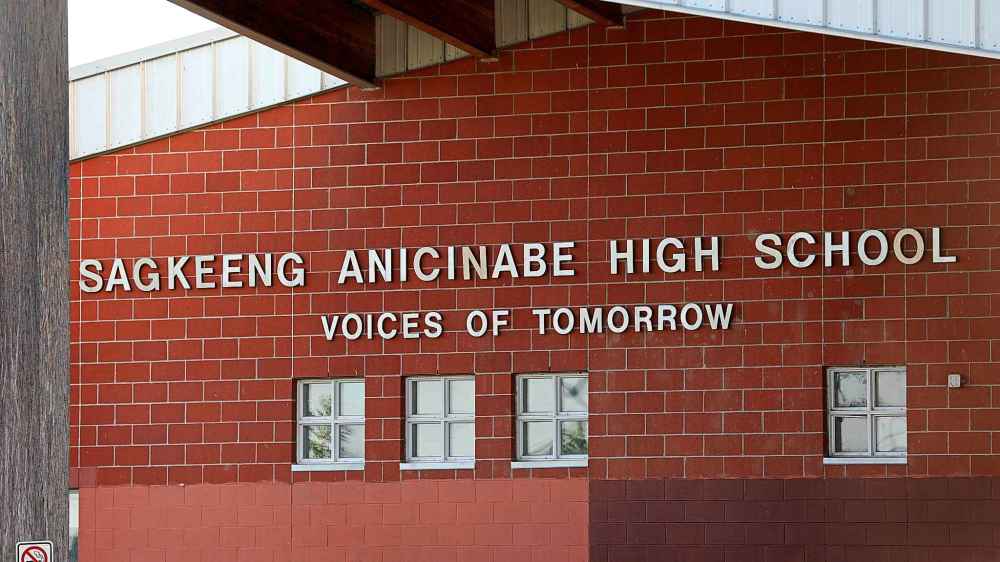

Voices of tomorrow Although their community has been marked by trauma and tragedy, Sagkeeng First Nation teens are cautiously optimistic about their future

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/06/2018 (2731 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

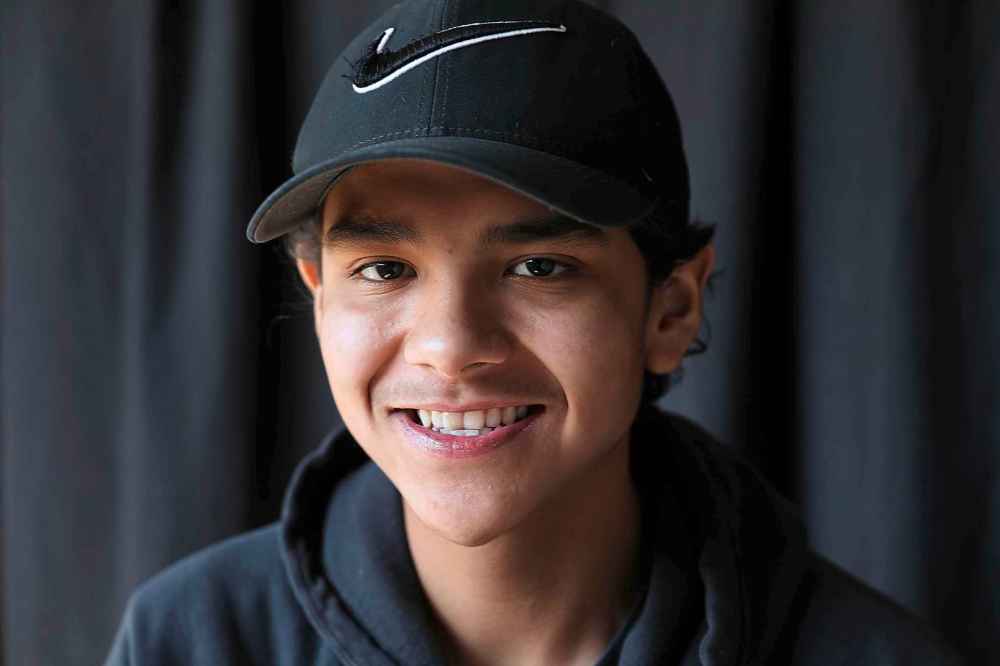

SAGKEENG FIRST NATION — Leading the way through the long grass, over a well-worn, narrow dirt path that cuts through a hilltop overlooking the Winnipeg River, Breanna Laforte heads down to the rocky shore.

As pelicans swim in the distance, a few boys call out hellos to her while they fish for pickerel on an outcropping that points into the water like a dimpled stone arrow.

Laforte greets them and looks out at the summer sunset, a wash of blazing orange reflecting on the river, making way for a deep blue twilight to blanket Sagkeeng First Nation.

When Laforte speaks, she does so with quiet confidence. At 17, she measures her words carefully, content to soak in the last light of a long day.

“Even when I was a little girl, I always wanted to be a kind of role model for people, just someone to look up to,” she says.

“I think if I lived somewhere else, it would be the same because of my mindset. My mind is set on being an advocate. I think it’s just because of the happiness that I get from helping.”

Somewhere else is hypothetical right now. Here is where Laforte was born and raised. Here is where the eldest child is trying to set an example for her five sisters, so no other girl will be afraid of going out for a walk and being abducted. Here is where her family and friends are, and here is where she’s studying Indigenous culture and Canada’s colonial history. The more she learns about the past, the more she’s excited for her own future and the possibilities it holds.

“I just always felt, as a seventh generation, that it’s me that has to change everything.”

She is one of 20 students at Sagkeeng Anicinabe High School who spoke to the Free Press, answering a single question: What are your hopes and dreams for the future?“I just always felt, as a seventh generation, that it’s me that has to change everything.” –Breanna Laforte

Their answers, shaped by their own experiences and passions, offer glimpses into who they are and who they want to become — not just for themselves, but for their community.

Their hopes are buoyant and contagious, their anxieties about the unknown tempering some of their idealism.

Some are motivated by what they’ve seen and heard. They say they want their lives to stand in contrast to others who’ve fallen off track, or to mirror those who’ve inspired them.

Even in conversations focusing on hope, there are clear undercurrents of fear and caution as some students talk about the effect drugs, violence, depression and suicide have had on their lives, and how they want to be different. They’ve felt unsafe and ashamed to be who they are. They are sick of feeling that way.

Some, such as Laforte, feel a personal responsibility to make changes that weighs heavily on their shoulders as they begin to plan ahead. And they look to those who came before them to make sense of what comes next.

•••

Behind Laforte, at the top of the hill, is the church cemetery where her friend Tina Fontaine is buried.

Nearly four years after the 15-year-old girl’s shocking death, Tina’s name is remembered internationally as a symbol of the many missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada — a touchstone of tragedy reaching far beyond this on-reserve community of about 2,000, located about 120 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg.

And she is not alone; others who’ve lived in Sagkeeng, which has experienced more than its share of violence, are counted in that troubling national MMIW number.

Earlier this week, the second of two teenage girls appeared in court to await her sentence for beating to death their high school classmate, 19-year-old Serena McKay, in April 2017. The beating was filmed on a cellphone camera and shared on social media for the world to see, again drawing national attention to violence and substance abuse in Sagkeeng.

Less than a year after Serena’s murder, a long-awaited verdict attracted international headlines and local outrage as the man accused of killing Tina was declared not guilty by a jury that spent nearly a month over the winter hearing details of the criminal investigation.

This summer will mark four years since the petite teen left her home in Sagkeeng to visit her mother in Winnipeg, only to wind up on the streets, looking for a safe place to go. Her tiny body was pulled from the Red River wrapped in a duvet cover on Aug. 17, 2014 — a discovery that sent shock waves across the country, leading to a national inquiry into murdered and missing Indigenous women and girls and amplifying repeated calls for change to the systems that are supposed to protect society’s most vulnerable.

“We, as a nation, need to do better for our young people,” Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak grand chief Sheila North said minutes after Tina’s accused killer was acquitted in February.

Through the marches for justice, love and peace that followed Serena’s slaying and the high-profile acquittal of Tina’s accused killer, rallying cries for the voiceless were re-ignited.

“Quite often, the voices of young people are not listened to. And grandmothers are pretty fierce in terms of love for their children,” Indigenous researcher and professor Dr. Marlyn Bennett said in a previous interview, while reflecting on her 2016 report for Manitoba’s Children’s Advocate. The report, a direct result of Tina’s death, produced recommendations to help other Indigenous girls in the province.

But in this First Nation community that to outsiders is known because of the tragedies, so many people are determined to move forward, and they’re turning to the next generation to find a way. Sagkeeng is decidedly youthful, with about 30 per cent of its population under the age of 15. And many young men and women — some older than Tina and Serena ever got to be — are finding their voices.

It’s up to us to listen.

•••

“Hey, Granny?” Colton Kent begins. The 19 year old is seated on a folding chair on the porch while Margaret Bruyere, the woman who raised him, chats with a reporter in her yard.

Someone has just dropped off a can of baking powder so Bruyere can bake her promised bannock.

“Did you have a TV growing up?” Kent asks.

“Not really,” she answers.

“Did you ever watch those John Wayne movies?”

“Yeah,” Bruyere says, smiling patiently.

“Did you ever notice how all the natives were always played by white actors?”

“Yeah!” Bruyere says with a laugh. Back then, she says, it wasn’t something she spent much time thinking about.

But her grandson has. Kent’s been thinking a lot about how Indigenous people are portrayed in media, and how he can make his mark in writing and film and start to see the beauty in his community.

“I always got my answers and my morals from the television, watching films and all that. That’s probably why I’m so into it,” he says.

He dreams of seeing his name in the credits of a film — one he hopes features a Black Panther-like Indigenous superhero. It’s time, he says, to see more protagonists grappling with questions of cultural identity.

“I never heard anyone talk about feeling disconnected from your people. I feel like that’s a big, relevant topic that no one’s talking about. I know there must be kids that feel the same way or felt the same way.”

In late June, he became the first person in his family to graduate from high school, one of 23 in the community this year. He wants to earn enough money this summer to buy some video equipment to try to capture the Sagkeeng he sees: a place of endurance.

“With my people, growing up, we wouldn’t see the best images, you know? Like, there’s a lot of drugs and alcohol and addictions,” he says. “There’s a lot of violence, there’s a lot of hurt. And that’s all you really see down here. Sometimes it takes its toll.”

He didn’t know Serena McKay, a fellow student at Sagkeeng Anicinabe High School, but her April 2017 slaying hit him hard.

“I still felt it,” he says. “And that’s when I realized, you know, we’re spilling our own blood, and it shouldn’t be like that. You know, we shouldn’t be against each other.”

To other young people, Kent says, “You’re going to see a lot. You’re going to see our people at our worst. But you’re also going to see our people at our best, and it’s up to us, you know, to show that.”

•••

Red yarn loops through hula hoops as Grade 12 girls make dream catchers to decorate the Sagkeeng Arena Complex for their graduation ceremony.

Swaths of coloured duct tape — red, white, yellow and black — transform the hoops into medicine wheels. They are spiritual symbols of universality, the significance of which isn’t lost on 18-year-old Mandy Hope.

She sets down her yarn to tell the story of how she got her spirit name, Thunderbird Woman. In a moment so naturally poetic she felt compelled to write about it in what would become her first published poem, the skies opened on her way to the summer Sundance ceremony.

“Clouds were coming real fast,” she remembers.

Rain hammered down. The sky was dark and overcast. But just after the medicine man named her, they cleared. The sun shone through.

“It made me feel powerful,” she says.

“As a person, I’m still trying to figure out who I am,” Hope says. Writing about it, she adds, “helps me emotionally.”

The experience inspired her to learn more about the “untold stories” surrounding residential schools, the ‘60s Scoop and the Indian Act. Through her writing, she wants to “bring what happened in the past” into the present.

Hope explains how her Indigenous issues education is shaping her view of the future. The curriculum at Sagkeeng Anicinabe High School includes dedicated courses on residential schools and Indigenous history, classes that didn’t exist a generation ago.

“Right now, the picture that we have, there’s more kids getting into their culture,” says 20-year-old Pauline Guimond, valedictorian for the class of 2018.

“We’ve never had that before.”

•••

“I really envy them, because we didn’t learn that when we went to high school… it was all hidden. I learned it in university,” says Darlene Starr Courchene, a residential school survivor from Sagkeeng who obtained her social work degree in the spring.

“The young people nowadays are free to tell. They have a voice — they’re getting a voice. Whereas we didn’t, it was all hush-hush.”

She says she finds it easier to talk to her granddaughter, 17-year-old Dyani Langridge, than it often was to broach tough topics with her own kids.

“I’m able to talk to her about abuse. Any type of abuse. Emotional, physical and what to watch out for,” Courchene says.

In the generation gap between grandmother and granddaughter, there has been room for both to grow.

Now, when Langridge thinks about the future, her mind turns automatically to the bigger picture. Like many of her peers, she expresses trepidation. She mentions Tina Fontaine’s name as she considers what’s ahead for her. No one in her immediate family has gone missing, she says, but the thought stays with her.

“Now that I’m older, I constantly think if it’s going to be me, or just anybody else,” she says.

“Because of all this, I can’t really go out anywhere on my reserve,” she adds, describing the mixture of sadness and anger she feels, “because I don’t know why people would do this to each other.”

But then a broad smile spreads across her face as she speaks about her passion for drawing and the many career paths she could take. In this moment, though, her own path seems an afterthought to her vision for her world.

“Everything will be better… there’ll be no arguments or no missing women or murdered people or kidnappings or anything,” she says. “Or no issues amongst natives or just other nationalities. That’s… the main reason why everything bad is happening, because everybody goes against each other.”“There’s always hope. If you don’t have hope, you don’t really have anything.”–Darlene Starr Courchene

Understanding the past and being aware of current issues is crucial to moving forward, Courchene says later.

“When I talk to Dyani about issues that we’re afraid for her, I guess that’s where it stems from. I sometimes wonder if we’re overly cautious… it’s based on things that we’ve experienced.”

But, she adds, “There’s always hope. If you don’t have hope, you don’t really have anything.”

And her granddaughter supplies her with that hope.

“I see her with her friends,” Courchene says. “They watch out for each other.”

•••

The cedar tree in the front yard is older than Pat Cook’s only child. The seedling was her Mother’s Day gift to her own mom 25 years ago, its wood a sacred symbol of protection long relied upon in traditional medicines.

Now, its branches surpass the rooftop of Cook’s home, curving upward to the sky.

As many of Sagkeeng’s youths contemplate leaving the community to pursue their own goals and expand their horizons, others worry about abandoning their home, and think about staying put to help it grow.

The Cooks are balancing a bit of both.

When Pat returned to Sagkeeng last spring with her now-19-year-old son Vaughn, it was a healing homecoming. Time for her to recover from breast cancer and reconnect with her roots after a 30-year career as a social worker.

For Vaughn, who grew up in Saskatchewan, Winnipeg and Brandon as the family moved around, spending his senior year of high school in Sagkeeng was akin to “culture shock,” he says.

A little while after they moved back, “he said he wanted to do what I do,” Pat says.

Proud he wanted to follow in her footsteps, Pat told him social work was a challenge — one Vaughn was up for.

“I know it’s a tough job. But it’s something I want to do, not only for me, but for my people,” he says.

“I like knowing somebody’s story. I like hearing what they have to say. I like hearing how they feel. I like knowing that if I can help, I totally would. If there’s any way I can help, I will.”

As is the case with so many of the young people who share ever-evolving dreams, Vaughn’s career path is mostly set, but he’s kept an open mind, knowing how quickly things can change.“I think we need to shed some light on the good things that are happening… (the youth) are gifted and we need to let that shine.”–Pat Cook

And things have; he’s jumping at the chance to play junior football in Victoria on the Westshore Rebels offensive line. He’ll head to training camp in a few weeks.

“It’s been a rough year for both of us, but Vaughn’s going to spread his wings,” Pat says, beaming at her son. “There’s been some tragic things that have happened in the community.

“I think we need to shed some light on the good things that are happening… (the youth) are gifted and we need to let that shine.”

•••

We asked 20 high school students from Sagkeeng to tell us about their hopes and dreams for the future. This is what they said.

Colton Kent

Age: 19 | Career goal: Screenwriter

“One dream for the future is seeing my name in the credits of a film.”

Colton would like be a writer and create Indigenous characters for other people to look up to.

“I am thinking of something. I do have an idea, and it is something that I want to do with cultural identity and sense of a purpose, I guess. That’s what I wanted to write first. Just write what you know, I guess, and that’s what I know.”

Pauline Guimond

Age: 20 | Career goal: Teacher, Indigenous leader

“I want to teach our youth here, I think that’s very important. And I want to be a role model. I want to be a leader.

“I just want to strive, you know, I want to keep pushing myself I’m not going to let anything drag me down.”

Berry O’Laney

Age: 15 | Career goal: Pilot

“I really want to become a pilot. I want to be able to help kids rise up.”

Dyani Langridge

Age: 17 | Career goal: Animator

“The main reason why everything bad is happening because everybody goes against each other. (In the future) everything will be better, like they’ll be no arguments or no missing women or murdered people or kidnappings or anything.”

Breanna Laforte

Age: 17 | Career goal: Indigenous advocate

“I want to be a politician to fight for Indigenous people and our rights. I don’t want girls like me to be scared to walk around anywhere…to be abducted.

“I just want to show my sisters a good example and stuff like that, and raise them to be helpful and caring to other people.”

Jeffery Sinclair

Age: 15 | Career goal: Artist

“I want to be an artist. It helps me because it makes me just let go and start thinking to what I’m going to paint.”

Clorissa Letander

Age: 16

“I hope that things look brighter, more kind.”

Clorissa is a published poet who mentors younger girls and loves basketball. Her philosophy is to “live like every day is pretty much your last, enjoy life as much as you can, find a solution to a stressful situation as much as possible.”

Mya Bird

Age: 15 | Career goal: Singer

“I would actually like to be a well-known singer.”

“My favourite song, I think it has to be, it’s really an old song, it’s from the band Journey: Don’t Stop Believing… I can hit the high note, too, to be honest.”

Sage Seymour

Age: 16 | Career goal: Hockey player, firefighter, carpenter

“I just got family that do everything around here… my parents always tell me get your school done and you’ll find a good job.

“I just want to take up a profession like my parents.”

Vaughn Cook

Age: 19 | Career goal: Social worker, football player

“My dream is to become a social worker and to hear people’s stories.

“I like knowing somebody’s story. I like hearing what they have to say, I like hearing how they feel. I like knowing that if I can help, I totally would. If there’s any way I can help, I will.”

Kelly Smith

Age: 18

“I just want to see more people healthy and happy.

“I just want to get a message out there as much as possible that we too value our culture and that we too now are suffering with that loss of identity.

“And I just want to remind all the youth that we should be proud of who we are and what we came from.”

Amy Swampy

Age: 18 | Career goal: Working in agriculture

“I think about our home planet and how we can start caring for it better.

“We gotta take care of it because we belong to this planet. It does not belong to us. So we’ve got to be good to it, so it will be good to us.”

Akiva Starr

Age: 15 | Career goal: Become a surgeon, adopt kids

“I want to give a kid a good life, like a better life than what I had to go through.

“If you stay in the past, you ain’t going to get anywhere in life.”

Peijkomeengwan Courchene

Age: 16 | Career goal: Politician/lawyer

“I want my people to be treated as equal. I don’t want to go to into a store and just (be seen) as a thief right away. That was hurting me even as a little kid.

“I used that for motivation. I didn’t get mad, I didn’t get sad. I was just like ‘whoa, whoa, I’ll show them who can be wealthy.’”

Payton Swampy

Age: 15 | Career goal: Lacrosse player, construction worker

“It runs in the family, so I gotta play lacrosse (laughs).”

Hailie Bruyere

Age: 17 | Career goal: Military

“I actually do think about the future a lot, honestly, like so much, all the time (laughs).

“Going through basic training (during a youth military program) made me think about the future more because, well, it opened a lot of doors, actually.

“What my instructors did for me, I would like to do that for other recruits that are joining the military… if they want to be in the military, I want to teach them what to do, and you know, respect, discipline, all that stuff that I (learned) I want to teach them.”

Mackenzie Guimond

Age: 16 | Career goal: Counsellor

“I want to be a counsellor. Because I have been through so much… and I just want to fulfil what I’ve been through, but in a positive way.”

Sebastian Peebles

Age: 15 | Career goal: Basketball player

“My dream is to be an NBA all-star.”

Chloe Courchene

Age: 18 | Career goal: Working in criminology

“What gives me hope? I really don’t know, actually (pauses). I would say my family gives me hope, because most of us are great, so far.

“I still have a long way to go, but I’m really excited for my future.”

Mandy Hope

Age: 18 | Career goal: Writer

“A lot of youth my age don’t really get their voices out, and I think that by becoming a writer I can help them get their voices out.”

•••

Katie May is a multimedia producer for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, June 29, 2018 6:23 AM CDT: Corrects that Breanna Laforte is 17 and has five sisters