History of lost lake makes a big splash

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/12/2017 (2843 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

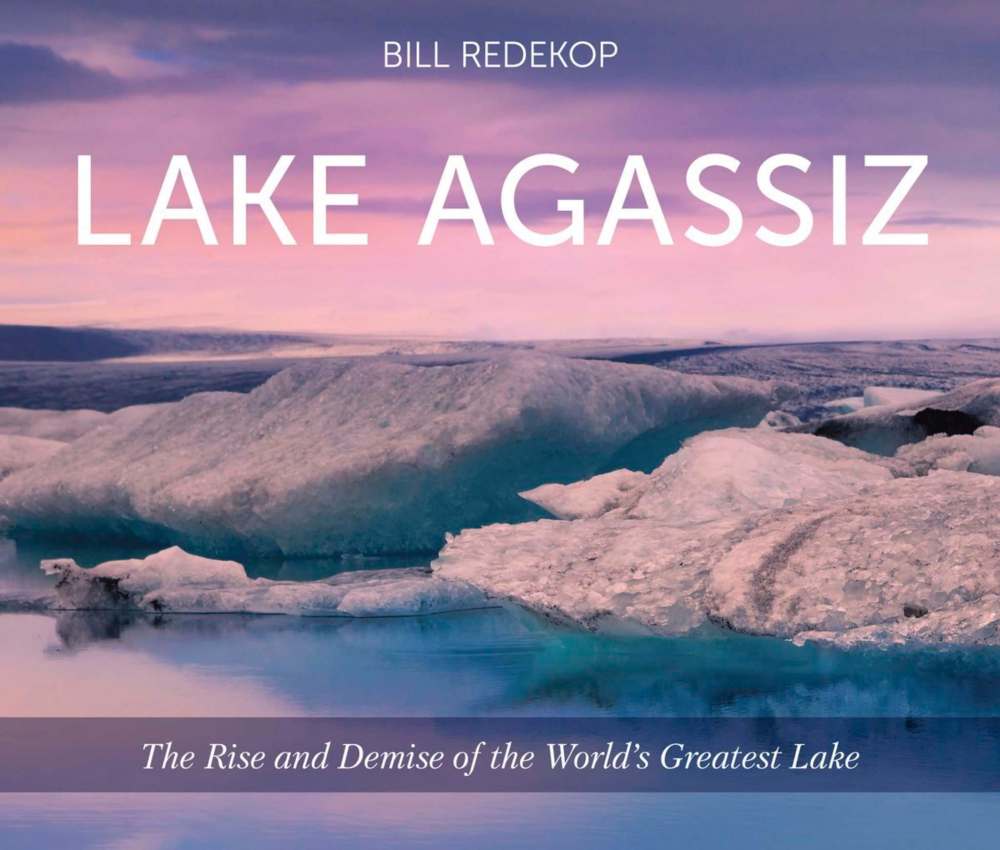

Through his reporting for the Free Press, Bill Redekop has been introducing Manitobans to their own province for years through his upbeat profiles of interesting people and places.

He approaches the much more complicated task of telling us about Lake Agassiz in the same non-technical language so we can all understand, calling on a crowd of experts to help tell the story of the lake and generously acknowledging his debt to them.

Although the great lake was the largest in the world in its day, covering much of what is now Manitoba, as well as northwestern Ontario and portions of Minnesota and North Dakota, it disappeared around 8,000 years ago. So how can we know anything about it?

Redekop answers this question from many different angles, starting with the “discoverers” of the lake. In 1837, Louis Agassiz, a Swiss scientist and professor, lectured on the idea that Europe must have been covered with thick ice sheets in the past. He was one of several who developed similar theories about ice ages, but he was a showman, and so got more of the credit.

Agassiz continued to lecture, and taught at Harvard when he immigrated to the U.S., becoming something of a scientific celebrity. He never spoke about the lake that bears his name, however, and the closest he got to Manitoba was Thunder Bay during an 1848 scientific trip.

The lake was named after Agassiz by a much more self-effacing scientist and admirer of Agassiz named Warren Upham. Upham travelled around North Dakota and Manitoba for several summers in the 1880s, searching for evidence that a vast lake had once covered the area. He was not the first to suspect the existence of a lake, as is so often the case in science, but Upham might be said to have proven the lake’s existence. Mapping many kilometres of the gravel beaches that once bordered Lake Agassiz and recording a great deal of other evidence, Upham began to make the lake visible to modern eyes. He worked for the U.S. Geological Survey; it was that body which published his work The Glacial Lake Agassiz, which presented his conclusions about the lake.

Agassiz and Upham are only two of the large number of scientists Redekop profiles in the story of the lake. Discussing the many different issues surrounding its history, he introduces the scientists who developed our knowledge about them.

There are also chapters on mammoths and other large mammals that lived in the area while the lake existed.

Redekop details the evidence that people also lived and hunted along the lake’s shores, discussing the arrow and spear points dating from the time that have been found. He gives us chapters on geological features such as the Manitoba Escarpment and the delta of the ancestor of our present Assiniboine River, and examines the origin of Bird’s Hill.

The book is fascinating reading. It’s easy to foresee an increase in traffic on certain country roads as people follow the book’s directions to places where one can still see the remains of the lake’s gravel beaches or scale the ancient Manitoba Escarpment.

The book is also beautifully designed, with numerous excellent maps and photos credited to Dawn Huck and Peter St. John, the designer and photographer, respectively (among other duties), at Heartland Associates. One small complaint: like many of Heartland’s books, Lake Agassiz is printed in landscape format. This makes it awkward, for this reader anyway, to hang on to while reading.

But this is a fine book that skilfully gathers a great wealth of information about our ancient past in one place and presents it in an entertaining and interesting way.

Jim Blanchard is a retired librarian and local historian.