Diving into history

Mammoth Lake Agassiz finally gets its due in book by Free Press journalist

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/11/2017 (2940 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

An excerpt from Lake Agassiz: The Rise and Demise of the World’s Greatest Lake (publisher: Heartland Associates Inc.). Free Press writer Bill Redekop will be launching his new book on Nov. 8 at 7 p.m. at McNally Robinson Booksellers.

Going to the lake?

We say that a lot in Manitoba. “Are you going to the lake?”; “I’m going to the lake.” Or, “We’re headed to the lake this weekend.” That kind of talk pings around office walls and work yards on Friday afternoons.

“The lake” is local vernacular for any lake one happens to visit regularly and Manitoba has thousands of them. In fact, we have more lakes, and we go to more lakes, than anyone else in North America. Ours may be a prairie province, but we have a lake culture.

Geologists or those who study geology for any length of time might react differently to that question. “Going to the lake? I don’t have to go to the lake,” they might say. “I’m already in it.”

Manitobans live inside the footprint of Lake Agassiz. For thousands of years, Lake Agassiz was the lake of all lakes, a behemoth in strength and influence, and the largest lake in the world for at least 1,000 years. And yet, it’s the lake most of us know least.

Today, Manitoba has 100,000 lakes. Lake Agassiz, though its size fluctuated dramatically through history, was typically twice the size of all Manitoba’s 100,000 lakes combined. It was even larger than all the Great Lakes combined.

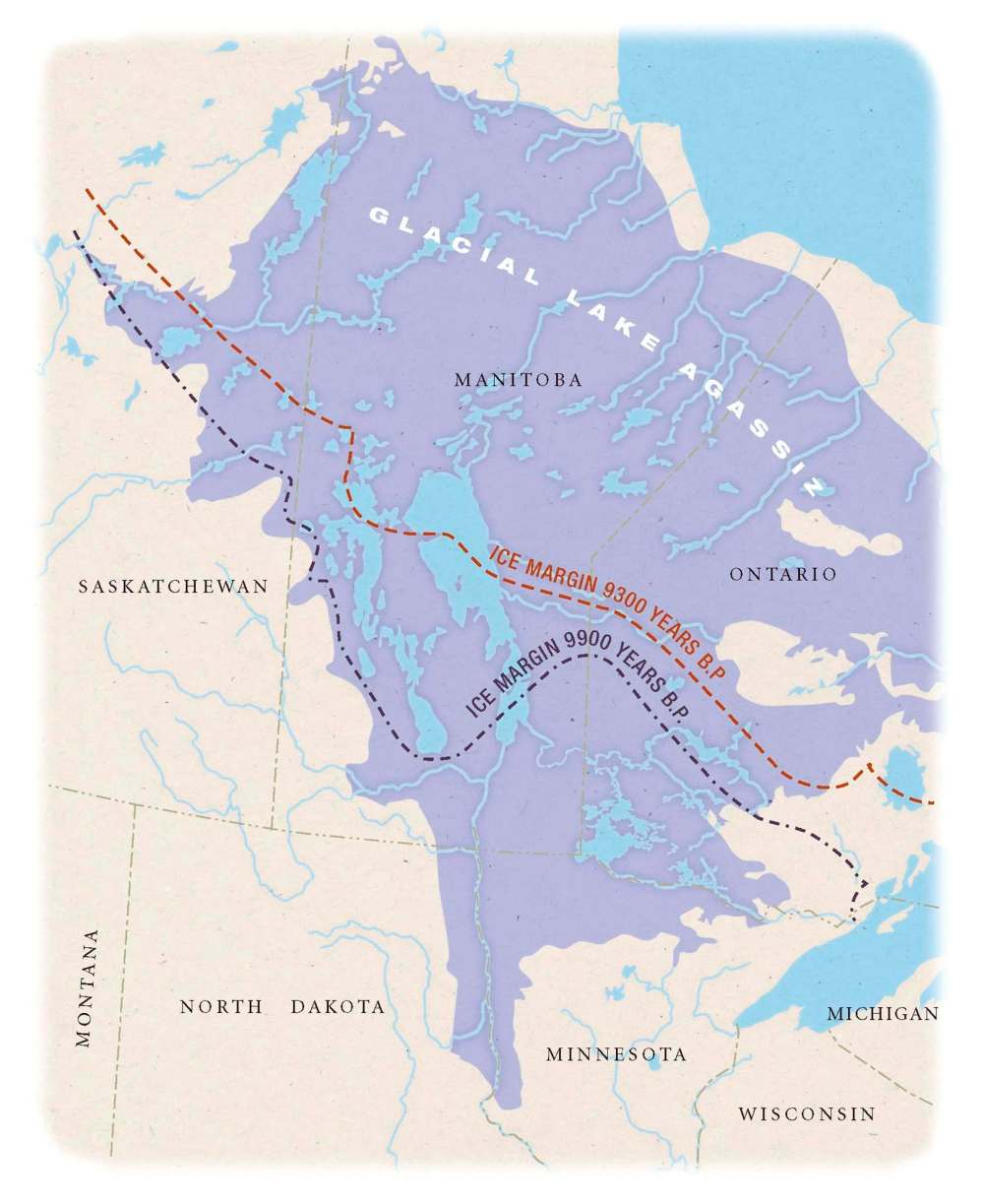

There’s often confusion for novice readers about Lake Agassiz’s size because its boundaries kept changing. For starters, Lake Agassiz was always migrating north, as its northern glacial boundary melted and it pulled up stakes to the south. Minnesota and North Dakota, for example, were vacated earliest in its history.

Many documents list Lake Agassiz’s size as the area it covered in its entire 6,000-year history. In total, Lake Agassiz submerged an area of 1.5 million square kilometres, though not all at one time. Even if one excludes the last few hundred years when Lake Agassiz and Ontario’s glacial Lake Ojibway merged, Lake Agassiz still covered 950,000 square kilometres.

Its total area stretched as far as Brandon in the southwest, about 13,000 years ago. A giant bay cut into the east side of Brandon; the west side would have been beachfront property.

To the east, Lake Agassiz covered Lake of the Woods for 3,000 years. It extended as far as Rainy Lake and Sioux Lookout in Ontario, and lolled like a giant tongue south into North Dakota and Minnesota. The trough of the Red River now runs like a seam down the middle of that former glacial lake tongue.

It covered the town of Swan River in northwestern Manitoba, though just barely. It extended all the way north to within 200 kilometres of Hudson Bay before the great Laurentide Ice Sheet, which formed Lake Agassiz’s northern shore, finally collapsed.

In fact, Lake Agassiz, which originated about 14,000 years ago, covered nearly the entire province at one time or another, except for the southwest. It didn’t spread into the southwest because of the Manitoba Escarpment, or Pembina Escarpment as it’s called in North Dakota. The escarpment was high enough to contain Lake Agassiz, but its waters spread like a Red River flood everywhere else.

As a result, most Manitobans do live “in the lake.” Winnipeg, Portage la Prairie, Steinbach, Morden, Winkler, Dauphin, Flin Flon, Thompson and part of Brandon were all submerged by Lake Agassiz at one time or another; Fargo-Moorhead and Grand Forks-East Grand Forks were deluged to the south. So, we don’t have to go anywhere to get “to the lake.” About 95 per cent of us are already in it.

We are like SpongeBobs living on a dry lake bed. Lake Agassiz formed our present-day geography. It’s the reason for our flat landscape; for our rich agriculture; for the sandy beaches where we swim and for the sand ridges running north and south, called paleoshorelines, that for millennia we’ve used for foot paths, ox cart trails, railroads, highways, cemeteries and town sites. This book will point to many paleoshorelines running through Manitoba that you routinely drive over, likely without knowing it.

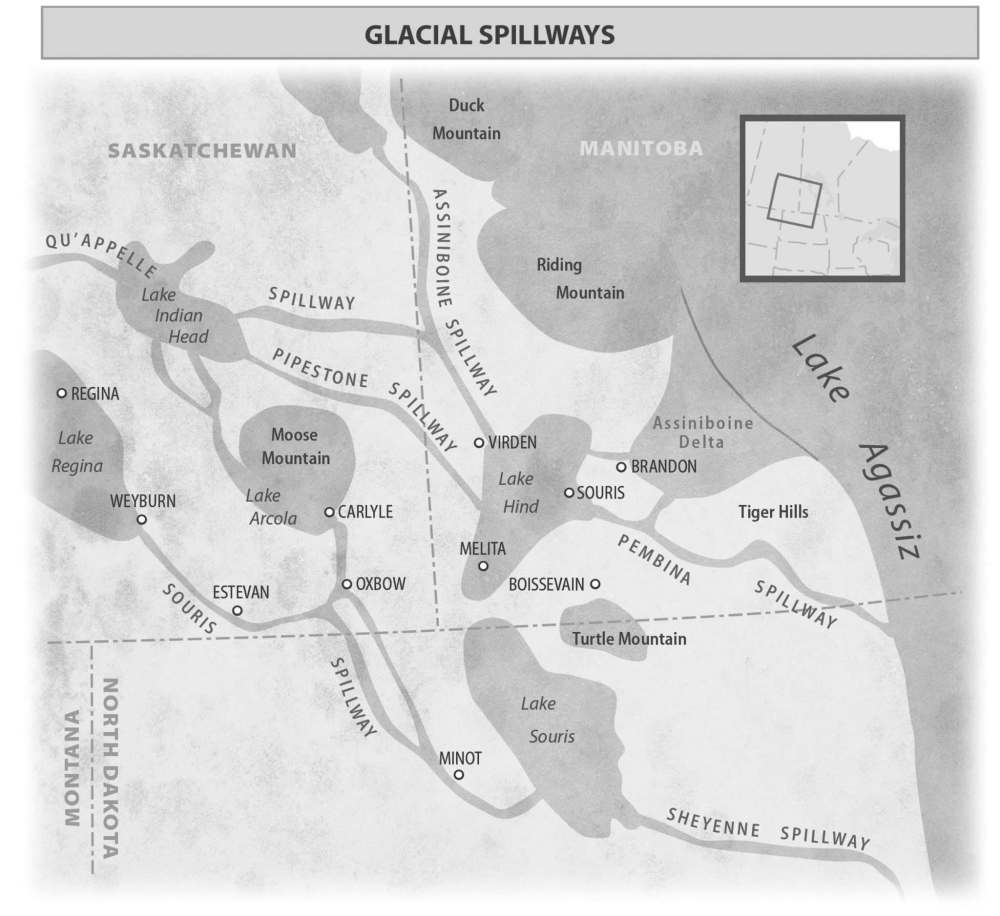

And Lake Agassiz helped build our valleys. Many smaller glacial lakes burst their ice dams, sending tsunamis of water rushing into Lake Agassiz. These torrents of meltwater carved our giant valleys, called spillways. The glacial Assiniboine River dug one such spillway, the majestic valley west of Brandon. Then it created a delta starting at Brandon, where it emptied into Lake Agassiz. That sand and gravel delta stretches east from Brandon to Portage la Prairie, a distance of 130 kilometres. This delta also encompasses Neepawa and Gladstone to the north, and runs as far south as Highway 2, almost to Carman. Imagine a river flowing into a lake and creating a delta that size. There was nothing puny about Lake Agassiz. It was immense.

At the end of the great lake’s life, a horseshoe-shaped ice dam about 200 kilometres wide curved around the bottom of Hudson Bay. This was all that held Lake Agassiz back. When that ice wall gave way, Lake Agassiz released a volume of glacial fresh water so great that it not only raised sea levels, but dropped global temperatures by interrupting ocean currents. That’s how powerful it was.

The definition of a glacial lake is a body of water hemmed in by continental ice on at least one side. Glacial Lake Agassiz was created by a giant glacial wall that blocked Manitoba’s natural drainage to the north. How high was this glacial wall? Think of this. The ice sheet that covered Manitoba from the last glaciation was more than three kilometres thick at its glacial hub just west of Hudson Bay. At Winnipeg, it was between one and two kilometres thick, for the ice sheet thinned as it travelled in all directions from its hub. But imagine standing on a raft at the edge of the ice sheet at today’s corner of Portage and Main; you’d fall over trying to look at the top, for the ice cliff was at least 10 times higher than the Richardson Building. Or, put another way, if the height of the glacier at Winnipeg was laid horizontally, like a sidewalk, it would take about 20 minutes to cross it at a good clip.

● ● ●

When temperatures began to warm about 20,000 years ago, the ice sheets stopped advancing and the blanket of ice that had buried much of North America began to melt. The ice sheets started giving back the water they had pilfered for thousands of years. That was how Lake Agassiz formed in the low centre of North America.

It took time for land to be exposed in Manitoba.

Fifteen thousand years ago, much of Alberta was ice-free, whereas ice hadn’t even started to retreat from Manitoba until 14,000 years ago. That melting of continental ice in Manitoba, and indeed in the Rocky Mountains, coincided with Lake Agassiz’s lifespan 14,300 to 8,200 years ago.

The Laurentide Ice Sheet also served to block the glacial water’s natural flow north. The ancestral Red River ponded against the ice sheet’s walls, as did the tributaries that flow today into the Red. In essence, all the waterways that directly and indirectly drain into Hudson Bay today were held back by the ice sheet and formed Lake Agassiz. That’s a lot of water. But many other glacial lakes were draining into Lake Agassiz, as well. Water from as far away as the Rocky Mountains, and nearly as far east as Thunder Bay, drained into Lake Agassiz, as did water from North Dakota and Minnesota. It all ponded at the base of the soaring wall of ice.

Of course, the ice cliff on Lake Agassiz’s northern border also contributed vast stores of water. So while water was flowing off lands from the south, east, and west into Lake Agassiz, it was also pouring off the ice sheet to the north. Meltwater cascaded off the ice cliff in surface channels. Chunks of glacial ice collapsed into the lake, and calved off as floating icebergs. Meltwater runoff tunnelled into the glacier, forming rivers tens of kilometres long. Some of the deepest ponding was at Winnipeg as it is near the bottom of a bowl-shaped landscape between east and west. Lake Agassiz was up to 210 metres deep over Winnipeg, which explains why we still flood today. Winnipeg isn’t just a meeting place of early cultures at the confluence of the Assiniboine and Red rivers, but also a place where waters met, ponding and flooding before heading off to Hudson Bay.

Lake Agassiz wasn’t Canada’s only glacial lake. It wasn’t even the only glacial lake in Manitoba. There were also glacial lakes Hind to the southwest and Proven up on the escarpment. Saskatchewan had glacial lakes Regina and Assiniboine, while Glacial Lake Souris lay on North Dakota’s boundary with Manitoba. But none of these came close to matching Lake Agassiz in size or duration. In fact, they all emptied into Lake Agassiz. No place in North America was more saturated than Manitoba.

Glacial lakes were forming in Europe and Asia, too, thanks to continental glaciers. The ice sheet in Europe ranged as far south as Germany and Poland. But no other ice sheet in the world came close to the size of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which covered Canada and the northern United States west to the foothills of the Rocky Mountains.

The Laurentide Ice Sheet didn’t just block drainage, and then add to flooding by melting. It also weighed down the landscape, causing Earth’s crust to sink by up to a kilometre in northern Manitoba. This meant that the land sloped even more steeply northward than it does today. That sloping pinned Lake Agassiz’s waters against the receding glacial boundary. Those waters, in turn, with their stored heat, contributed to the warming and melting of the glacier wall. As the ice melted, land freed of its great weight bounced back. At first, it bounced back vigorously, relatively speaking. It has since slowed but even today, it’s still rising. It will keep rising for another 10,000 years, with most of that recovery in the north, where it was depressed to a greater degree.

As indicated earlier, geologists now believe the glacial lake existed from about 14,300 to 8,200 years ago. That’s a bit more than previous estimates of the lifespan of Lake Agassiz, which ranged between 4,000 and 5,000 years. Improved technology is responsible for these updates.

Lake Agassiz was like a Rorschach test in its various reconfigurations. The lake kept shape-shifting as glacial lobes advanced or as new drainage outlets were opened or blocked. It often took on a serpentine shape, with its neck and spine snaking along the curved margin of the melting ice sheet. Lake Agassiz’s total area spanned a distance of more than 3,000 kilometres from east to west, and 1,500 kilometres north to south. It extended 350 kilometres (or nearly 220 miles) south into the United States. It covered virtually all of Manitoba, as well as parts of Ontario, Saskatchewan, North Dakota, South Dakota and Minnesota.

When it’s said that Lake Agassiz submerged a total area of 1.5 million square kilometres during its lifespan, that figure includes its merger in the last 500 years of its existence with glacial Lake Ojibway, a large but short-lived glacial lake in northern Ontario and Quebec. When they merged, Lake Agassiz grew to 841,000 square kilometres. Its northern shore stretched from Quebec to Saskatchewan. At that size, it became the undisputed largest lake in the world. No other lake came close. When it broke through the Laurentide Ice Sheet into Hudson Bay, it unleashed a quantity of fresh water so massive that it not only raised sea levels but interrupted ocean currents, causing a drop in global temperatures.

However, not all researchers recognize that last phase as Lake Agassiz but rather as a new, merged lake, Lake Agassiz-Ojibway. Excluding that late phase, Lake Agassiz inundated a total area of 950,000 square kilometres. During that stage, it was, at its largest, 263,000 square kilometres and it was then that it formed Manitoba’s famous Campbell Beach ridge, one of the most prominent paleoshorelines in the world. The witty “Agassiz Beach” sign put up by locals on the Yellowhead Highway at the turnoff to the village of Arden, is on the Campbell Beach. The lake was 50 metres deep over much of its range during the Campbell Beach phase, but reached depths of more than 200 metres along the eastern boundary where the two-billion-year-old Canadian Shield and much younger Phanerozoic limestone meet.

Was Lake Agassiz still the largest lake in the world at that level? The challengers for “the largest lake” title were the Caspian Sea, the Black Sea and Chad Lake bordering the Sahara Desert in Africa, according to Jim Teller, professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba’s Department of Geological Sciences, and regarded as one of the world’s leading experts on glacial lakes.

What about glacial lakes in Siberia? While there were glacial lakes in Siberia, none matched the size of Lake Agassiz, in part because a much smaller ice sheet covered Siberia, compared to the Laurentide Ice Sheet in North America, resulting in much less meltwater.

Among its challengers, probably the greatest is the world’s largest lake today, the Caspian Sea, said Teller, which now covers an area 394,299 square kilometres. But the Caspian was much smaller during Lake Agassiz’s existence. Archaeologists have found remnants of early human settlements inside the lake’s current shorelines, indicating that they were much closer together than they are today. The same can be said of the Black Sea. It, too, was considerably smaller then. Like Lake Agassiz, these prehistoric lakes kept changing in size as the last glacial period ended. During these changes, Lake Agassiz would have been larger than any lake on the planet.

“Lake Agassiz was the largest lake in the world for thousands of years,” said Teller. “I can stand behind that claim for some of its history, even before the merger with the Ojibway.”

So why not brag? If Lake Agassiz was the largest lake in the world, even for a nanosecond, Manitoba should start printing the “Home of the World’s Largest Glacial Lake” brochures. Yet there’s little acknowledgement that this was once not only the centre of the ice age, but also the centre of the world’s largest lake. There is virtually no tourist literature, road signage or information boards telling locals or tourists about Lake Agassiz. Yet, why shouldn’t this information be part of our basic knowledge? Or even the basis of our tourism strategies?

● ● ●

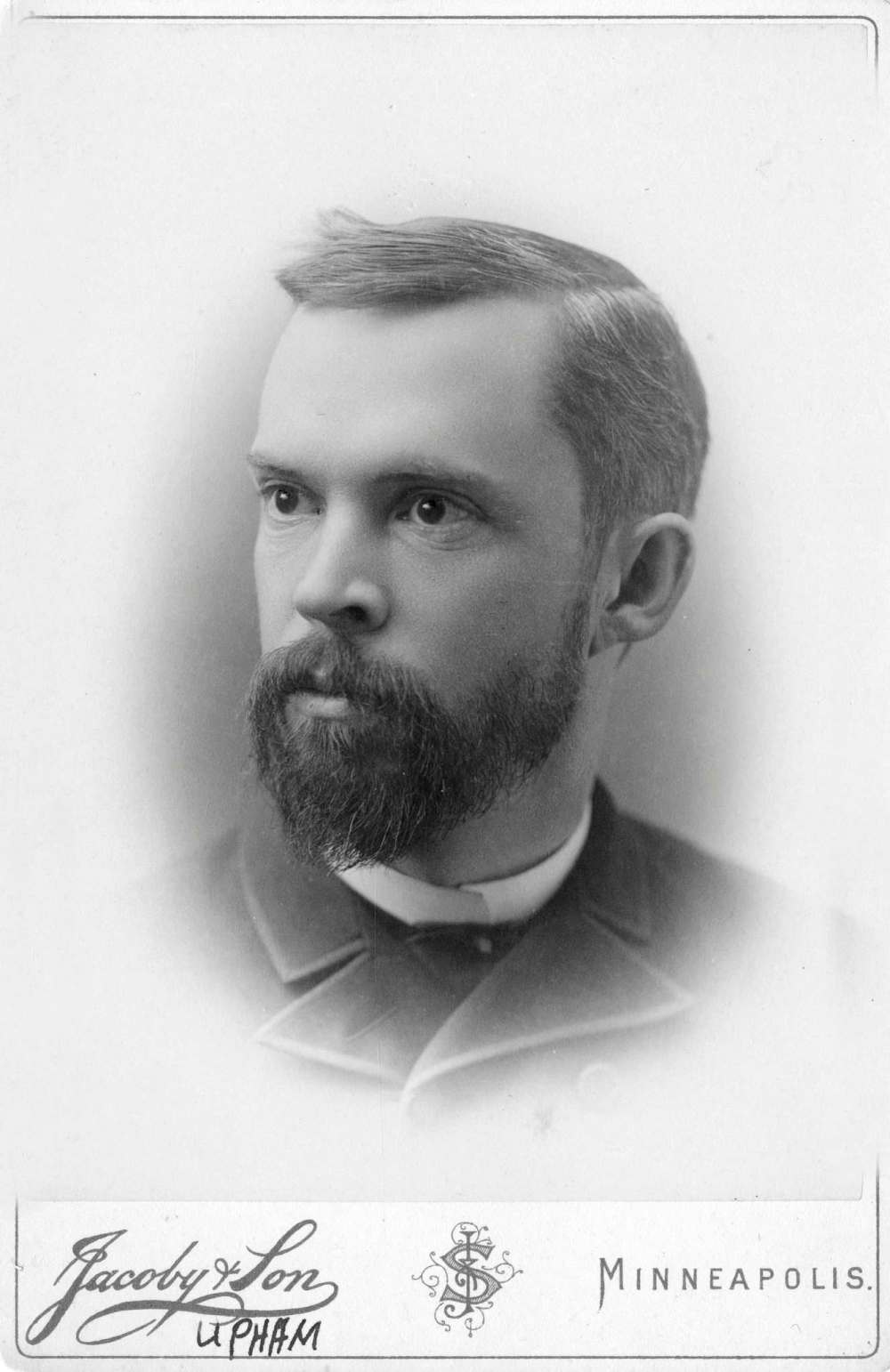

IN THE LATE 1880s, Manitobans could have been excused for such ignorance. No one knew anything about Lake Agassiz when Warren Upham, a studious, well-mannered geologist from Minnesota, trekked across Manitoba on horseback. He frequently dismounted to measure and take sediment samples of what he believed were the former shorelines of a gigantic lake. Many people got a good laugh out of that. The public was still trying to digest a new theory from Europe that there had once been an Ice Age, a lengthy frigid period that attired much of the globe in ice. Now they were hit with the idea of a gigantic phantom lake. Here was this shy, withdrawn American out mapping the landscape, knocking on farm doors and asking for information about people’s soils and their farm wells, and taking copious notes. People undoubtedly smiled and winked at each other.

But farmers are respectful people. There would have been a few jokes made in local shops, and locals would have regarded Upham as a curiosity, but as he roamed the countryside, trying to learn the secrets of the land, he would have also found a warm reception. People in the country are always willing to discuss the mysteries of the earth from which they derive their livelihoods. By the end of the conversation, he would have been received like a member of a secret brotherhood.

One of those, whose name appears in the back notes of Upham’s papers, was John A. Davidson, the founder of Neepawa. Upham went around asking people about soil records from the drilling of their wells. What soils and sediments had the drill core penetrated to give clues to the land’s history? Davidson obliged. Upham’s notes from him read: “well, 60 feet, the deepest in the town; soil, 2 feet; gravel and sand of the Assiniboine delta, 12 feet; and (glacial) till, dark bluish, with the usual proportion of gravel and boulders, 46 feet; water good.”

You can see the history there: soil, recent history; sand, Lake Agassiz history; till and boulders, glacial history.

Davidson would go on to be a member of the Legislative Assembly in Manitoba in Hugh John Macdonald’s Conservative government, and served briefly as finance minister. But he’s best known for his grave marker in Neepawa’s Riverside Cemetery, the sculpted seraph made famous in Margaret Laurence’s novel, The Stone Angel.

Upham was just 29 when he started his explorations. It took him 15 years, wandering the lonely countryside of Manitoba, Minnesota and North Dakota for extensive periods, to complete his work. In one three-year span, he travelled nearly 18,000 kilometres by horseback, and by horse and wagon. His monograph, a book-length essay, is still hailed as a masterpiece today. The Glacial Lake Agassiz, by Warren Upham, was published in 1895. Yet, outside geological circles, we barely know him — or the body of water he named Lake Agassiz.