The water also rises

Project brings dredging back to 'devastated' Netley-Libau Marsh in effort to correct flow, re-establish plant life

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/05/2021 (1720 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The reflections of migratory birds whiz by Charlie McPherson’s binoculars as he faces southwest down the shoreline. The sun is just now breaching the distant, still-frozen expanses of Lake Winnipeg.

The early morning light casts an orange hue on the waist-high grass. Duchess — McPherson’s springer spaniel — sticks close by his side, nibbling burrs out of her long, wavy fur.

McPherson lowers the binoculars and jots down an entry to today’s list of findings: one sharptailed grouse, one western meadowlark, seven green-winged teals, 26 rusty blackbirds, 28 herring gulls.

“It’s the place to bird,” he said. “I don’t go anywhere until May.”

McPherson founded Dunnottar Bird Watch more than a decade ago. Since then, nearly every day at the crack of dawn, he drives down to where Warner Road meets the beach ridge.

Many migratory birds use the Red River as a corridor when travelling north for the summer.

Once the birds reach Netley-Libau Marsh — believed to be the largest inland freshwater marsh on the continent — they bank left or right. The province dubbed this region one of Manitoba’s 36 important bird areas.

But there are far fewer birds to count these days because of habitat disruption, McPherson said.

“Twenty-five-thousand mallards and wood ducks used to breed and molt there. Those numbers have dropped to less than 1,000.”

The Red River Basin Commission — a multi-jurisdictional non-profit — and a laundry list of enthusiastic stakeholders plan to break ground with the Netley-Libau Marsh restoration pilot project in August.

“We wanted to make sure that we started moving forward that we recognized this is the traditional lands of the First Nations, especially Peguis First Nation,” said Steve Strang, head of the Red River Basin Commission’s Manitoba chapter.

Chief Derrick Henderson of Sagkeeng and Chief Deborah Smith of Brokenhead have backed the project from the start; seven First Nations are helping to finance the project, Strang said.

“I am so passionate about this project because I have three children. I want those children to know that I made every possible attempt to correct something I think is so wrong,” he said. “We have to understand that there is a huge value to the environment, and we need to start paying it back.”

The pilot project is two-fold: dredge parts of the wetland to correct water flow and use the extracted material to create elevated “reefs” where plants can flourish once again.

“The Prairies have been hit the worst within wetland loss,” Strang said. “It is said that we have lost 90 per cent of the wetlands in some areas.”

Dredging is not a new concept in the Netley-Libau Marsh.

As early as 1883, workers extracted Red River sediment from its main channel — known as the Netley Cut — to make way for barges and pleasure craft. The federal government stopped the dredging in 1999, and today, siltation packs much of the channel.

Up to 50 per cent of the Red River diverts back into the marsh, depending on water levels and wind direction, Strang said. It is filling in places it never has before — or at least so severely and regularly.

“The marsh has just been devastated,” McPherson said. “It’s just wide-open. A perpetually flooded marsh is a dying marsh.”

Areas once considered “hemi-marsh,” vast expanses of wetland with a 1:1 ratio of submerged and above-water plant life, have transformed into shallow lakes. In 1960, there were 50 individual water bodies within the marsh, according to the Lake Winnipeg Implementation Committee report.

Today, a fraction of bloated lakes remain.

The pilot project — a marriage between biology and engineering — will focus on restoring the southeast corner of Netley Lake: a 60-square-kilometre region that reaches depths of two metres.

“You will never get plants growing in those parts of Netley Lake,” said Gordon Goldsborough, biologist, project adviser and local historian.

Goldsborough said this area poses a particular challenge, which makes it a good test subject.

“The prevailing wind direction here in Manitoba is from the northwest,” he said. “The place where the waves crash is at the southeast side. If there’s bound to be any wind-caused erosion, this is where it will be.”

The University of Manitoba scholar has advised other wetland projects in the past, including the Delta Marsh restoration that had thousands of invasive, trouble-making carp removed from the waters.

The plan is to dredge the Netley Cut and deposit that soil on sections of the marsh’s floor to create elevated regions — including embankments. By lifting the marsh floor, ideally, the sun’s rays will reach the seed bank nestled within the local wetland soil, causing the plants to germinate by the end of summer or early next year.

“We’re hoping that nature will help us along the way,” he said.

Scientists picked this area because it presents the most significant challenge.

The deep pools of water and subsequent waves have staved off much of the area’s plant life, such as the towering cattails. Big waves have also carried away hundreds of trees lining the marsh.

These treed areas provide much-needed shelter and shade for flora and fauna.

“The less vegetation you have, the more wave action you’ll get. The more wave action you get, the more erosion you get in the places where plants can occur,” Goldsborough said.

He calls this cycle a “positive feedback loop,” although, in this case, the net effect is damaging.

To dredge the soil, the basin commission contracted Quebec-based company Normrock Industries for its insect-like Amphibex machines. (Originally designed for dredging, Manitobans know about these apparatuses for breaking up Red River ice in the spring.)

“If it works — and we’re hopeful that it will — then the next step would be to try and do it on a larger scale,” Goldsborough said. “We’re going to learn so much along the way.”

Strang, former mayor of the Rural Municipality of St. Clements, said the project is forward-looking and “multi-beneficial,” pointing to like-minded projects in coastal Louisiana.

“They’re doing it for the purpose of flood mitigation,” he said. “All this vegetation starts to store carbon again.”

The Red River contributes 17 per cent of the water into Lake Winnipeg, yet it’s responsible for ushering in 70 per cent of the total phosphorus load. Presently, much of the river’s nutrients are flowing into a wetland unequipped to bear the burden.

“Those nutrients are now flowing into a marsh system that doesn’t have vegetation,” Strang said.

He added scientists working on this project and others studying similar initiatives said Netley-Libau marsh could absorb up to six or seven per cent of the nutrients entering its system, if it functioned at its 1990s rate.

Six or seven per cent is equal to or more than the amount of nutrients entering the lake because of human activity in Winnipeg.

“The City of Winnipeg is on board with this pilot project because they see it, potentially, as a way to offset their impact on the water quality of the Red River at a relatively low cost and in a way that is sustainable,” Goldsborough said.

Goldsborough admits the marsh isn’t a panacea for Winnipeg’s wastewater woes, and city officials know this, but the region could act as an effective buffer to trap some algae-causing nutrients before they reach the lake.

A healthy marsh could also increase the south basin’s fish population by four to five per cent.

Many people who’ve lived or spent time near Lake Winnipeg recount stories of meandering shorelines, rising and falling water levels, crunchy zebra mussels, the ghostly howls of shifting ice — how the water is or used to be.

The region’s natural systems have mystified Roxane Anderson for most of her life.

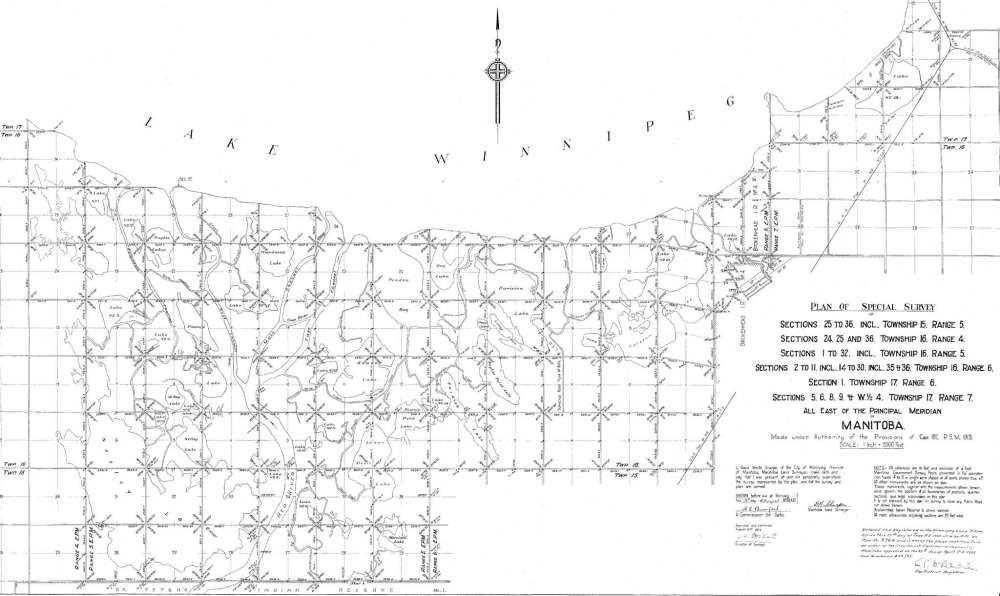

Anderson lives “12 miles as the Franklin’s gull flies” upriver from the marsh. A dense stand of poplar and oak trees shelter her home that’s nestled within a recently built ring dike on river lot 95. Early maps of Netley-Libau Marsh dating to 1934 line her hallway.

Just up from the road from her house, a “prairie pothole” — a tiny wetland dimpling the landscape. Ducks Unlimited has stewarded the cattail-rimmed pond and is also supporting the Netley-Libau restoration.

Anderson is familiar with McPherson, his birds and the restoration project. The last time she boated through the marsh, its degradation struck her.

“It was just water — everywhere there was water,” she said. “And the trees have declined. The marsh used to have all these little inlets.”

Anderson is in the final stages of writing her second memoir, Moving the Flood. Anderson began writing the book with her late husband after the freak flooding of their riverside property April 12, 2009. The gumshoe historian discovered no record that the water — which bled far up the banks and past her home in the middle of the night — had ever behaved this way in the last 162 years.

“That led me on a journey to find research and to learn about the area,” she said. “I made a promise to (my husband) to finish this work. He said, ‘We need to let people know that things went wrong here. We need to protect the environment.’”

Spellbound by maps of Manitoba’s watershed, Anderson wanted to figure out what caused the flood. Was it ice-jamming? The Red River Floodway? Heavy rains? A lack of dredging? Lake Winnipeg Regulation? A combination of each?

Manitoba Hydro introduced the Lake Winnipeg Regulation in the 1970s, to manage water levels like a hydroelectric reservoir. The Jenpeg generating station regulates 85 per cent of Lake Winnipeg’s flow via the Nelson River’s west channel at the most northern tip of the lake.

Regulation manages the water with the precision of one metre, almost like a weather report, up to 14 days in advance. Lake Winnipeg can expect water levels of 217.3 metres above sea level until the second week of May. To put this into perspective, Winnipeg sits 239 metres above sea level.

“If we need to utilize the lake, we need to look at ways we can change around some of the problems, and reconstructing that marsh is part of that solution,” Strang said. “We can still have our hydro and the warmth and the light and everything else, and we can still have a healthy marsh.”

The Red River Basin Commission and countless other organizations and communities are grappling to strike a balance between human intervention and natural cycles.

“You’ll never see a partnership like this. It shows people have come together to agree this is a really, really important issue — and that’s amazing,” Strang said. “The federal government has committed a lot of financial dollars to this project through the program. We’re hoping the province has the same passion.”

Strang and Goldsborough expect the current Netley-Libau Marsh pilot project to unfold over the next decade or two if all goes as planned.

“What we’re proposing here not novel; it’s not that it’s never been anywhere, it has,” Goldsborough said. “We are using a tried-and-true technology, but what we’re trying to do is determine if it will work here as well as it works elsewhere.”

fpcity@freepress.mb.ca