Folklorama: ‘This is us’

In a time marked by divisive politics around the world, the inclusive message of Winnipeg's long-running multicultural festival has never been more resonant

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/08/2018 (2758 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It was a sunny Tuesday afternoon, and Folklorama’s pre-festival media blitz steamed ahead as normal. The Caboto Centre’s atrium buzzed with people nibbling festive doughnuts, squeezed by stands of TV cameras.

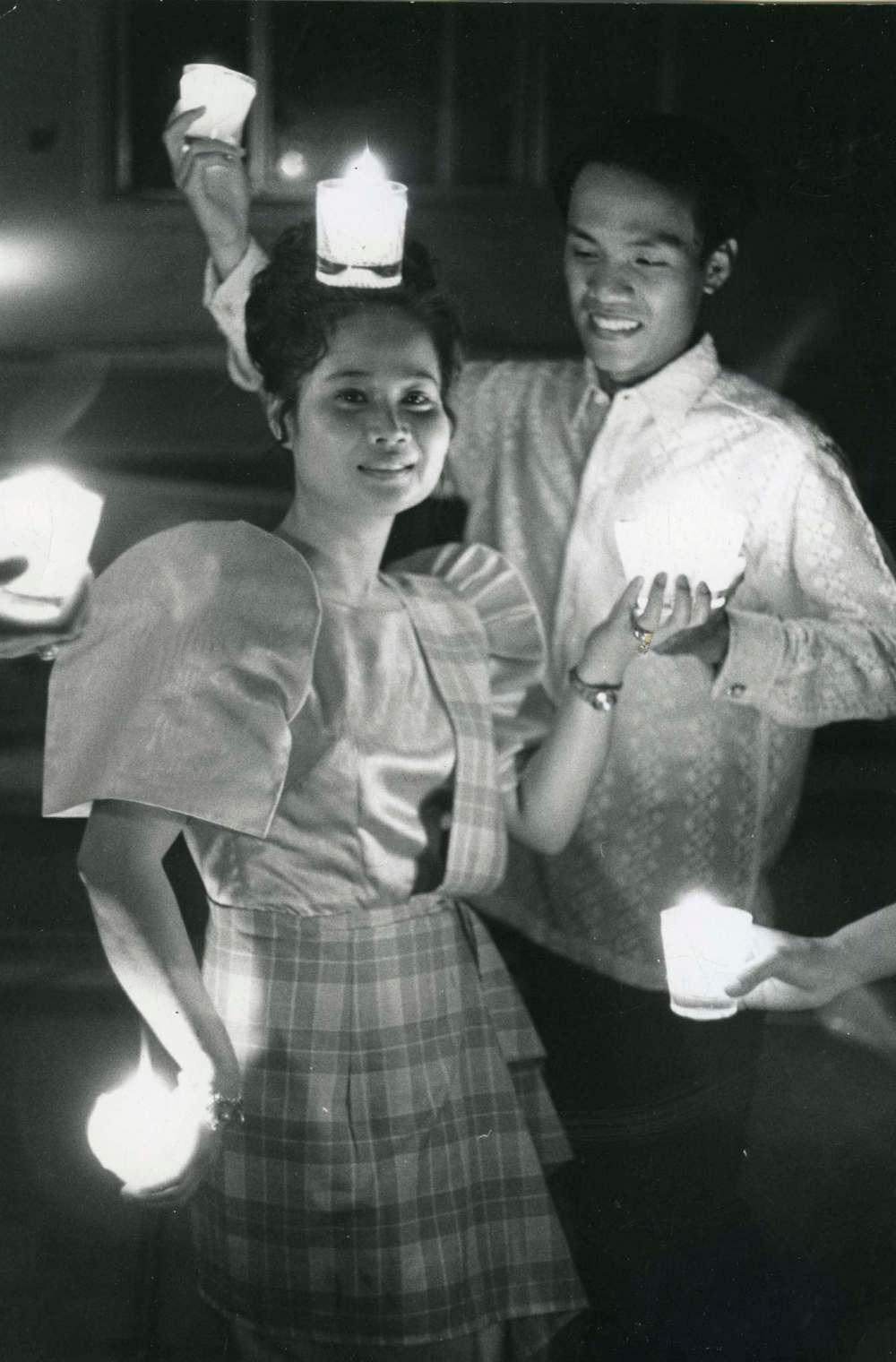

The festival’s pavilion ambassadors, resplendent in their culture’s attire, breezed through the room in blooms of colour. The Asham Stompers dance squad, stars of a brand-new Métis Pavilion, whirled through a Red River Jig.

When it came time for speeches, Mayor Brian Bowman rose to his feet. He shuffled his papers at the podium, joked that he hoped the media didn’t see. Then, he said something that, in this world, was a little unexpected.

With forces around the world trying to divide people, he mused, we need Folklorama more than ever before.

There was a heartbeat of surprised quiet, then a burst of vigorous applause. Bowman went on.

“The forces who try to divide people, usually try to do so by spreading misinformation and fear,” he said, and pointed to Folklorama’s 43 pavilions as an antidote to that process, a festival to reaffirm what unites cultures.

“There are some pretty common themes,” he continued. “A focus on family and community, making a living, happiness, and pride in one’s culture. There are so many more things that make us similar, than divide us.”

It was not a radical sentiment. Yet here, in the heart of Folklorama, even that reference to divisive politics was unexpected. Since its inception, the festival has been staunchly non-political; its supporters usually follow suit.

This time, perhaps, someone needed to say it. Bowman’s comments arrived at a pivotal moment: all across Canada and the United States and Europe, a battle is churning. It is about refugees and about immigration.

It is also, from its most extreme edges, about the future of multiculturalism, and ethnic diversity itself.

In the United States, a man gets elected president while pledging to clamp down on immigration and deport refugees already legally arrived in the country. In Canada, far-right agitators Tweet abuse to Muslim reporters.

On social media, videos of racist abuse and harassment spread like wildfire. The incidents flow in from every corner of North America: at a restaurant in Lethbridge. A ferry dock in Toronto. A supermarket in London, Ont.

Words give way to violence. In 2017, a man in Quebec murders six people at a mosque. In Kansas, a man opens fire on two Indian men eating dinner at a restaurant, killing one; witnesses hear him yelling “get out of my country.”

Those incidents are just a handful of many. And it has always been there, this hatred; yet lately, it seems more open, more concerted, more emboldened by the victories of politicians touting hardline anti-immigration policies.

In the wake of last month’s mass shooting in Toronto’s Danforth neighbourhood, Imam Tawhidi Tweeted that “multiculturalism,” “diversity” and “inclusion” are the “three words that have destroyed Western civilization.”

Now, those troubles have hit Folklorama, too. Just one week before the festival’s kickoff, a Canadian Nationalist Party speaker held a meeting at the same Provencher Boulevard venue which usually hosts the Belgian Pavilion.

Only three people showed up, and the meeting was disrupted by local anti-racist activists. But outside, a Belgian Club board member complained to activists about how only “visible minorities” can get jobs with the government.

The Belgian Club soon announced the board member had been asked to resign. Days later, the pavilion itself announced it was voluntarily withdrawing from Folklorama, saying it was time to “pause, reflect and step back” for this year.

Each of these threads weaves into a larger message, pushed by agitators and extremists the world over. The message is simple, its ramifications brutal and stark: suspect your neighbour. Close the doors. Build the wall.

Through this storm, Folklorama sails along, now in its 49th year and showing no signs of slowing. On the surface, nothing about it has changed: the dances, the songs, the steam tables laden with hearty stews remain the same.

But still, this moment in history begs to bring the matter to closer attention. What does it mean to hold a multicultural festival, in an era when the value of multiculturalism itself seems ever more under assault?

● ● ●

To understand the spirit of it all, maybe one has to go back to the very beginning.

If you’d told Sid Ritter in 1970 that he’d still be part of Folklorama today, he wouldn’t have believed you. The event was organized for Manitoba’s centennial; it was supposed to last just a week, not well into the next millennium.

That first festival, it was a labour of love. The city chipped in $15,000 to start it up, and organizers worked mostly after-hours. It looked a little different than today’s Folklorama: there was a beauty contest, a casino-themed venue.

Yet even then, the familiar shape of the festival was clearly visible. Twenty-two pavilions set up in humble community spaces across the city; a $1 “passport” was good for free bus rides and discounted admission.

Days before kickoff, the Free Press ran a feature brightly announcing the festivities.

“If you do nothing else this summer, you must visit Rome or Athens or perhaps something a little more unusual like Seoul, Korea,” it read. “There can be no excuses such as ‘no money, no time’ or ‘I don’t speak the language.’”

Winnipeggers, as it turned out, needed little convincing. People flocked to the pavilions “by the busload,” the Free Press reported; line-ups stretched down the block. By the time it was over, attendance had surged past 70,000.

At the first Israel Pavilion, Ritter — who later served as Folklorama’s president in 1981 — was amazed by the enthusiasm. He stood outside and listened as attendees chatted about where they’d been, what they’d seen.

And they were also impressed by how the event seemed to smooth lurking frictions. The Second World War was relatively fresh in living memory; some Winnipeggers initially balked at the German Pavilion. But it too was a hit.

What organizers realized, in that moment, is just how hungry Winnipeggers were for a space where asking questions wasn’t only permissible, but encouraged. Folklorama provided that space, in a way little else did.

“Generally speaking, people are curious,” Ritter says. “They want to know. And if you encourage them to find out, and to ask, and to go and to see and to look, they all of a sudden get a much more integrated community.”

The timing was perfect. In 1970, Canada was in the midst of a major transformation. The nation had recently overhauled its immigration system, cutting restrictions against non-Europeans and opening itself to refugees.

Before 1970, around 1 in 10 immigrants were non-white; over the next decade, that figure rose to nearly half.

This new ethnic diversity took on a sort of momentum. Multicultural festivals sprouted across Canada; in 1971, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau rose in the House of Commons, and announced a new multicultural policy for the young nation.

Folklorama tapped into that energy. To be clear, this was no utopian time: xenophobia and racism were alive and well in the 1970s. But there was, Ritter says, a sense of excitement in exploring the country’s growing diversity.

“As far as this community is concerned, I think we played a big role in promoting that,” he says. “People were no longer afraid to invite people to come to their community. They were so proud to show what they were all about.”

The years turned. Some of the other multicultural festivals founded in the same era eventually fell away, but Winnipeg’s only grew stronger; in recent years, attendance consistently hovered somewhere above 400,000.

One survey found that 43 per cent of Manitobans plan to attend in 2018; nearly a third say they went last year.

“We always encouraged to show who you are, tell who you are, don’t hide who you are,” Ritter says. “It seemed to be working. And it’s still working today.”

Folklorama is, today, one of the most familiar rituals of a Winnipeg summer. Several generations of families have now grown up with its rhythms, helped out at pavilions, and brought their own kids to soak in its infinite colours.

Meanwhile, the festival hasn’t changed so much from the origin spirit of its era. But has it changed us?

● ● ●

Usually, Florence Okwudili is an avid news-watcher, but there have been days, as of late, when even she has to turn away. The headlines have been so bad, she says, sipping coffee at a Tim Hortons on a windy afternoon.

Sometimes, when she hears news about conflict and tensions, her thoughts flash back to Folklorama.

“I listen to the news a lot,” she says. “You hear about all these (issues around) diversity of religion, tribes, languages… they don’t know that all of those diversities can be managed together, by things like this.”

And Folklorama has been an essential part of Okwudili’s Canadian experience. She discovered the festival not long after moving to Canada from Nigeria in 2000; her first thought, when she encountered it, was simply “wow.”

Now, she’s in her 13th year as co-ordinator of Folklorama’s Africa Pavilion. Her children grew up dancing there. This year, her grandchildren will be dancing for the first time. She often reflects on what Folklorama taught them.

After all, she muses, her kids didn’t grow up the way she did, where “everywhere I look is Nigerian.” Their world is one of diverse friendships, and creating fusions: Folklorama, she thinks, taught them how to build those bridges.

“How do they really mix up these cultures without feeling inferior or superior, but learning that something binds us together?” she says. “Through their culture. Cultures might be different, but the more different is the more exciting.”

In her view, Folklorama has become a home, of sorts, to newcomers and their descendants. Each year, Okwudili brings newcomers to the Africa Pavilion; each year, she watches their eyes grow wide with delight and surprise.

“The unseen benefits, the impact of Folklorama, for refugees and immigrants… it gives you that feeling of, this is your home. You are not here alone,” Okwudili says. “That’s something politics does not provide for people.”

Does this sense of being anchored spread through Winnipeg as a whole? One of Folklorama’s central planks is that every pavilion is equal: everyone who comes can see themselves in it, celebrated as both different and same.

In truth, relatively little research has been done into the broader effect of multicultural festivals. Academics have explored how they build self-esteem amongst participants, and seem to build bonds across a community itself.

From her vantage, Okwudili is convinced that Folklorama can create wider change. She sees it in the youth.

“They learn to admire other people, it doesn’t matter where they come from,” she says. “And they are open to learning more and more. So I do see the Folkorama family being that block to build a stronger community.”

Now, that message may be especially critical, even if Folklorama does not directly address rising tensions.

Folklorama was never radical. Its political disengagement is, depending on your position, comforting or frustrating, hopeful or hopelessly naive. Folklorama’s multiculturalism is always sunny, unbothered by the tensions of the day.

That non-political commitment serves noble aims: for one thing, it ensures that geopolitical conflicts don’t cause rifts between pavilions, or rend the festival itself. But it also stops it from taking a stance on key human issues.

Still, maybe there is another way of looking at the festival’s political impact — one that is not said, but felt.

Folklorama changes very slowly. But it does change, largely as a result of new cultural communities entering the fold. New pavilions are embraced by waves of enthusiasm; they are often led by youth, and bustle with energy.

Consider the South Sudanese pavilion, one of Folklorama’s newest. This year, it is co-ordinated by two 23-year-old women. Elsa Kaka is a law student, who volunteers with a justice non-profit; Akech Mayoum is in nursing school.

These young women are the future of Canada, and the future of Folklorama too: “I like organizing things,” Kaka says brightly. Like Okwudili’s kids, they grew up around the festival, and imagine their own kids doing the same.

When Kaka looks at the divisive rhetoric screaming in the headlines today, she sees a lot of things: a lack of education. Loud voices. Hateful ideologies that have always bubbled close to the surface, bursting through.

She also sees a chance to counteract those messages, to strengthen the places where fractures start.

“If we look at it as an opportunity to really learn about the importance of diversity, and multiculturalism, and really loving your neighbour, if we look at it from that perspective, then we’re in a great time,” Kaka says.

And maybe that is the heart of Folklorama, the role it can play. If the festival is officially non-political, it is also indivisible from its vision of community: the world it creates is renewed by diversity, never threatened by it.

These days, maybe, loving that vision can be a political act too. And standing up to be counted amongst the myriad cultures, to be seen and be heard and welcome questions, is part of reaffirming that core conviction.

Maybe it can serve as an antidote to divisive forces. Or maybe, it just gives a blueprint for how to push back.

“Even now that politics is getting more and more terrible, every culture sees Folklorama as an opportunity to display that aspect of their country that is welcoming, that is friendly, that is not all you are hearing,” Okwudili says.

“This is us. Folklorama provides that opportunity to show that. And that’s why it keeps growing.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, August 6, 2018 1:28 PM CDT: adds slideshow