Century of progress

Much has changed in the 100 years since Manitoba women secured the right to vote, but 'there is still work to be done'

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/01/2016 (3597 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

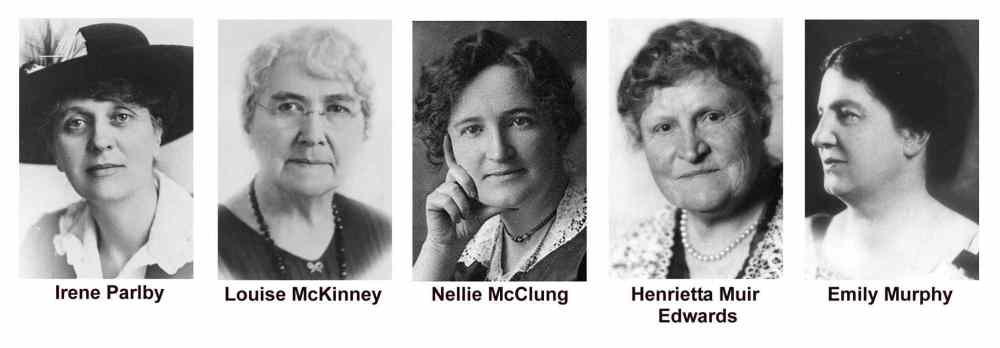

OTTAWA — Almost a century after Nellie McClung pushed Manitoba to become the first province to allow women to vote or run for office, she would have been pretty proud of what women have achieved, says her granddaughter Marcia McClung.

But she also probably would have been a little disappointed to see women have not achieved true equality, be it in the workplace, the political world or even in many families.

Although Nellie McClung dreamed that if women could secure the right to vote, all the other rights to become equals with men would surely follow, she knew when she died, in 1951, that had not happened.

“She did acknowledge there wouldn’t have been any progress without the vote,” Marcia said in an interview with the Winnipeg Free Press. “It was a really significant step.”

McClung, one of the most well-known leaders of the suffrage movement in Canada, did not really set out to secure the right to vote. She, like other suffrage leaders, was drawn to it out of her work on other issues. Marcia says McClung was particularly concerned with horrible labour conditions for child workers, and was also influenced by her mother-in-law, who was the president of the Manitou chapter of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

Veronica Strong-Boag, a professor of history at the University of British Columbia and the general editor of a seven-volume series on women’s suffrage and social justice in Canada that will be published in 2017, said the temperance movement was closely aligned with the suffrage movement because many saw they weren’t going to get anywhere on the former without gaining the latter.

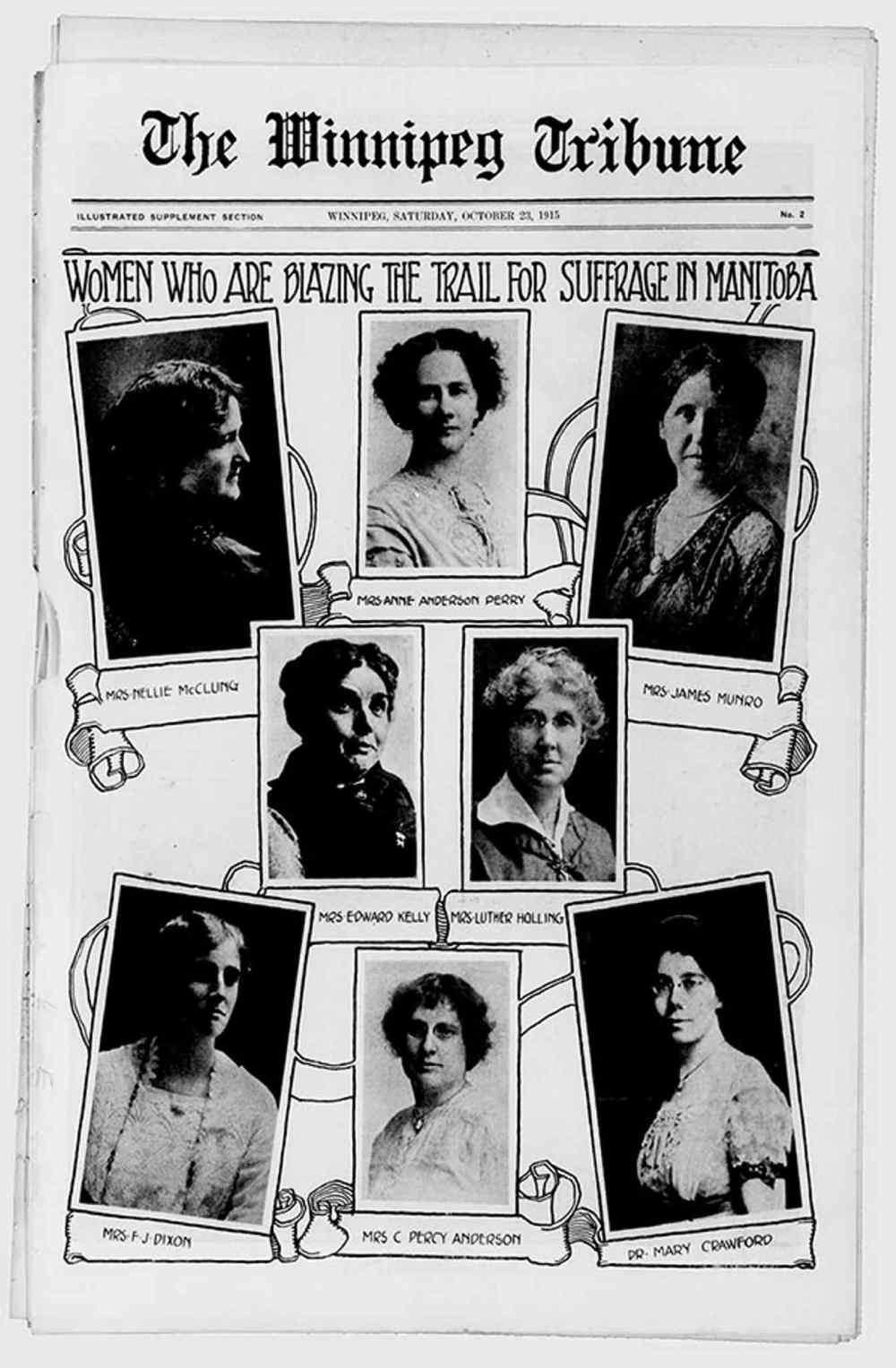

Strong-Boag says most of the suffragists were middle-class women, dominated by farmers and professionals, including author McClung, journalists E. Cora Hind and Lillian Thomas and Dr. Amelia Yeomans.

The history of the vote in Canada is not just a women’s issue.

During the time of British North America before Confederation, and for nearly a century afterwards, the only group of people who were never disenfranchised were white, Protestant, wealthy men. At various times, the vote was withheld from women, Catholics, Hindus, Chinese, Japanese, Indo-Canadians, indigenous people, Mennonites, blacks and the poor.

But the women’s suffrage movement was the most widespread and well-organized franchise in Canada.

Prior to Confederation, there were some examples of women being allowed to vote if they met the property-owner requirements, particularly in Lower Canada, where French civil law prevailed. However, by the 1850s, all the provinces in British North America had passed laws barring women from voting.

Between Confederation in 1867, and the early parts of the 20th century, different governments passed varying laws about voting eligibility. Some provinces barred public servants from casting ballots, others prevented voting based on race or class. Nova Scotia didn’t allow people to vote if they were on social assistance. British Columbia ruled out voting for people convicted of treason or other serious crimes.

After Confederation, additional laws were passed preventing other groups from voting, and the eligibility requirements were different in each province.

The Franchise Act of 1885, which Sir John A. Macdonald touted as one of his greatest achievements as prime minister, unified federal voting rules for a time, limiting it to men, at least 21 years old, who were British subjects by birth or naturalization. Property-ownership requirements varied depending on whether you lived in a city, town or rural area. This law also prevented indigenous people and Chinese from voting.

It was during these latter years of the 19th century the suffrage movement began to take shape in Canada. Organizations such as the Women’s Suffrage Association and later the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association arose in Ontario in the 1880s. Many women began securing the right to vote in municipal or school board elections, starting in Ontario in 1884 and Manitoba in 1887.

But the big prize was enfranchisement at the provincial and federal levels, where women could affect change on divorce laws, custody rights and property rights.

In Manitoba, Margaret Benedictsson was leading a suffrage push among Icelandic women, and launched the Icelandic-language magazine Freyja in 1898 to publish stories about their issues.

A little over a decade later, McClung was among a group which founded the Political Equality League. The league’s members travelled the province to give speeches at town halls and country theatres.

McClung’s granddaughter says the barriers they faced were many, the opposition intense and the criticism sharp, yet they didn’t back down.

“There was something about that prairie grit,” Marcia said. “They were very undaunted, especially in those early years in Winnipeg with (premier Rodmond) Roblin, who was so patronizing.”

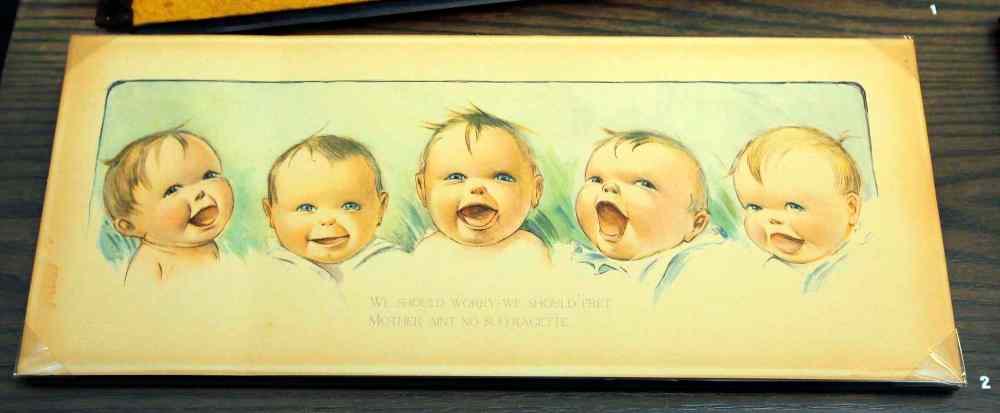

In January 1914, the group appeared at the Manitoba legislature to argue its case for women’s enfranchisement. Roblin dismissed them entirely, rejecting their arguments outright and telling them if women got to vote, it would break up families and “throw children into the arms of servant girls.”

This latter was particularly poignant for McClung who, as the mother of five children, constantly had to defend herself when she was out speaking at night and ensure crowds her children were fine.

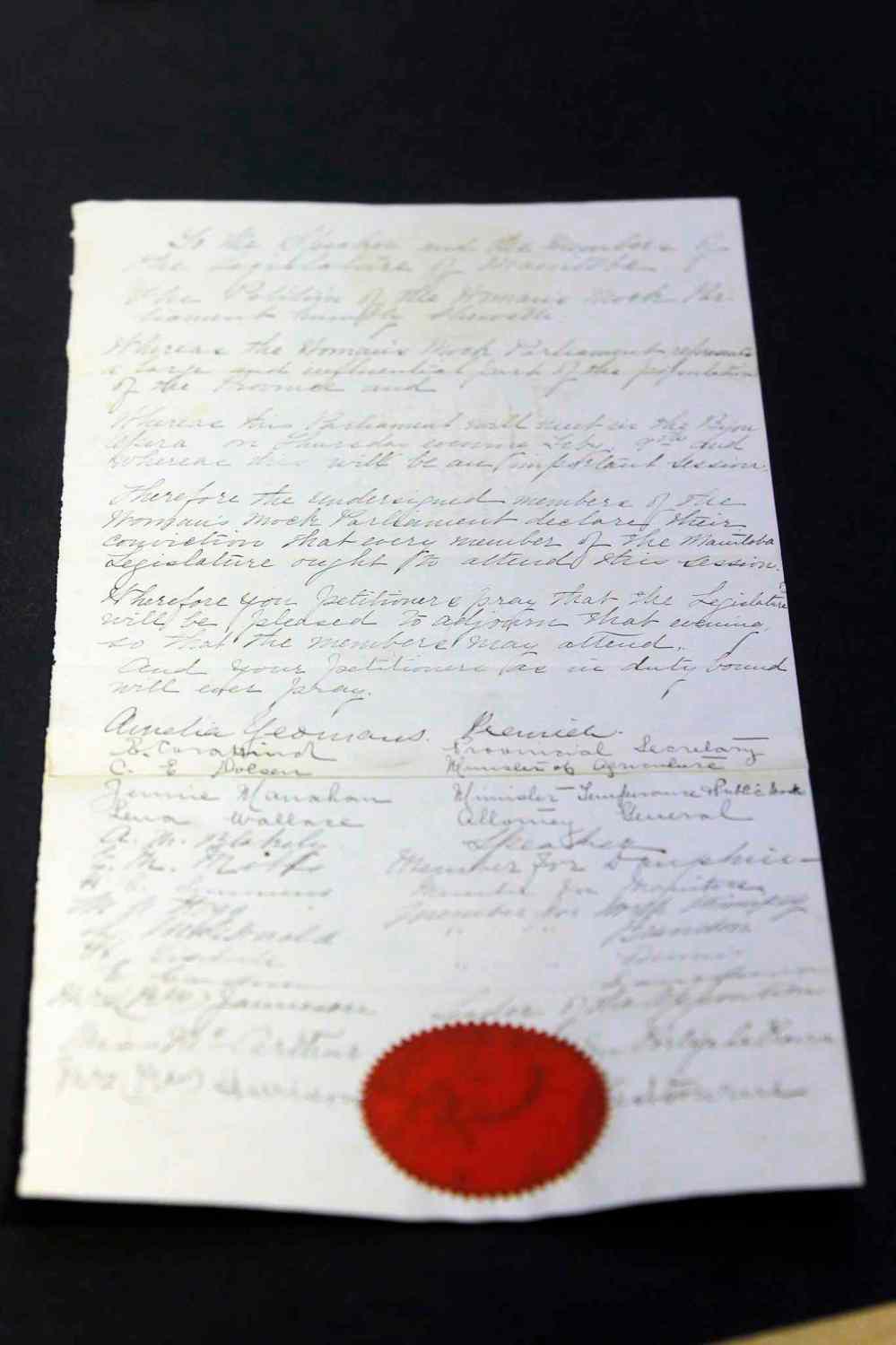

That same month, the Political Equality League staged the women’s mock parliament at the Walker Theatre in Winnipeg, ridiculing the arguments Roblin made against women’s suffrage by turning them around on men. The play, which was quite popular and performed in additional locations, was recounted in a Heritage Minutes TV spot in the 1990s as a pivotal moment in the suffrage era.

It was hoped the growing support for women’s enfranchisement in Manitoba would push Roblin to act, but it wasn’t until after he was defeated in the provincial election of 1915, and Liberal premier Tobias Norris elected, the government took action.

On Jan. 28, 1916, an Act to Amend the Manitoba Elections Act passed in the legislature, making Manitoba women the first in the country to be able to vote in a provincial election. A little over six weeks later, Saskatchewan followed suit; about a month after that, so did Alberta.

There was a domino effect across the country, with B.C. and Ontario granting women the vote in 1917, and every other province but Quebec doing so by 1925. Quebec would not allow women to vote until 1940.

Federally, prime minister Robert Borden began moving the needle on women voting in 1917, but only out of a need to gain support for his government’s conscription policy. His anti-democratic wartime election bills allowed him to rig the election in his favour by disenfranchising those unlikely to vote for him and allowing military votes to be distributed among ridings as he wished. Women were allowed to vote if they were in the military or had a husband, son or father who was. It wasn’t until 1918 that Borden introduced and passed a bill for universal women’s suffrage in Canada.

In 1920, property-ownership requirements were also discarded.

It would be many more years before universal suffrage was achieved for all groups.

In 1948, the federal government passed a law prohibiting race as a reason for excluding someone from voting, although it wasn’t until 1960 that indigenous people were allowed to vote in federal elections without giving up treaty rights.

Strong-Boag says while it’s true women may not have gained the kind of equality McClung dreamed of, gaining the vote did make a difference, particularly in the first decade afterward.

“We don’t have polls to prove it, but it’s quite clear the 1920s were incredibly fruitful for women,” she said.

The first women were elected to a provincial legislature in Alberta in 1917 and in Manitoba in 1920. Federally, Agnes McPhail became the first female MP in the House of Commons in 1921.

Laws were changed around divorce, child custody, property rights and minimum wages for women.

“This would not have happened but for the fact legislatures were looking at women voters,” said Strong-Boag.

In 1929, the Famous Five, including McClung and Emily Murphy, won the Persons Case, successfully convincing Britain to change the definition of person to include women, thereby opening the door for women to be appointed to the Canadian Senate.

The progress slowed almost to a halt with the Great Depression, as the economy forced attention away from progressive legislation.

It would be decades before women started being elected at any level in large numbers — and even in 2016, women still represent about one-in-four city councillors, between one-tenth and one-third of provincial legislators, and one-in-four MPs.

Women didn’t hit double-digits in the House of Commons until 1979, after which a slow creep upwards has been recorded. There were 88 women elected last fall.

Manitoba didn’t elect a single female MP until 1963, and to date has elected just 13 women in total.

Nationally, 315 women have been elected to the House of Commons since 1921.

In 1993, Kim Campbell briefly became the first female prime minister when she took over leadership of the Progressive Conservatives, but she would hold office for just 132 days before being defeated in the 1993 election.

There have been 10 female premiers in Canada, including three currently. Manitoba is one of four provinces yet to have a woman occupy the premier’s office.

Marcia McClung says one of the most common questions she gets from people who recognize her last name is: what would her grandmother would think of what is happening in the world today when it comes to women’s rights?

“It’s a hard question to answer,” says Marcia, who was just four years old when her grandmother died. “I think she would generally agree there has been progress on many fronts.”

She would, however, certainly have been quite proud of the attention being given in Manitoba to the 100th anniversary of its women getting the vote.

“She would have loved to see there was a recognition of the significance of this step, but she would remind us there is still work to be done.”

mia.rabson@freepress.mb.ca