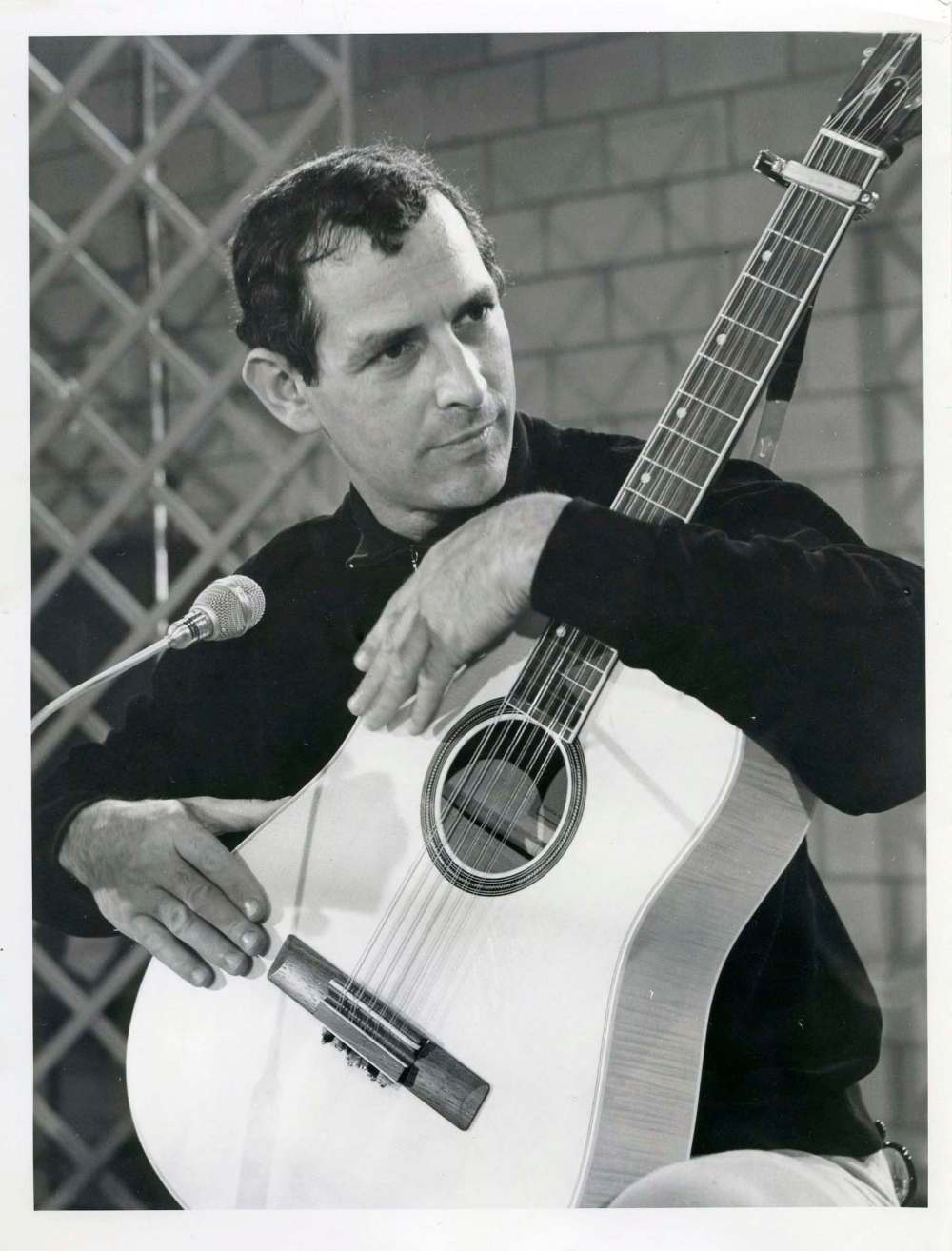

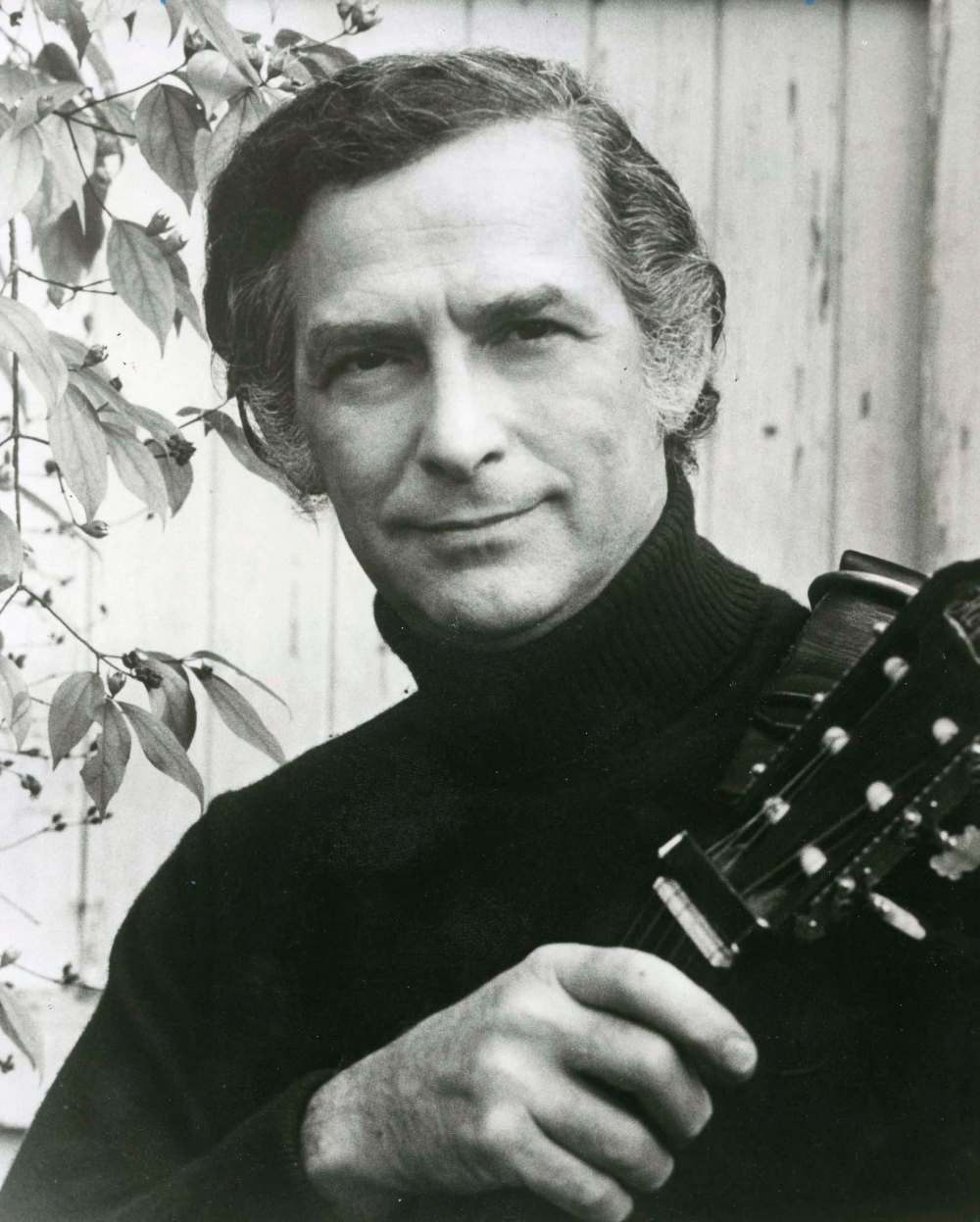

Folk hero

Brand, raised in Point Douglas, became music pioneer

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/10/2016 (3367 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Here’s a trivia question: the Sesame Street character Oscar the Grouch is named for what Winnipegger? The answer: folk music legend, singer-songwriter and broadcaster Oscar Brand.

“I was on the original board of the Children’s Television Workshop,” he told me a few years ago from his home in Great Neck, N.Y. “And I was so fastidious about everything that I gave people a hard time. So they named the grumpy character after me.”

‘Oscar Brand was a modern-day troubadour, and like Pete Seeger, he brought peopletogether to raise their voices in song’– record producer and musician Dan Donahue

Brand died of pneumonia Sept. 30 at the age of 96. He taped what became the last of his Folksong Festival radio shows on New York’s WNYC the week before. His weekly show ran for a record 71 years, the longest-running show with a single host, Guinness World Records says.

In a recent article on Brand, the New York Times wrote, “Every week for more than 70 years, with the easy, familiar voice of a friend, Mr. Brand invited listeners of the New York public radio station WNYC to his quirky, informal combination of American music symposium, barn dance, cracker-barrel conversation, songwriting session and verbal horseplay. Everyone who was anyone in folk music dropped by. Woody Guthrie — Woodrow Wilson Guthrie, as Mr. Brand called his rambling friend — was known to burst in unexpectedly to try out a new song. Bob Dylan told a riveting tale about his boyhood in a carnival, not a word of it true.”

Dylan made his radio singing debut on Brand’s show shortly after arriving in New York from Minnesota in 1961.

Brand was a true renaissance man and one of the most celebrated artists in the world. He wrote for Broadway and film, recorded more than 90 albums, hosted television shows in both Canada and the United States, penned books and was outspoken on critical social issues. He also composed one of Canada’s greatest folk music songs, Something to Sing About (This Land of Ours), a hit for Canadian folk group the Travellers.

“I was in a unique position,” he recalled, “because I had one foot in Canada and one foot in the States. I would do well in both, but it was the doing well in Canada that I liked the best.”

“Being a musician wasn’t enough for him,” says longtime manager and close friend Douglas Yeager from his office in New York.

“He had to be busier. He wrote books, produced and narrated over 300 documentaries, wrote several plays for Broadway. His interests were broad and not confined exclusively to music. He interviewed the likes of Eleanor Roosevelt — who became a friend and even babysat his children — Buckminster Fuller, Supreme Court justices. The opportunities were endless, and he always pursued them. He had a zest for life and a keen curiosity.”

Born Feb. 7, 1920 to a Jewish family in Point Douglas, Brand recalled, “I grew up on Lusted Avenue with a big open field at the end of it back then. It was an exciting time. I can remember horses on the street and my brother tickling their hooves and trying to ride them as they galloped away. Lusted, to me, was a perfect picture of Canada.”

His father, an early settler in the Portage la Prairie area, was a linguist employed by Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd. to greet newly arrived immigrants.

“He knew all the languages. At age 14, he started as a translator for the (indigenous people). He’d learn their languages. The Hudson’s Bay Co. hired him. He led an interesting life.”

Brand’s extended family was equally colourful. “One of my relatives was an ice carrier, another was a smuggler,” he told me. Brand was introduced to music via a player piano.

As a youngster, Brand witnessed discrimination first-hand with the way First Nations people were mistreated. That had a profound influence on him at an early age and shaped his attitude and actions for the remainder of his life.

Born with one leg two inches shorter than the other and only half a calf muscle (he wore specially made shoes throughout his life), Brand’s parents moved the family to Minneapolis before briefly staying in Chicago and ultimately ending up in New York when he was 11 years old, seeking medical care for Brand’s disability.

“We never wanted to leave,” he said. “We loved Winnipeg and Manitoba.”

Despite becoming a naturalized American, Brand continued to call Winnipeg home.

“It was always Winnipeg for me,” he said. “I always came back, even when people were fleeing Winnipeg. I bounced back and forth between Canada and the States, but I always thought of Winnipeg as my home.”

Brand graduated from Brooklyn University in 1942 with a degree in psychology (“I couldn’t get into a college in Canada,” he said) and served as a psychologist in the U.S. army during the Second World War, assessing the suitability of young men for combat duty. Despite his handicap, Brand was proud of the fact he completed boot camp alongside other recruits.

Following the war, he joined WNYC radio after offering his services for a Christmas show, presenting songs most people had never heard — including one about Santa’s body odour. He was invited to return the following week, and this informal arrangement evolved into Oscar Brand’s Folksong Festival, a winner of two Peabody Awards. He also began writing, both music and books, as well as recording. One of his songs, A Guy Is a Guy, became a hit for Doris Day in 1952.

“The original iteration of that song, I think I learned in Montreal,” he told me. “It was really about the British soldiers and dated back to the 1700s as I Went to the Alehouse (A Knave Is a Knave). It became No. 1 around the world for Doris Day.”

Brand’s songs have been recorded by Ella Fitzgerald, Harry Belafonte and the Smothers Brothers. In addition, he wrote commercials for Maxwell House coffee, Log Cabin Syrup, Cheerios and Oldsmobile, among others. He even published a music book titled How to Play the Guitar Better Than Me.

Brand composed the music for two Broadway musicals, A Joyful Noise starring John Raitt (father of Bonnie Raitt) and The Education of Hyman Kaplan featuring Hal Linden and Tom Bosley. He scored ballets for Agnes de Mille, wrote music for documentary films, hosted the children’s television shows The First Look and Spirit of ’76 and composed the music for the 1968 off-Broadway production How to Steal an Election.

Folksong Festival became a folk music institution.

“Every folk singer who came to New York wanted to be on Oscar’s program,” folksinger Jean Ritchie told Newsday in 2005. “He also lent money to the poor ones.”

Ritchie recalled Brand putting her on his show soon after she arrived from the Kentucky mountains. The two remained lifelong friends. Other guests included the Weavers with Pete Seeger, Judy Collins, Harry Belafonte, Joan Baez, Phil Ochs, Harry Chapin, Emmylou Harris, B.B. King, Odetta, Theodore Bikel, Dave Van Ronk, Tom Paxton, Suzanne Vega, John Denver and Woody Guthrie’s son Arlo, who as a teenager gave one of the earliest performances of his song Alice’s Restaurant on Folksong Festival. In 1995, Brand won a Peabody Award for “more than 50 years in service to the music and messages of folk performers and fans around the world.” Folksong Festival also featured African folk music, including a rare performance by a Nigerian student vocal chorus in 1956 while that country was still under British colonial rule.

“Oscar was an early champion of many African-American artists including Leadbelly (one-time prisoner Huddie William Ledbetter) and Josh White, both of whom he met in 1940,” notes Yeager.

Brand met Woody Guthrie, Burl Ives and Pete Seeger around that same time.

“When these people all arrived in New York along with Oscar, the folk music community was created,” Yeager says. “That was the first folk music revival. There was no folk music industry in the early 1940s. No record labels were recording it. Oscar was the last surviving member of that group of pioneering folk musicians.”

In a feature article on Brand’s passing headlined Rest in peace Oscar Brand, the man who built the foundation for modern folk music, the Observer noted, “Oscar Brand may not have been the face of folk music, as, say, Seeger or Dylan were, but he was the rock upon which the church was built. Through his radio shows, his songs, his concerts, his TV shows and his documentaries, he did more to build the framework for modern folk music than any man on our continent.”

“Oscar had an encyclopedic knowledge of music of all kinds, not just folk music,” says Yeager. “There was no one in the 20th century who knew more about North American music. He could tell you the history of a folk song that might date back to the 14th century in Ireland. He was often consulted in court cases as a specialist on the authenticity or history of a song in cases where there was a dispute over plagiarism.”

Besides his appreciation for the music of Leadbelly, White and other African-American performers, including Len Chandler, Brand’s ace was the fact he had a car and would drive these artists to their out-of-town gigs. “They let him be their opening act,” says Yeager, “and that way he could drive them and get them food along the way because they couldn’t go into restaurants nor buy gas because they weren’t white. He always believed that they deserved the same opportunities that white people had.”

As Brand told the Boston Herald, “You couldn’t have whites and blacks in the same audience in those days.” Brand also participated in civil rights events, including joining marchers in Selma, Ala., in 1965.

During the anti-communist witch hunts of the early 1950s, he was blacklisted from television and concert performances after the pamphlet Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television — which listed artists who were suspected of communist leanings, including Brand — was widely circulated. Unlike several of his colleagues however, Brand was never asked to testify before the House un-American activities committee. Brand had been a regular performer on Kate Smith’s radio show beginning in the late 1940s until pressure on the network forced them to remove him from the show.

Despite the blacklisting, Brand continued hosting his radio show. When the mayor of New York complained, it was pointed out Brand did the shows for free. The mayor backed off. In fact, for its entire 71-year run, Brand never took a penny for his shows. He even booked other blacklisted performers such as Pete Seeger on Folksong Festival.

In 1963, he returned to Canada to host CTV’s Let’s Sing Out, which featured many of this country’s finest folk performers as well as newcomers such as a young Joni Anderson (later Joni Mitchell) and filmed at the University of Manitoba in early 1964. Over the years he appeared alongside the likes of Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Simon & Garfunkel, Woody Guthrie, the Kingston Trio and Pete Seeger. Switching to CBC, the show ran until 1968.

“Oscar Brand’s Let’s Sing Out was a weekly staple on the family black-and-white TV,” recalls local record producer and musician Dan Donahue, who began his career as a folk performer.

“My older brother Jim, along with his St. Paul’s College musical cohorts, were into the music of the time with the likes of Pete Seeger, the Weavers and later Bob Dylan leading the way. The show was based on the hootenanny concept, where Oscar would lead an evening of song and the studio audience, usually university students seated on the floor, would join in. I was probably learning my first few guitar chords at the time, and having spent many hours listening to brother Jim sing and strum away in his bedroom, Oscar’s show seemed like a natural extension of the musical world I was being introduced to.”

Toronto-born folksinger Bonnie Dobson, best known for her song Morning Dew, appeared with Brand several times in the 1960s. “I did a number of festivals with him including the Mariposa Festival,” she says from her home in London, England. “Oscar was a part of one’s growing up in folk music. I had his album he had made with Jean Ritchie when I was starting out. I also appeared on his television show twice. He was really knowledgeable and so very kind.”

She laughs recalling a particular performance together. “In 1967, I was performing with Oscar in the Canadian Pavilion at Expo 67. We shared the bill together. I remember coming offstage with my guitar after my first show and Oscar quietly taking me aside and saying, ‘You know, Bonnie, it doesn’t have to be loud.’”

“I always found Oscar Brand to be a passionate promoter of folk music, folk artists and singer/songwriters,” says Sylvia Tyson of folk music duo Ian & Sylvia, who knew Brand from the first Mariposa Festival. “His radio show was a very early forerunner of the now well-established Americana format in the U.S., so we have to thank him for keeping the faith. I was very pleased that we were able to honour him at the Canadian Songwriter’s Hall of Fame.”

“I did a lot of Canadian television and radio,” Brand said. “I loved the popular music of Canada. I was brought up on it. Unfortunately, many of my songs were blacklisted in the States for being too political. Canadians were a little more tolerant. But the reality was that you had to go to the States, where the business was happening. However, I always made sure there were Canadians on my programs.”

Along with Johnny Mercer, Frank Sinatra and Sammy Kahn, Brand co-founded the American Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1969 and served as its curator from the beginning.

As a founding member of the Children’s Television Workshop, Brand was instrumental in creating Sesame Street. In a 1998 interview with the Chicago Tribune, he said he wanted the show to also appeal to underprivileged inner-city children by insisting Sesame Street not present a “sanitized” view of urban areas these children would not recognize nor identify with.

“I fought for sloppy city streets, fought for garbage cans on the front steps, and winos,” he said. Much of his vision was met with deaf ears, although the committee rewarded his protests by creating a grumbling, garbage can-dwelling character after Brand.

In 1987, Brand was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Winnipeg and returned once again to his hometown in 2010 to appear at the 37th annual Winnipeg Folk Festival, where he received the Order of the Buffalo Hunt from the province. Brand had performed at the inaugural Winnipeg Folk Festival in 1974. In 2011, the festival honoured him with its Artistic Achievement Award. “I’m at an age now where they bestow honours and awards on me,” he joked. Brand holds honorary degrees from several American universities.

“Oscar Brand was a modern-day troubadour, and like Pete Seeger, he brought people together to raise their voices in song,” says Donahue. “It seems so relatively innocent by today’s standards, but out of that period emerged some of the greatest Canadian songwriters in modern history, and I’m convinced Oscar had a hand in it all.”

“He was an amazing raconteur, storyteller and the nicest gentleman you could ever meet,” says Yeager. “He had a brilliant mind, a keen intelligence and a curiosity.”

Adds Dobson, “We won’t see the likes of Oscar Brand again. Like Pete Seeger, he was seminal.”

John Einarson writes about Manitoba’s music history. Tune in to My Generation from 8 p.m. to 10 p.m. Tuesdays on UMFM 101.5 or stream it live from umfm.com.

Born and raised in Winnipeg, music historian John Einarson is an acclaimed musicologist, broadcaster, educator, and author of 14 music biographies published worldwide.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.