Time for Canada to take off its costume

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/09/2019 (2296 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Halloween draws near. For those of us in the Indigenous world, this means we will field many questions about Indigenous-themed costumes.

We’ll be interrogated about the worst of them — “Pocahottie” or “Warrior Chief” come to mind — and be forced to recount why stereotypes are harmful, offensive, and lead to violent behaviour, especially among children.

We’ll explain these costumes are simplistic and rely on objects, weapons, and face paint to make one appear racialized when they’re simply a performance of fantasies, fears, and desires.

And, finally, we’ll be asked whether it’s OK for non-Indigenous people to dress up as Indigenous people.

I’ll give my regular answer: “Costumes don’t represent Indigenous peoples, they represent the ideas non-Indigenous peoples have about them.”

Stereotypes have been necessary for nations such as Canada and the United States to demonize and demean Indigenous peoples and, as a result, take the land, remove their children, and impose laws to make it all “legal.”

Indigenous-themed costumes aren’t just fun and games, they’re a method society uses to control Indigenous peoples.

The issue isn’t just Halloween. When you ban one costume or store, for example, another shows up the next day. Dressing up as an “Indian” takes place everywhere: at sporting events, in movies, novels, on fashion runways.

The issue is much larger. Stereotypes reside in the way an entire society views Indigenous peoples.

I’m therefore far more interested in the people who buy Pocahottie and Warrior Chief than the people who sell them.

“Costumes don’t represent Indigenous peoples, they represent the ideas non-Indigenous peoples have about them.” – Niigaan Sinclair

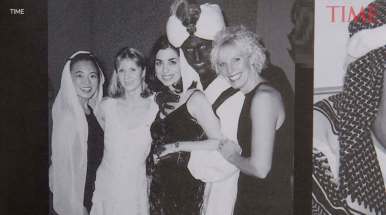

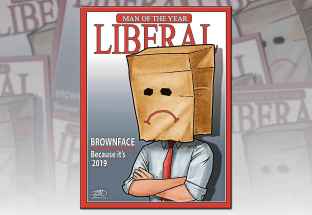

Which brings me to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who this week faced questions for photos and a video showing him dressed up in blackface and “brownface” three times (the latest being in 2001).

“I take responsibility for my decision to do that. I shouldn’t have done it. (I) should have known better. It was something I didn’t think was racist at the time, but now I recognize it was something racist to do. And I’m deeply sorry,” Trudeau told reporters Wednesday night.

On Thursday, in Winnipeg, Trudeau admitted there may be more instances, but he “doesn’t remember.”

“I think the question is, ‘How can you not remember that?’ The fact is, I didn’t understand how hurtful this is to people who live with discrimination every single day. I have always acknowledged I come from a place of privilege, but I now need to acknowledge that comes with a massive blind spot.”

I credit Trudeau here.

One’s privilege is difficult to analyze and speak publicly about. As a heterosexual, male, able-bodied, Christian, cisgender man whose father was the prime minister of Canada, Trudeau literally inherited overwhelming benefits.

As someone who was surrounded by the exclusion and exploitation of society’s most marginalized, no one should be surprised he failed to consider how dressing up in blackface would be demonizing, demeaning, and inflict violence on racialized people.

If people want to judge Trudeau for who he was — or perhaps still is — that’s up to them. I suppose that will be decided in the federal election next month.

If he wins, it’s not like Canada hasn’t before had a prime minister with a history of privilege and track record of benefiting from racism. (Pretty much all of them.)

For the record, I am encouraged Trudeau is admitting to his privilege and naming his actions racist — because they are.

But before Canadians pass a grand judgement on him, I’d point this out: Trudeau didn’t dress up for himself. He was in a public setting, surrounded by Canadians who were doing the same thing and having a great time.

And no one stopped it.

To be clear, this was not the responsibility of the two (presumably) Sikh men posing for a photo with Trudeau in 2001. It is never the responsibility of racialized people to teach others stereotypes about them are harmful. Victims are not guilty for their abuser’s behaviour.

So, now that we are beginning to understand privilege and power are intricately intertwined, resulting in laws and practices that demean and dominate racialized people, what are Canadians going to do about it?

I’m speaking here about the hundreds of Canadians dressed up in costumes and face paint joining Trudeau in his “blind spot.”

These are privileged, everyday Canadians demeaning others and smiling. And no one did anything about it.

In fact, no one said much about any of this for nearly 20 years.

The silence speaks volumes. It voices a collective consent to racism and participation in it this country cannot ignore.

Trudeau wasn’t alone in his blackface and “brownface” costumes — he was a mirror to the nation he would soon lead.

So, now that we are beginning to understand privilege and power are intricately intertwined, resulting in laws and practices that demean and dominate racialized people, what are Canadians going to do about it?

Have a conversation — a hard and difficult one?

If so, it begins by acknowledging this country’s long history of privilege and harms, and how so many benefit from this violence.

Then, the hard work begins. Then we can take the brave step of changing our laws, practices, and behaviour.

This is not easy. It involves a lot of humility, patience, and time. But this is how a country disrupts dysfunctional cycles, grows, and steps into the future.

This is how a society looks in the mirror, realizes the costume it’s wearing is wrong and takes off the face paint.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, September 21, 2019 9:02 AM CDT: Fixes typo.