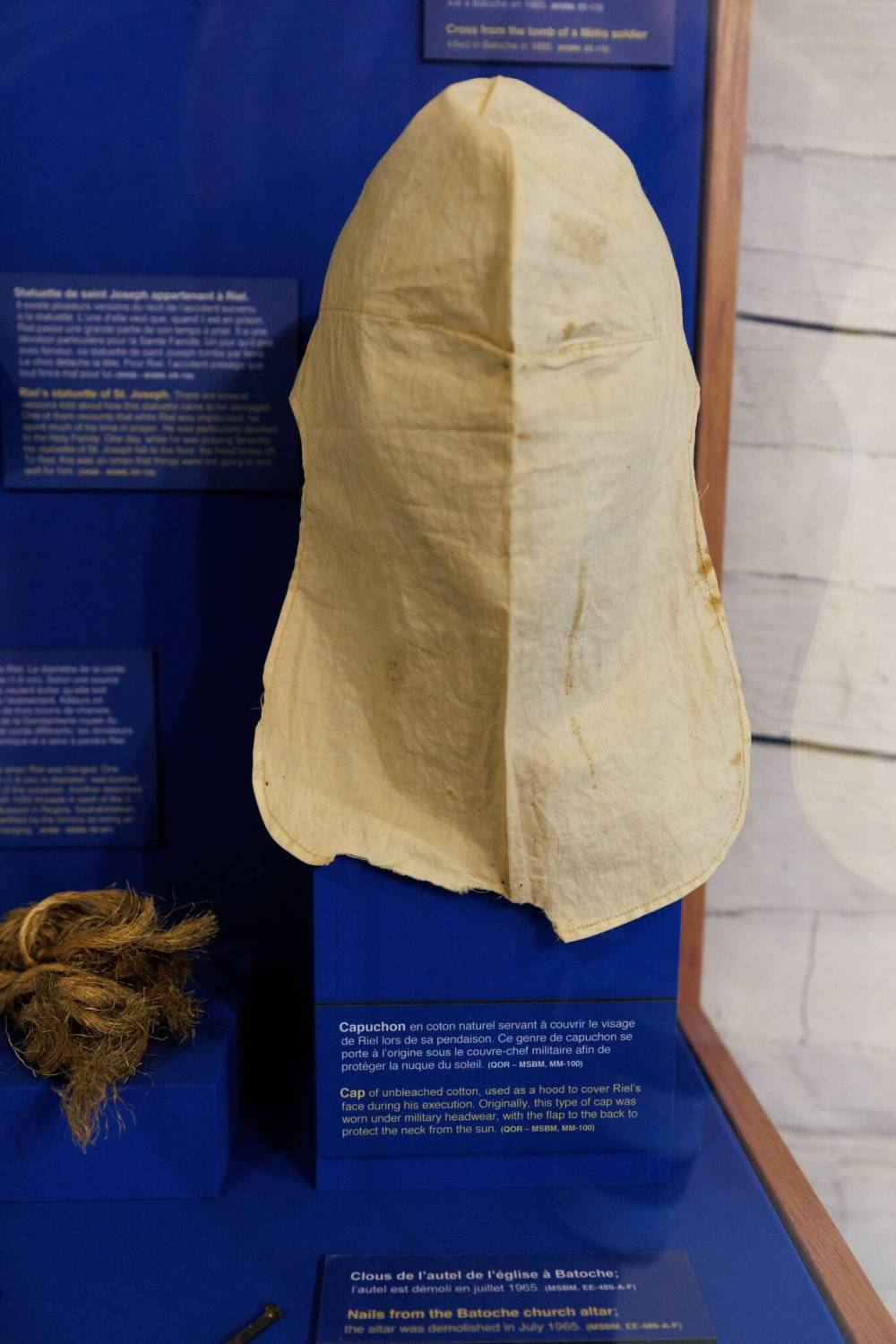

Items directly related to Riel’s execution are also on display at the museum.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS The vamp of Riel’s moccasins is decorated with multi-coloured silk thread embroidery, edged by plaited red-and-white porcupine quills, as well as two rows of fine horsehair cord.

In a glass display case is a headless statue of St. Joseph, whom Riel considered the patron saint of the Métis people.

There are multiple stories of how the statue came to lose its head. In one, it fell off a shelf and broke while Riel was praying in his Regina cell. He took this to be a portent of ill omen.

Another version states the statue was actually at his mother’s house at the time of his imprisonment, and a strong gust of wind had knocked it off a table, its head breaking the exact moment Riel was executed.

“There are a whole bunch of stories. In a version in a book there are two statues, which both lost their heads at the same time,” Mailhot says. “One artifact can generate multiple stories.”

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS The collection includes a fragment of a suspender, taken as a memento from Riel's body.

Just a few inches away from the statue is an envelope containing strands of the rope said to have been used in his hanging. These came to the museum by way of Jennifer Roblin, daughter of former Manitoba premier Duff Roblin.

According to Mailhot, she said it had been sent by the military officer who was at the execution to an anti-Riel minister in Winnipeg.

“Somehow it had ended up in the hands of the premier of Manitoba, despite the fact that newspaper articles of the day said the rope was burned. My guess is a number of people took pieces of rope from the noose,” Mailhot says.

”I am prepared to defend our pieces as being authentic.”

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS A soldier’s cap was used as a hood to cover Riel’s face during his execution.

In the same display case sits a piece of unbleached white cotton, a soldier’s cap, the back flap turned into a hood. It was placed over Riel‘s face before the noose tightened, his neck snapped and he choked to death. The cap came to the museum by way of the Queen’s Own Rifles’ collection, one of a number of artifacts, which also included hair clipped from his lifeless body.

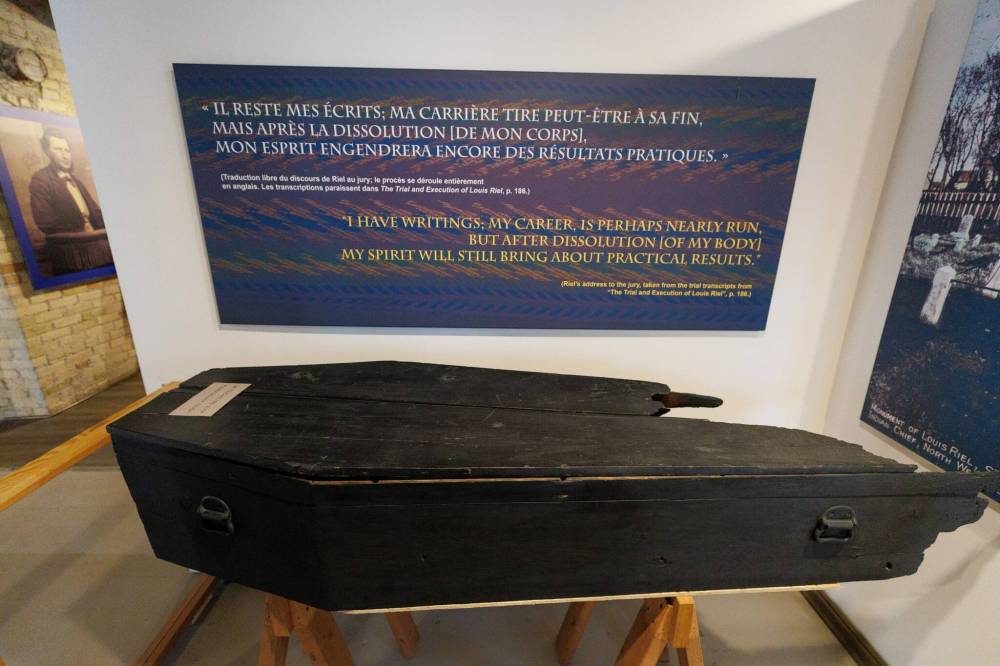

In a corner of the room, tucked to one side, is the coffin that held his body as it travelled back from Regina to Winnipeg. Damaged in the 1968 St. Boniface Cathedral fire, it had been kept by the Riel family for many years, before they eventually donated it to the museum, which was at that time in the cathedral basement.

But not everything in the display is so macabre. In the case where the cribbage board is displayed there is also a pair of soft moccasins, one slightly more faded than the other, which Riel wore while in prison. It is believed they were removed from his body by Rev. C. McWilliams, acting chaplain for Riel at the execution. Beside them sits some more hair, this time lovingly clipped and tied in a ribbon; a mother’s keepsake of her beloved eldest child.

It’s a precious collection, a snapshot of a man who wore many cloaks — traitor, martyr, saviour. A man who is now considered the founder of Manitoba and its first premier.

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS The coffin to transport Riel’s body from Regina to Winnipeg was later damaged by fire.

“This is the important part of a physical artifact: that you can look at it and you can say this person was a living, breathing human being, he had friends, he had family, he is a real person,” Mailhot says.

“What this museum does, what the Riel items do, is provide an invitation to draw people to the institution where they will learn more about the Métis people, more about the fur trade, more about the francophone community in Manitoba. It is the door through which other things can open up.”

av.kitching@freepress.mb.ca

AV Kitching is an arts and life writer at the Free Press. She has been a journalist for more than two decades and has worked across three continents writing about people, travel, food, and fashion. Read more about AV.

Every piece of reporting AV produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.