Building a better city

Reducing suburban sprawl huge step toward shrinking carbon footprint

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/12/2015 (3690 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Rio de Janeiro, Kyoto, Copenhagen and Paris… it reads like a great bucket list of travel destinations, but these cities are more significantly connected as hosts of high-profile global climate change conferences.

From 1992 in Brazil to last week in France, the nations of the world have repeatedly come together in exotic locales to negotiate agreements for reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The general pattern of results has been: set emissions targets, ignore them, set easier emissions targets, ignore them, and repeat.

With an increased recognition that the environmental clock is ticking, there is hope the Paris climate conference is the one that ends the cycle of inaction.

As one of the top-10 GHG emitters in the world, Canada came to France pledging a 30 per cent reduction of 2005 levels by 2030. Partnering in the effort to finally achieve significant reductions, individual provinces have come forward with their own targets — including Manitoba, where emissions are planned to be cut by one-third over the same period.

Canadian provinces with coal-generated electricity, large manufacturing industries or oilsands extraction are able to focus on these heavy emitters to find their reductions, but in hydro-powered Manitoba no single sector is a dominant GHG producer. To achieve its goals, efforts will need to consider a range of targets across different sectors, each contributing to the whole.

The buildings residents inhabit, directly and indirectly have the greatest single impact on Manitoba’s current carbon footprint.

Collectively, the heating and cooling of these structures represent 23 per cent of Manitoba’s total GHG emissions. Reducing building energy use will be an important step toward realizing environmental commitments. For many years, Manitoba’s low hydro rates and resulting long payback periods have made the capital investment in sustainable construction technologies difficult to justify for many building developers.

To overcome this, Manitoba recently became one of the first provinces to adopt the new National Energy Code for Buildings. This code makes high energy performance a mandatory requirement through such measures as increased insulation and restrictions on the number of windows. The goal of the code is to improve the energy efficiency of new buildings by more than 25 per cent and reduce GHG emissions to the equivalent of removing 90,000 vehicles from the roads.

How we construct our buildings is an important factor to climate change, but it may be even more important to consider where we construct them. In Canada, we have for a half-century built sprawling, low-density suburban cities — a form that has a profound effect on GHG emissions today.

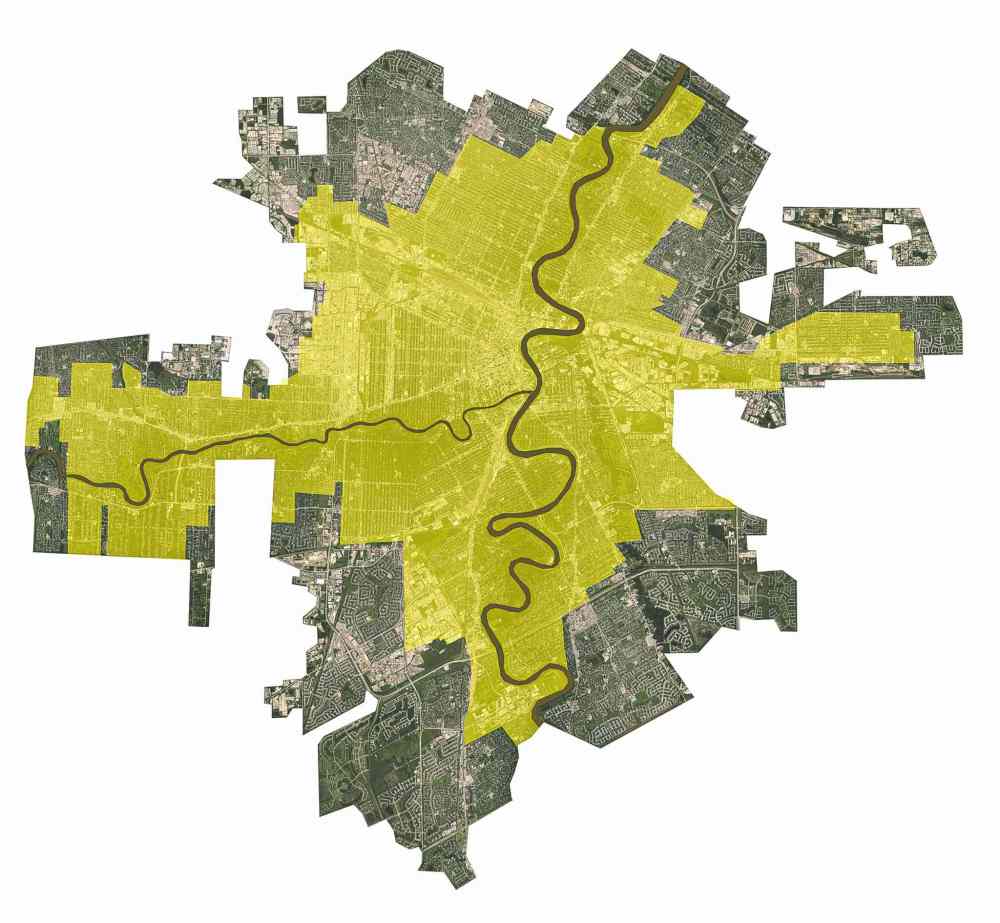

Winnipeg, as an example, has had the vast majority of its modern growth accommodated in very low-density suburbs that have disproportionately pushed the edges of the city farther from its centre. Since 1970, Winnipeg’s population has increased by roughly one-third, but its built area has grown by more than twice that amount, resulting in a significantly less-dense city overall.

With more than eight out of every 10 Winnipeggers now living in a car-dependent suburb, our lives have become centred on the automobile.

As commuting distances have grown, the car has become the only transportation option for almost all daily pursuits. Neighbourhoods are no longer designed around corner stores, libraries, churches, community clubs and schools. Most of these activities are now provided through the big-box model, requiring long travel distances accessed almost exclusively by car. A telling effect of this urban form is only 28 per cent of children walk to school, when in their parents’ generation, that level was almost 60 per cent.

The pervasive reliance on automobiles and the fossil fuels that power them has made the transportation sector the highest GHG emitter in Manitoba, responsible for 38 per cent of the total. Almost two-thirds of this comes from light cars and trucks. As our city sprawls farther, forcing us to drive even more, these numbers will only rise.

Many studies have found a direct correlation between a city’s density and its overall GHG emissions. A comparison between Canadian and higher-density European cities highlights this effect.

Car-ownership levels in western Europe and Canada are similar, but driving habits are significantly different. The higher-density, more compact layout of European cities results in shorter travel distances that often make walking, cycling and public transit use a more efficient option for day-to-day activities. Shorter commuting distances mean when urban Europeans drive, they drive for less time. These differences combine to create a less car-dependent lifestyle that results in Europeans consuming almost 50 per cent less energy per capita through automobile use alone, compared to Canadians.

In addition to burning more gasoline, sprawling Canadian cities also produce higher emissions through such things as the construction of larger roads, pumping water and waste over greater distances, building new community facilities and operating far-reaching civic services such as snow clearing and garbage pickup. These factors result in many North American cities having more than twice the emission levels of European counterparts.

Closer to home, corroborating studies in Toronto have shown residential emissions in dense, inner-city neighbourhoods with high-quality public transit systems are up to 10 times lower per capita than those in the sprawling distant suburbs.

Despite this unsustainable car-dependent lifestyle, cities such as Winnipeg continue to sprawl without control.

While facing extreme infrastructure deficits and crumbling streets we continue to borrow billions of dollars to build bigger roads in a short-sighted effort to reduce congestion. Long term, these roads become the catalyst for even more sprawl, traffic and car dependency as increased vehicle capacity promotes greater development further away.

The new federal government has promised to invest heavily in the infrastructure of Canadian cities. If the investment is done intelligently, this policy can work in lockstep with environmental targets. Instead of paying for new, larger roads, repairing what already exists and increasing investment in transportation initiatives that promote density will go a long way to reducing Canada’s carbon footprint.

An example of this is rapid transit, which not only provides a commuting option to private vehicles, it can be used to target locations for urban infill development around lines and stations.

Creative infrastructure investment can support downtown-renewal initiatives, infill development in mature neighbourhoods, higher-density new suburbs, as well as opportunities to redevelop former industrial lands and rail yards into infill communities.

Cities such as Winnipeg don’t have to be Manhattan to have an appropriate density. Simply setting a target of returning the city to 1970s density levels would have a profound impact on GHG emissions, taxes, road conditions, city services and quality of life.

With 80 per cent of Canadians now living in cities, the only way to meet our environmental commitments is to reconsider how we construct buildings and where we locate them.

Suburban sprawl began when energy was abundant, inexpensive and without environmental concern. Conditions have changed. Building cities that are higher-density, less automobile-reliant and more compact will not only help save the world — it might allow our children’s children the opportunity to walk to school one day.

Brent Bellamy is creative director at Number Ten Architectural Group.

bbellamy@numberten.com

Brent Bellamy is creative director for Number Ten Architectural Group.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.