Kill and be killed

Headingley Gaol Cemetery final resting place for those who swung from the hangman's noose

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/08/2016 (3435 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

HEADINGLEY — At the Headingley Gaol Cemetery, it’s a struggle to feel the sympathy and respect one usually has at a burial ground.

The men here are all buried for a single reason: they murdered and were executed for their crimes.

Take Peter Piniak. In 1933, Piniak, 26, killed Martha Squarok, a nearby neighbour.

Squarok had apparently been going around telling everyone Piniak was to blame for his baby’s death. Squarok claimed Piniak let the baby freeze to death.

Piniak went over to her house to have it out with her, and, on her doorstep, smashed her head in with a piece of firewood.

He then claimed the life of Squarok’s five-year-old son, Eddie, by throwing him down a well.

Another burial is of George Jayhan, a heroin addict who was robbing Winnipeg pharmacies in 1934. Jayhan would produce a revolver, force the pharmacist in back, tie him up, then make off with narcotic prescription drugs. He was described as dangerous because he was so jumpy, probably due to being strung out all the time in need of a fix.

During one morning robbery, just before the Norbridge Pharmacy on St. Mary’s Road opened, Jayhan tied up the proprietor in back like usual. But when he went to the front to get drugs and money from the cash register, a delivery boy walked in. So Jayhan trooped him to the back and tied him up, too. Then the first customer walked in. Jayhan went through the same routine.

Meanwhile, a young boy passing the pharmacy saw what was going on and had a service station attendant phone police. The boy saw Jayhan leave so he and four friends went into the pharmacy to investigate. But Jaydhan returned moments later because he’d left behind his basket of narcotics.

Did you ever have one of those days? Jayhan would one day be telling fellow inmates. The boys were too many to tie up so Jayhan just ushered them into the back and told them not to move.

Long story short, the incident ended tragically for policeman Sgt. John Verne. Jayhan carjacked a vehicle and had a father and son drive him to Water Avenue. Sgt. Verne caught up with him there, and the two faced off behind the stolen vehicle. Jayhan shot and killed Verne with two bullets to the stomach.

Jayhan and Piniak belong to the select group of 16 prisoners who were executed at the Headingley Gaol gallows and buried here, just west of the penitentiary.

Executions began at Headingley Gaol in 1932 and ended in 1952 with the hanging of another cop killer, Henry Malanik. Canada abolished capital punishment in 1976.

In total, 25 men were executed on the scaffold at Headingley Gaol, now called Headingley Correctional Centre. In the case of 16 of them, the bodies went unclaimed by friend or family. So the gaol buried them.

It was the law at the time. Section 1071 of the Criminal Code required executed offenders be buried within a penitentiary’s walls.

The Headingley gallows was pretty active in the 1930s with 15 hangings, only six in the 1940s, and four from 1950-52.

The execution chamber still exists, and is the last standing permanent gallows in Canada.

It’s in fine running order, too. In 2004, guards assigned a troublesome prisoner to restore the gallows in order to channel the energies constructively.

It worked. Glenn Glays, behind bars on an 18-month sentence for arson endangering life, had carpentry skills, and putting them to work had a calming effect on him. “This is what I like doing,” Glays told a newspaper reporter at the time. His work included everything from removing dung left by pigeons, to reinstalling the trap doors.

Gallows are basically a beam with a noose and a trap door. Gordon Harding, a retired correctional officer, recalled last week the gallows were on the main floor, and the trap door opened to a small chamber in the basement.

You enter through a steel door. However, there are no scaffold steps to climb, like in the Western movies, said Harding. A trap door would open like a chute, pulled by powerful springs, and the prisoner’s neck would snap from the drop. “A doctor would go below and check his chest and make sure he was taken or not,” said Harding. The death sentence still existed when Harding started work there but the executions had stopped.

One of the oddities of the gallows was the rope left a burn mark on the wooden beam every time it was used. “You could see every burn mark from the drop. Some of those guys were a little heavy, and there must have been a little slack in the rope. So when it tightened, it just burned the beam,” said Harding.

The unclaimed corpses were originally buried in a small cemetery within the penitentiary walls, near the Assiniboine River. Too near, as it turned out. By the 1970s, caskets were starting to slide into the river.

“The riverbank was caving in,” explained John Heaps, 83, a correctional officer at the time. “Ice would come down in spring and cut out the bank. It washed away the bank and the caskets were starting to show.”

The graves of those executed had to be moved. So the pentitentiary secured a small plot of land in a farmer’s field just to the west, and proceeded to relocate the graves. That was in about 1970, said Harding. “They kept it very quiet,” he said.

Farmers were harvesting in the field when I visited. The mosquitoes were so bad it didn’t leave much time for meditation, or conjuring up anything resembling sympathy. The mosquitoes were so thick I was slapping two at a time.

A chain link fence marked the cemetery. There is no signage. There is only a large wooden cross made out of four-by-four lumber, flaking its white paint. Corrections staff cut the grass regularly.

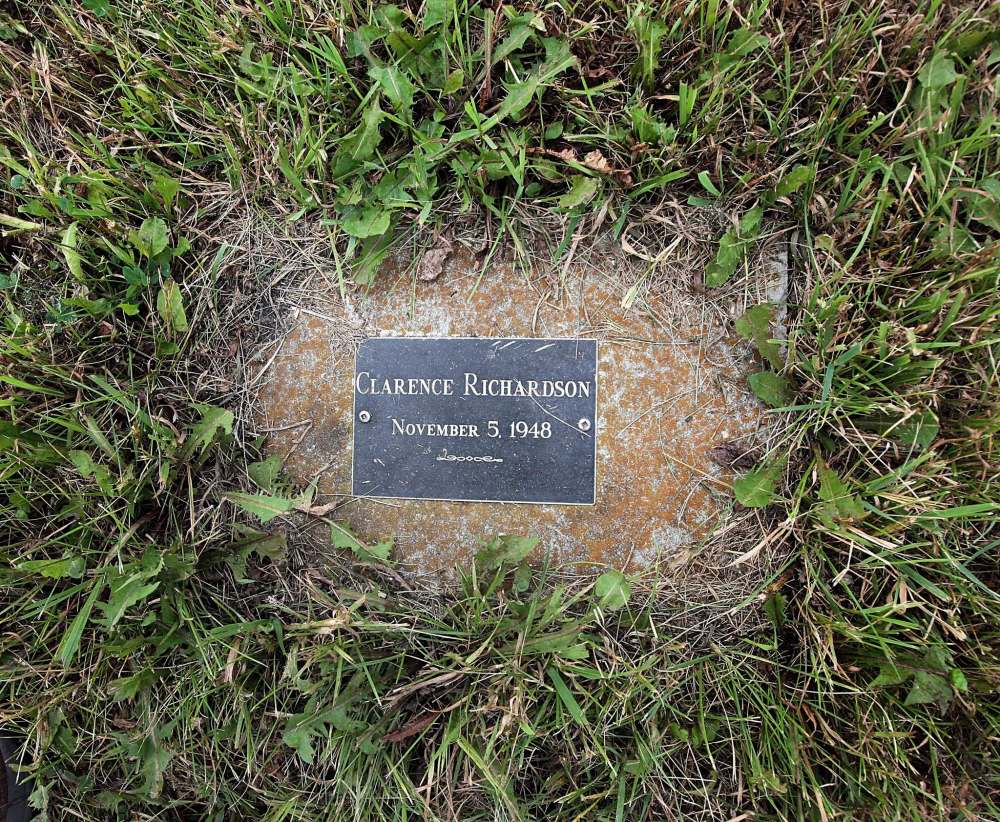

The grave markers are foot stones made of concrete, with a contrasting black plaque providing the barest of details: the deceased’s name and date of execution.

Not surprisingly, most of their victims were women. The story of Walter Stoney, hanged in 1951, is not atypical. His victim was Martha Perreault, a mother of six. He stabbed Perreault 18 times during a drinking session in his room at the National Hotel near Higgins Avenue.

Headingley conducted a triple-hanging on Feb. 16, 1939. Peter Korzenowski, William Kanuka and Dan Prytula were all hanged for their roles in the murder of 81-year-old Anna Cottick of Gilbert Plains. Cottick and her husband were attacked as they slept in their farmhouse, on May 13, 1938.

Kanuka was the only one choosing to speak when the guilty verdict came down. “I did not enter the house, and I killed no one, and I do not think I should be hanged,” he said.

The families of the executed refused to claim their bodies, so all three were buried at Headingley.

One of the juiciest stories is that of Clarence Charles Richardson, who murdered his married mistress.

Anne Vardy was discovered buried under a heap of snow along St. James Street on Jan. 2, 1948. Her skull had been fractured, struck at least eight times with a hammer.

Initially, Richardson denied Vardy was ever in his truck. He claimed he was driving to Selkirk on Jan. 2 and happened to see her and a man pushing a taxi cab out of the snow near Middlechurch.

Richardson’s story quickly fell apart. It was known that he and Vardy had an affair earlier, although Richardson claimed it was over.

Vardy wasn’t his only lover. It was found he also had a girlfriend overseas in Germany he met while in the service.

Richardson wasn’t Vardy’s only lover, either. Vardy was married to an electrician but obviously they lacked electricity together. She also had a boyfriend at the bowling alley with whom she’d become pregnant.

By trial’s end, Richardson’s lawyer conceded his client murdered Vardy, but claimed he had amnesia and wasn’t responsible for his actions.

The prosecution said if he’d lost any memory, it was only for those actions he wanted to forget. If he had amnesia, why did he remember the concocted story of seeing Vardy pushing a stalled taxi cab? And how was he able to repeat that story several times?

Guilty. He was hanged Nov. 5.

The gaol cemetery can be found by turning south at the brown Principal Meridian sign, west of Headingley Correctional Centre on Highway No. 1, onto a dirt road. The cemetery becomes quickly apparent.

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Monday, August 29, 2016 7:00 AM CDT: Adds photos

Updated on Monday, August 29, 2016 11:53 AM CDT: Adds more photos

Updated on Monday, August 29, 2016 5:26 PM CDT: Corrects typo.