Turning point for learning

Studies show in Winnipeg School Division, Grade 8 is when students are either on track for graduation, or going off the rails

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/01/2024 (741 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

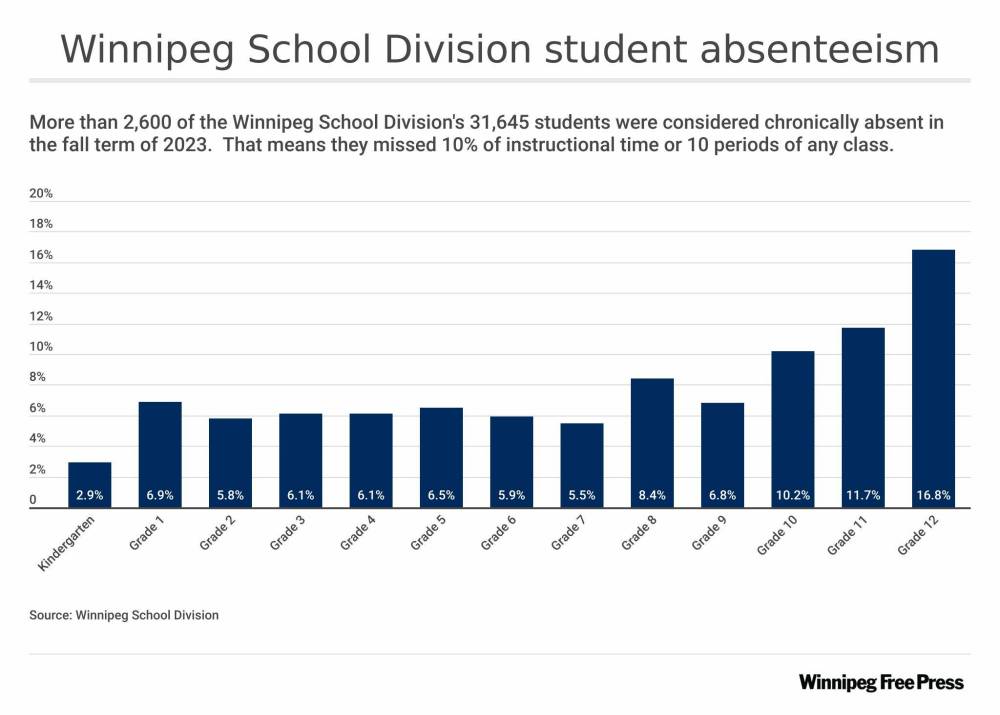

A new analysis of attendance in the Winnipeg School Division shows Grade 8 marks a turning point for students, while more final-year students are missing class regularly than peers in younger grades.

Manitoba Education introduced updated monitoring and reporting requirements to enhance student presence and engagement at the start of the school year.

“Chronic absenteeism” is defined as unexcused absences accounting for 10 per cent of instructional days in kindergarten to Grade 8 and 10 classes in a single high school course.

More than eight per cent of the student body in WSD — the largest school division in the province, with a K-12 population of about 31,600 — met that threshold in the fall.

“We’re ripping the Band-Aid off on our data and saying that we’ve got a problem,” WSD chief superintendent Matt Henderson told the Free Press.

Henderson said the division is releasing its “deep dive” into truancy to acknowledge the issue and share efforts to re-engage children and families, from putting suspensions under a microscope to piloting no-fee lunch supervision in elementary schools.

“We don’t talk about ‘at-risk’ kids anymore. We talk about kids being on-track or off-track for graduation and that really puts the onus back on the teachers, (principals and division leaders),” he said, noting the recent findings will be largely unsurprising to educators.

WSD staffers reviewed absences, excluding sick calls and appointment-related leaves, between the start of the 2023-24 school year and the end of November.

A total of 2,644 students were deemed chronically absent. The largest share of those learners — almost 17 per cent — are in Grade 12.

The data indicates spotty records start to balloon in middle years and although there is an improvement in Grade 9, when many students transition to a semestered system, absenteeism worsens year-over-year throughout high school.

Henderson said the board office has asked schools to cross-reference the fall figures, which indicate truancy is prevalent in all corners of the division and ensure a teacher has reached out to every student who is “off-track.”

“We’re ripping the Band-Aid off on our data and saying that we’ve got a problem.”–WSD chief superintendent Matt Henderson

He noted that there’s a difference between getting a call from an administrator or a pre-recorded voice message versus picking up the phone and hearing a familiar voice: “It’s really an act of love, at that point, to say, ‘Just thinking about you, how do we get you back here?’”

The superintendent added many central schools are also reworking schedules to bring staff together more frequently — in some cases, by implementing late-start, early-dismissal days — to meet about specific students and strategies to draw them to class.

Poor mental health, bullying and caregiving responsibilities are among the numerous reasons students miss school. The COVID-19 pandemic added to that lengthy list, raising new concerns related to contracting the novel coronavirus and disruptions brought on by the digital divide.

Authentic and caring relationships are key to identifying the complex barriers imposed on students — be they systemic racism, food insecurity or otherwise — and learning how to advocate with them and their families, said inner-city teacher Alana Ollinger.

“Time is at the heart of all of this — time to get to know learners. This is a type of support that goes well beyond one semester and, at times, even one year,” said Ollinger, who works at Niiwin Minisiwiwag, an off-campus WSD site run in partnership with the Indigenous Education Caring Society.

Niiwin Minisiwiwag was designed to welcome teenagers and young adults back into the public school system, regardless of what disrupted their learning, and provide one-on-one academic tutoring, cultural programming and wraparound supports.

Reflecting on the alternative model, Ollinger said she and her colleagues try to create a space learners “can make their own” and ensure they see themselves and their identities represented in staff and curricula to foster a sense of belonging.

Since joining WSD in the summer, Henderson has touted the importance of making all schools “as sticky as possible,” so students jump out of bed in the morning and are in no rush to get home.

“Time is at the heart of all of this — time to get to know learners. This is a type of support that goes well beyond one semester and, at times, even one year.”–Alana Ollinger

The superintendent said, in practice, that looks like reaching out to community organizations such as Peaceful Village and the Winnipeg Aboriginal Sport Achievement Centre to scale-up extracurriculars in high schools.

WSD was unable to provide historic attendance data.

Henderson indicated part of the recent project involved clarifying how to collect statistics and monitor them going forward.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., she first reported for the Free Press in 2017. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.