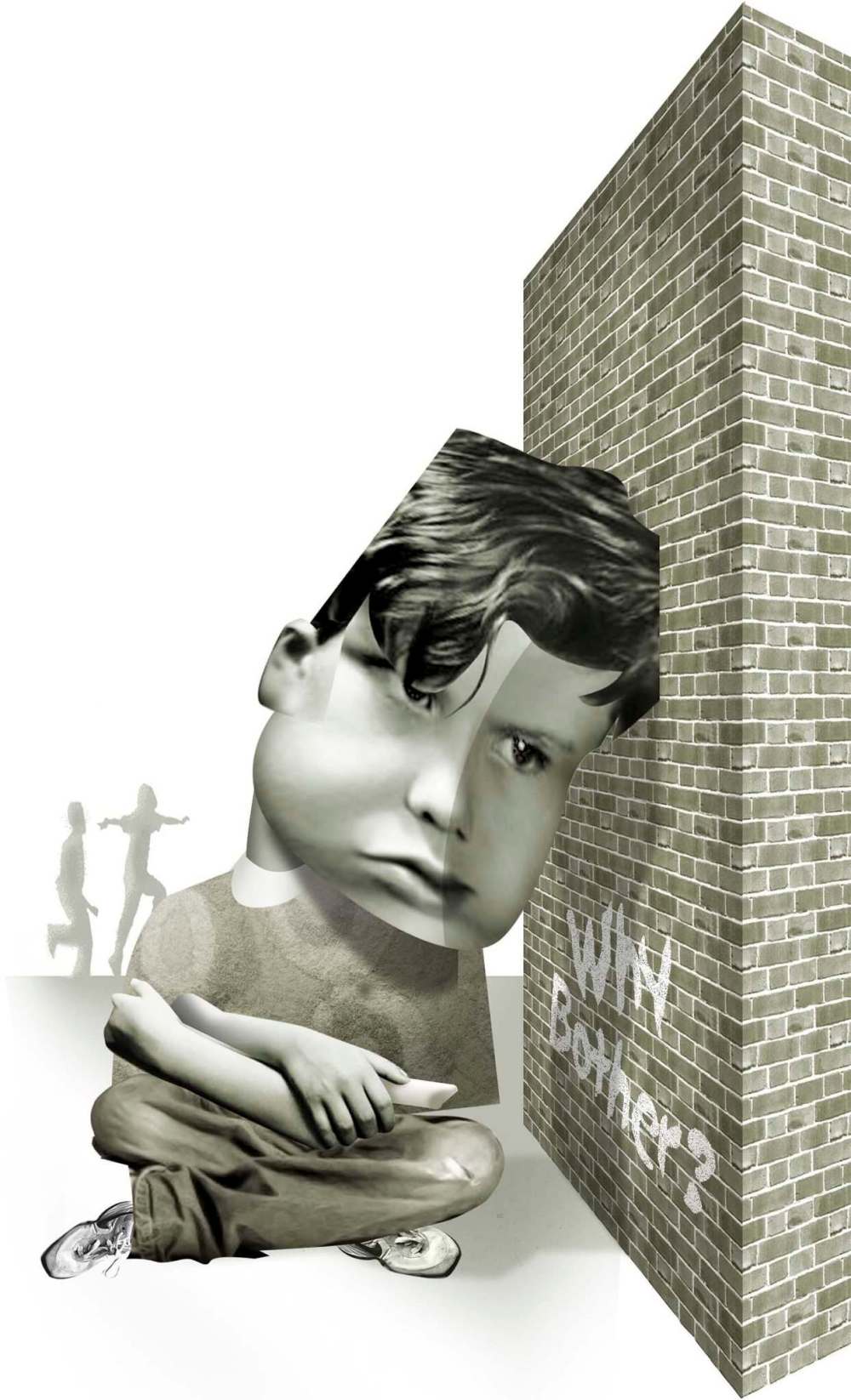

Healthy dose of education

A primer for politicians on how to fix the system

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/04/2016 (3567 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Any provincial election candidates out there got a notion how to turn around an aircraft carrier in a bathtub?

Because that’s what it might take to see significant improvements in Manitoba’s health-care and public education systems.

The jargon, just so we don’t lose the bureaucrats and professionals by the third paragraph, is “improving outcomes,” and there are for sure people out there with ideas for doing just that, but some of those ideas are just so totally far outside the comfortable middle-class norms that rule politics.

Start by preventing people from getting sick.

Well, duh.

But it’s more politically complicated than urging people to eat vegetables and not to smoke.

It can involve — brace yourself — improving social housing and putting it in more affluent neighbourhoods, providing both unemployed and low-income employed people with a guaranteed annual income and giving tax dollars to pregnant young women so they can eat better and give birth to healthier babies.

Let’s start with some advice from the exceptionally learned Dr. Brian Postl, dean of the faculty of health sciences at the University of Manitoba, from the latest edition of The Social Determinants of Health in Manitoba, published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

“We have long struggled with how to improve health performance and to bend the cost curve, but we also need a two-pronged approach, which also prevents people from getting sick in the first place. The social determinants of health are more important in determining health status than the actual health services being provided,” said Postl. “The more unequal the income gap, the more health status suffers.”

Alas, “There’s no silver bullet,” acknowledged Lynne Fernandez, the CCPA’s Errol Black chair in labour policy.

“If you want to bring down the cost of health care, the first thing you do is prevent people from being sick. There’s way more poor people who are sick — it’s working and living conditions,” Fernandez said in an interview. Inadequate housing can be cold, have mould, tenants can be under constant pressure to move. “They can’t afford to eat properly.

“You can imagine shifting your focus from a biomedical one. It’s fundamentally a political issue. Doctors will say, ‘What can we do about poverty?’” Fernandez said. “A pharmacare program would really bring down our costs.”

The U of M’s Manitoba Centre for Health Policy has seen the province achieve remarkable results by providing about 29 per cent of the province’s expectant mothers with the princely sum of $81.41 a month.

That’s the healthy baby prenatal income benefit, explained senior research scientist Marni Brownell, which pays for healthy food or makes the difference in a decent place to live, which in turn lowers the rate of premature birth and of lower birth weight. “That has been one of our exciting findings,” Brownell said. “It pays off a lot in the long run.”

The MCHP has found benefits to kids when their social housing is built in a more affluent neighbourhood.

“Many of those units are in high-needs areas; some are in Charleswood, south St. Vital,” said U of M community health sciences Prof. Randy Fransoo. “The influence of the environment around you is helpful — where social housing is located is not irrelevant.”

Fransoo and Brownell said being in a class full of high achievers planning to go to post-secondary school can encourage students from more difficult backgrounds and make a difference in several ways. “High school completion is one of them, teen pregnancy is another,” said Brownell.

Graduation rates for children in social housing in a higher-end area is 63 per cent, in poor areas it’s 26.5 per cent. Teen pregnancy for social-housing children is 67 per cent higher in low-income neighbourhoods.

A federal experiment with a guaranteed annual income in Dauphin in the 1970s has become near-legendary with social researchers.

Fransoo said when the U of M’s Evelyn Forget studied the Dauphin guaranteed annual income project, she found enrolment in Grade 11 was 110 per cent of Grade 10, showing some had returned to school. There was lower hospitalization in the community, he said, while there was less demand for help from multiple overburdened agencies.

And now that we’ve solved health care, what about the failures of public education, which in Manitoba have come to mean the gnashing of teeth every three years when the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development or the Council of Ministers of Education in Canada conduct extensive testing?

Forget that the OECD testing of the industrialized world shows Manitoba children outperform most of the developed world in math, reading and science, because no one critical of our education system pays that the least bit of never mind.

Manitoba children have been consistently at or very near the bottom among Canadian provinces in the last few rounds of testing — last year’s randomly chosen 15-year-olds will see their OECD test scores in December.

Seven Oaks School Division superintendent Brian O’Leary and U of M education Prof. Jon Young argue in the journal Education Today that public wailing over what has happened should give way to getting to the kids before they fail. They call it — jargon alert — leading and trailing indicators.

Essentially, they see the keys to intervention are to reach kids before the end of Grade 3, and among older children, to prevent them from failing Grade 9 credits.

Testing data arrive too late to help struggling students, they wrote.

“While the media and politicians may pay more attention to these high-profile, narrowly focused, comparative data sets, educators and parents may be better served by focusing more of their attention on developing and sharing leading indicators,” said O’Leary and Young. “We know that if a child isn’t reading well by the end of Grade 3, they will struggle throughout their remaining school years. They help us know what we should focus on.”

‘Failing to pass even a single Grade 9 course and having to repeat it with students who are a year younger is highly predictive of failing to graduate. With this data, we have the opportunity to provide extra help, opportunities to complete missing work, or a chance to complete the work in summer school,” said the two scholars.

Meanwhile, good luck getting parties to take a position on testing kids throughout the K-to-12 system, which is anathema to the NDP and to the Manitoba Teachers’ Society.

Two educators eager to test are University of Winnipeg math Prof. Anna Stokke and Jamie Wilson, who before becoming Treaty Relations Commissioner in Manitoba was education director at Opaskwayak Cree Nation.

“If you have tests in place, and they show things aren’t working, you adjust,” said Stokke. “We have no check measures. Just make a good test that tests outcomes — it takes a period.”

She said Manitoba’s curriculum started to go downhill in 1996 when it dropped fractions — under the Tories — and in 2006 when times tables disappeared under the NDP. “The curriculum up to 1996 was a really good curriculum. Kids learned fractions in Grade 4, now it’s grades 7 and 8.

“Who makes these changes? Consultants. There’s a whole layer of people who make curriculum. Education fads — it’s just a fad,” Stokke scoffed. “If you look at a provincial test a kid wrote in 1985, it was phenomenal. If you gave that test to a kid in Grade 6 now, no way; they wouldn’t have learned half the material.”

Echoed Wilson: “I like those rigorous high expectations. The measurements aren’t going to be good, but man, we’ve got to face it. Measurement is key — we’ve been reluctant to even have that dialogue.

“The best-performing schools I’ve seen take full responsibility (and say), ‘Let’s do something about it,’” Wilson declared.

nick.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Nick Martin

Former Free Press reporter Nick Martin, who wrote the monthly suspense column in the books section and was prolific in his standalone reviews of mystery/thriller novels, died Oct. 15 at age 77 while on holiday in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.