Wish lists from the front line: Medical examiner

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/12/2008 (6292 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

MANITOBA’S chief medical examiner says the most profound damage done to children doesn’t result from a troubled child-welfare system.

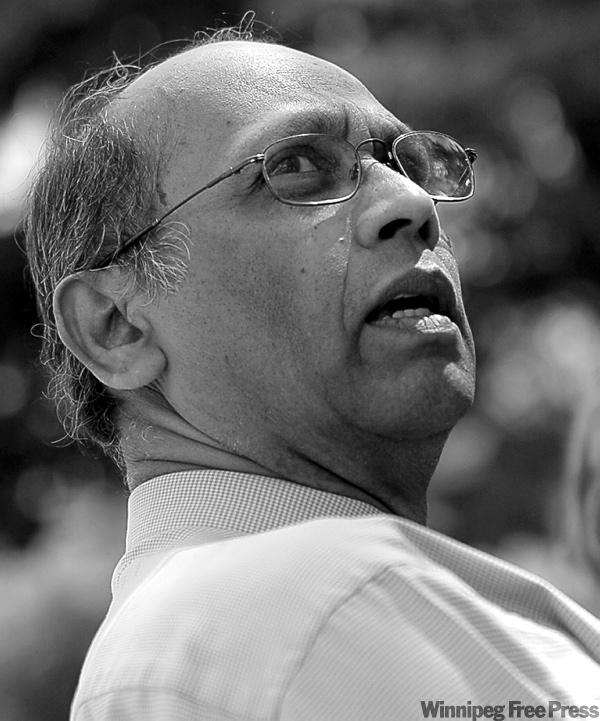

For Dr. Thambirajah Balachandra, the root of the problem is poor parenting, exacerbated by atrocious living conditions on the province’s remote reserves.

"If the parents are capable, if they don’t drink or neglect their children, so much of this can be prevented."

He says addressing the root causes of family violence would save children.

"What would I do if I had no money? If I was living in places that are like concentration camps? There’s no hope. They’ve lost their traditional way of life. They drink, they do drugs. I, too, would do the same thing.

Balachandra says substantial support for parents and communities would diminish the need for a bulky child-welfare system.

Balachandra’s office conducts the inquests of children who die in care or within a year of having some involvement with the child welfare system.

Until recently, his office also conducted mandatory Section 10 reviews — death reports — on those children. But the Office of the Children’s Advocate is now responsible for those. When that was transferred, there was a backlog of some 100 cases the chief medical examiner hadn’t had the resources to complete.

Many of those reports remain unfinished.

Until some way can be found to address and resolve the inequities, Balachandra says, more children will require care and more children will die. "This is a systemic, long-term problem.

"People should care for their children. They shouldn’t take alcohol, they shouldn’t take drugs," he says bluntly.

"Maybe they shouldn’t have so many kids. It’s overwhelming."

lindor.reynolds@freepress.mb.ca