Discuss racism of today, not yesterday

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/01/2013 (4723 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

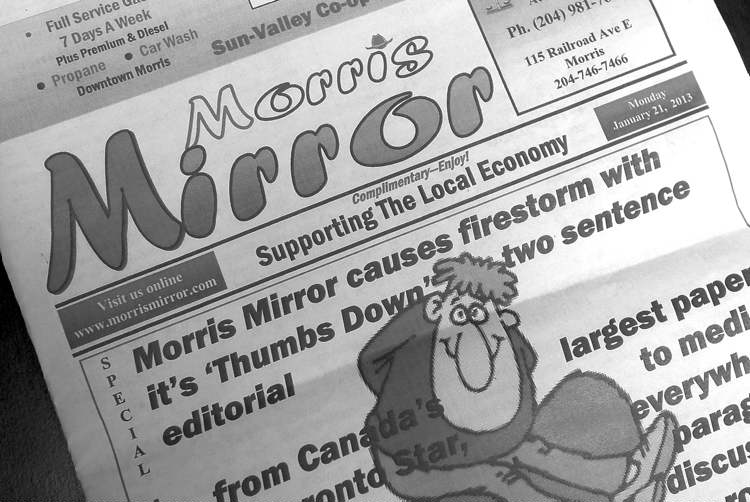

The Free Press on Saturday featured a column by Lindor Reynolds entitled Poison in a small town. In it, Reynolds discussed the publication of racist comments in the Morris Mirror by editor Reed Turcotte.

Reynolds states that Morris “was a small town like any other, before hatred oozed out.” She continued, “Turcotte dragged Morris into the 1950s American South where uppity negroes were put in their place, and that place wasn’t where decent, God-fearing white folks lived. That attitude wasn’t right then and there, and it’s not right here and now. Unless Morris wants to join Selma, Ala., in the annals of shame, it’s time to stand up and be counted.”

If there was even a remote possibility that readers still had not caught onto the analogy, she finished her piece with the words: “Montgomery, Ala. Little Rock, Ark. Memphis, Tenn. Unless Morris, Man., wants to join the roll call of shame, the majority of decent people here must stand up and agree name-calling is no substitute for reasoned debate.”

It is very common to associate racism and oppression with the 1950s and 1960s but the problem with associating racism with a single time period is that it has the effect of closing rather than opening a discussion about a much longer and influential history of racial oppression that impacts us in a very real way today.

Morris was not “dragged into the 1950s” as Reynolds suggests. Rather, Turcotte responded in a very contemporary way to a contemporary expression of indigenous resistance using language that is very commonplace in Canada: “Indians/natives” / “who in some cases are acting like terrorists” / “want it all but corruption and laziness prevent some of them from working for it.” Turcotte’s statements are not out of time with present-day, every-day racism faced by indigenous people in the media, shops, restaurants, workplaces, schools and other places.

Just as we like to claim that racism resides in our past, we also like to claim that it resides elsewhere “in places like the U.S. South.” Turcotte’s racism is not something which was somehow parachuted in from elsewhere; in its characterizations and its subject matter, it is not out of place with southern Manitoba white settler communities.

It is not enough to point to the existence of histories of racism elsewhere; the Idle No More Movement encourages us to get to know our local history of racism.

For example, representing indigenous people as backwards, inferior and incapable of governing ourselves and our lands is very much linked to efforts on the part of colonial governments to fully access, exploit and take ownership of indigenous land and resources.

Over time, successive assaults and denigrations led many to believe that the dissolution of indigenous communities and the enfranchisement of indigenous people into the Canadian state were the only way forward.

It has been conveniently forgotten that this approach sidesteps our original nation to nation relationship and that there were and are other possibilities.

Reynold’s references drawn from civil-rights-era confrontations over the extension of equality to African Americans in the end distracts from the important ways in which the theft of land and labour are linked by histories of colonialism experienced by indigenous and other racialized people throughout Canada and the U.S.

The objectives of Idle No More are not simply the inclusion of indigenous people into an otherwise healthy nation state. Rather the movement calls into question colonialism itself and calls on us to take part in building a different kind of place for our future.

A vital part of this process is to openly discuss and acknowledge the rights of indigenous people and to learn about the long history of racism in the place where we live here and now.

Mary Jane Logan McCallum is an assistant professor of history at the University of Winnipeg and a member of the Munsee Delaware Nation.