Trump not the first outsider president

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/01/2017 (3219 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The United States presidential campaign had been mean-spirited. Supporters of each candidate hurled insults and made outlandish accusations, even going so far as to suggest the spouse of one contender had committed adultery and was a bigamist. The candidate regarded by his elitist opponents as uncouth, a hero of the mob and a “shameless and lawless gamester” emerged the victor.

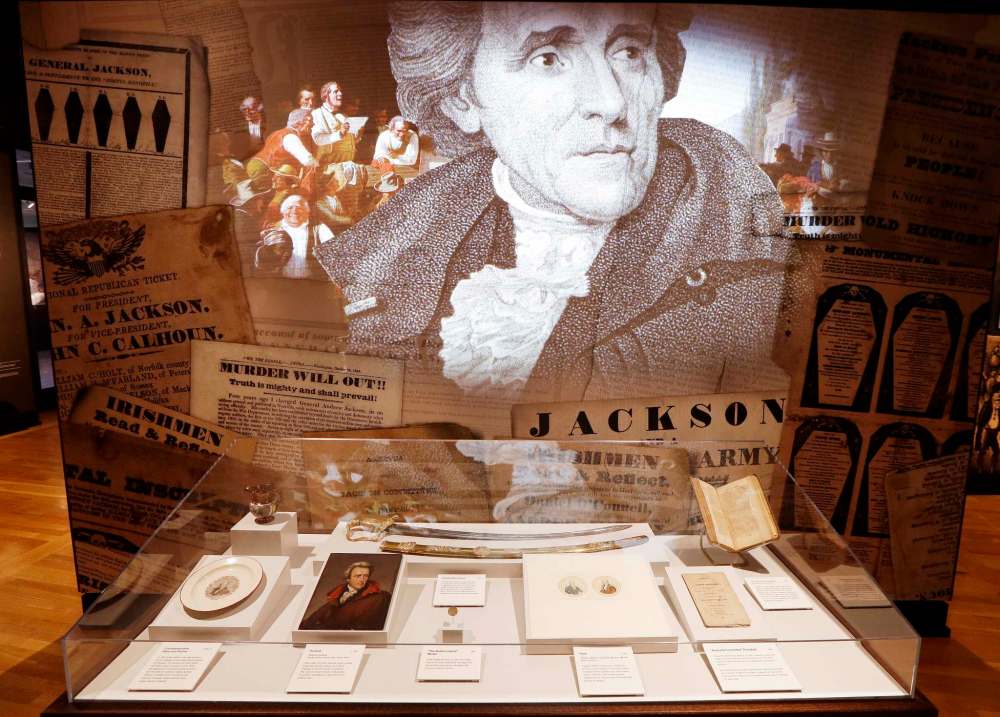

Sound familiar? This is not, in fact, a summary of what just transpired in the recent presidential campaign between U.S. president-elect Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton, which was as nasty. It was a recap of the presidential election of 1828, which pitted the incumbent, John Quincy Adams, against his archrival and the victor, Andrew Jackson, a hero of the Battle of New Orleans, the last great conflict of the War of 1812. On the field of battle, Jackson was said to have been as “tough as old hickory” wood and thereafter he was known by the nickname “Old Hickory.”

Adams represented the Democratic-Republicans, the anti-federalist faction that dated back to Thomas Jefferson, and Jackson was the candidate of the recently established Democratic Party. During the campaign, Jackson was constantly referred to by supporters of Adams as a “jackass.” Instead of being angry about it, Jackson embraced the label and promoted the notion that he was “strong-willed.” Political cartoonist Thomas Nast later used the donkey to symbolize the Democrats, and it stuck. He also came up with the elephant to symbolize the modern Republican Party, formed in 1854.

Part of the animosity in the 1828 campaign owed to the fact that in 1824, in what was the craziest election in American history, none of the four candidates — including Jackson and Adams — received a sufficient number of electoral votes to be declared the winner. In such a case, according to the U.S. Constitution, the final decision is made by the House of Representatives. And though Jackson had received a higher percentage of the popular vote, the congressmen made Adams the president. Jackson never forgave that slight.

Like Trump’s inexplicable persona as a “man of the people,” Jackson was not quite the commoner he portrayed himself as. In South Carolina, and then in Tennessee where he lived, he fancied himself a southern gentleman. He owned slaves and was a lawyer, land speculator, congressman and senator.

Nevertheless, the Washington establishment was aghast at the thought of Jackson’s inauguration in 1829, as much of the Washington elite is holding its collective breath at the thought of Trump’s inauguration on Jan. 20.

In 1829, the ruling class’s fear proved correct. Jackson offended custom by not wearing a hat to the ceremony. Worse, thousands of Jackson’s common-folk supporters showed up to cheer him on. Once he took the oath, this “rabble mob” stormed the podium and then the White House.

In presidential rankings, historians place Jackson high on the list. In office until 1837, however, he was as polarizing a figure as Trump is apt to be. Still, he used patronage to appoint hundreds of his loyal supporters to government positions, treated indigenous Americans abysmally, got rid of the Bank of the United States and maintained Adams’ protectionist trade policies against the wishes of the southern states.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the French diplomat who visited the U.S. in the early 1830s and later wrote about it, provided a more nuanced portrait of Jackson, arguing that as president he was not the despot European leaders believed.

At the same time, in words that ring true today, de Tocqueville added that Jackson was “supported by a power with which his predecessors were unacquainted; and he tramples on his personal enemies whenever they cross his path with a facility which no former president ever enjoyed; he takes upon himself the responsibility of measures which no one before him would have ventured to attempt: (and) he even treats the national representatives with disdain approaching to insult.” And he did this all without the commanding force of Twitter.

Nearly two centuries ago, Americans survived and even prospered during Jackson’s presidency. Here’s hoping that history is about to repeat itself.

Now & Then is a column in which historian Allan Levine puts the events of today in a historical context. His latest book is The Bootlegger’s Confession: A Sam Klein Mystery.