Probe flags troubles in literacy education

Findings cite lack of evidence-based teaching methods, long wait times for clinical assessments

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

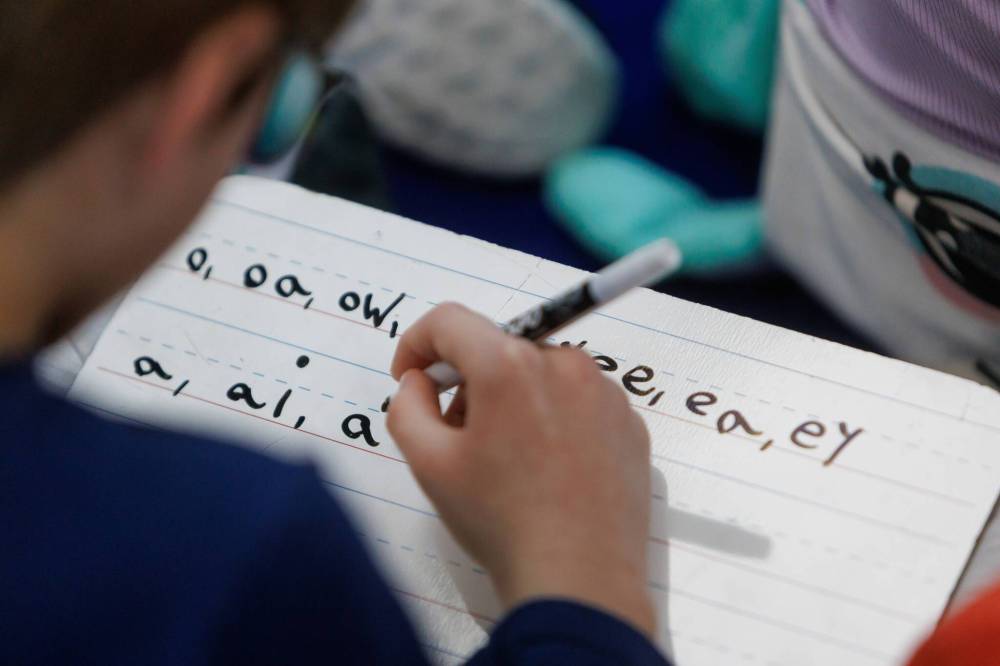

Human rights investigators have found that parents of struggling readers across Manitoba are being forced to take on “a full-time job” of advocacy so their children can become literate in local public schools.

The Manitoba Human Rights Commission released the long-awaited findings of its probe into literacy 101 education on Thursday — the penultimate day of Dyslexia Awareness Month 2025.

The 70-page document reveals that many schools are not using evidence-based methods to teach reading and lengthy wait times for clinical assessments are affecting overall literacy rates.

The results are unsurprising for Laura Jones, a mother who volunteered at the launch event organized in partnership with Dyslexia Canada.

Despite reporting concerns about her youngest’s reading struggles and the best efforts of teachers, Jones said her now-Grade 5 daughter was unable to participate in silent reading periods last year.

“She’d hold the book up to her face and sit there the entire time and feel stupid because she wasn’t actually reading and she didn’t know how,” the mother of two said. “It was really impacting her confidence.”

Her youngest child only disclosed the severity of her struggles after a 2024 meltdown in an ice cream shop. She was unable to read the menu and embarrassed because all of her friends could, Jones said.

The Old St. Vital resident noted she’s lucky to live in a public school division that has already begun overhauling instruction to prioritize back-to-basics phonics to align itself with neuroscience on how children become readers.

But the Louis Riel School Division still did not catch her daughter’s issues, let alone put her on a waitlist for an assessment. The Jones family paid for private services. Her daughter was diagnosed with dyslexia.

The MHRC report’s authors are calling for a societal shift to address chronic “attitudinal barriers” that negatively affect how many children seek help, as well as the effectiveness of both interventions and accommodations.

The commission has issued eight recommendations to help make that happen.

“We heard from parents, over and over again, about the amount of sacrifice that they’ve had to undertake,” said Megan Fultz, a lawyer who works at the commission and co-wrote the report.

“It was so overwhelming to hear about.”

“We heard from parents, over and over again, about the amount of sacrifice that they’ve had to undertake.”

More than 200 people showed up to hear project co-leads Fultz and Karen Sharma discuss their takeaways, following on four years of research, at the Centre Culturel Franco-Manitobain.

Sharma told a packed auditorium the feedback she’d heard and read over the last 36 months will stay with her “for the rest of my life.”

The report includes direct quotes from students who participated in online surveys and public hearings.

Students described feeling “dumb,” “in trouble” and having to work so much harder than their peers for whom read-aloud activities do not cause crippling anxiety.

“I’ve just stopped going to school,” one young participant said.

“Messages like those really underscored for us the criticalness of looking at this issue, and being committed to systemic change,” said Sharma, executive director of the commission.

Her office launched a special project on human rights issues affecting students with learning disabilities in October 2022.

Co-leads Sharma and Fultz announced this week that they are releasing two different reports.

The Phase 1 report, Supporting the Right to Read in Manitoba: The ABCs of a Rights-Based Approach to Teaching Reading is now online at wfp.to/iX7.

It was delayed multiple times, much to the frustration of parents on waitlists for school-based assessments to determine why their child is struggling and those paying costly fees for private tutoring.

The commission repeatedly cited an influx in human rights complaints as large and related workload challenges.

Sharma spoke on Thursday night about the urgency of making changes to status-quo screening for early signs of struggle with reading.

Struggles worsen if they go unaddressed, she said.

Also Thursday, Fultz told the crowd the report’s authors had come to the conclusion that every child can learn to read. It’s ableist to suggest otherwise, the lawyer said.

The project was nicknamed Manitoba’s Right to Read — a nod to the title of an eastern counterpart’s groundbreaking inquiry on the same topic.

“I want to see more strength and teeth behind the directive and something that will be long-lasting and won’t shift with political shifts.”

The MHRC drew on Ontario’s winter 2022 deep dive into the neuroscience of reading, as well as findings that its public schools were not using evidence-based practises to teach children basic literacy skills.

The co-authors indicated they also benefited immensely from Saskatchewan’s 2023 exposé on gaps in literacy education in that province.

Jones said she’s concerned Education Minister Tracy Schmidt’s new directive to divisions to implement universal screening for learning disabilities is insufficient on its own to make meaningful change.

LRSD, where her youngest is enrolled in Grade 5, is already doing these rapid tests and teachers failed to recognize her daughter had dyslexia, she noted.

“I want to see more strength and teeth behind the directive and something that will be long-lasting and won’t shift with political shifts,” Jones said, adding that could be in the form of Bill 225 (The Public Schools Amendment Act — Universal Screening for Learning Disabilities) or something else.

A spokesperson for Schmidt’s office confirmed Friday the minister is reviewing the commission’s newly released recommendations.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., she first reported for the Free Press in 2017. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.