Winnipeg centre digs deep into Soviet files on missing Mennonites

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/09/2019 (2316 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Mennonite brothers Heinrich and Jacob Ivanovich Becker were deemed innocent of anti-Soviet Union crimes — but only after their executions in the name of such accusations during the Great Terror in 1937.

The former was charged with “systemic counter-revolutionary nationalist propaganda”; the latter: “anti-Soviet agitation.”

The truth behind their disappearances is dark, as are the stories of many Mennonites taken by Soviet Union forces during the 1930s and ’40s. After decades of wondering about what happened to their relatives, families are, at the very least, getting answers, thanks to the Centre for Transnational Mennonite Studies.

“People have lived with uncertainty for such a long period of time,” said Aileen Friesen, co-director of the centre at the University of Winnipeg. “What we’re trying to do is offer these people the chance to know what happened to their loved ones, if the information is available.”

The recently opened KGB archives in Ukraine detail what happened to Mennonites who were arrested over accusations that were trumped-up or falsified by Soviet leader Josef Stalin’s regime.

During that time, the local police (known as the NKVD at the time, later the KGB) had arrest quotas. Moscow pressured police to arrest suspected agitators and Mennonites fell under the German category. They did so based on “flimsy info” that was often invented, Friesen said. Authorities forced confessions and undertook subsequent punishments.

The Winnipeg centre will connect families with researchers who comb the files to find information about Mennonites who went missing in what is now known as Ukraine. Friesen found out the fate of the Ivanovich Becker brothers, who she believes are her grandfather’s first cousins.

The number of Mennonites who died from unnatural causes during the Soviet Union’s rule is uncertain. Historian Peter Letkemann estimates about 30 per cent of the 90,000 Mennonites in the region during the 1930s and ’40s died at the hands of tyranny.

Letkemann, who specializes in Russian Mennonite history, said police kept detailed records. Most of the information, however, was made up.

“What we’re trying to do is offer these people the chance to know what happened to their loved ones, if the information is available.”– Aileen Friesen, Centre for Transnational Mennonite Studies co-director

“We know that a lot of what is in (the files), the families should not believe. There are lots of important details, but you have to be able to read between the lines to sift out the details,” he said.

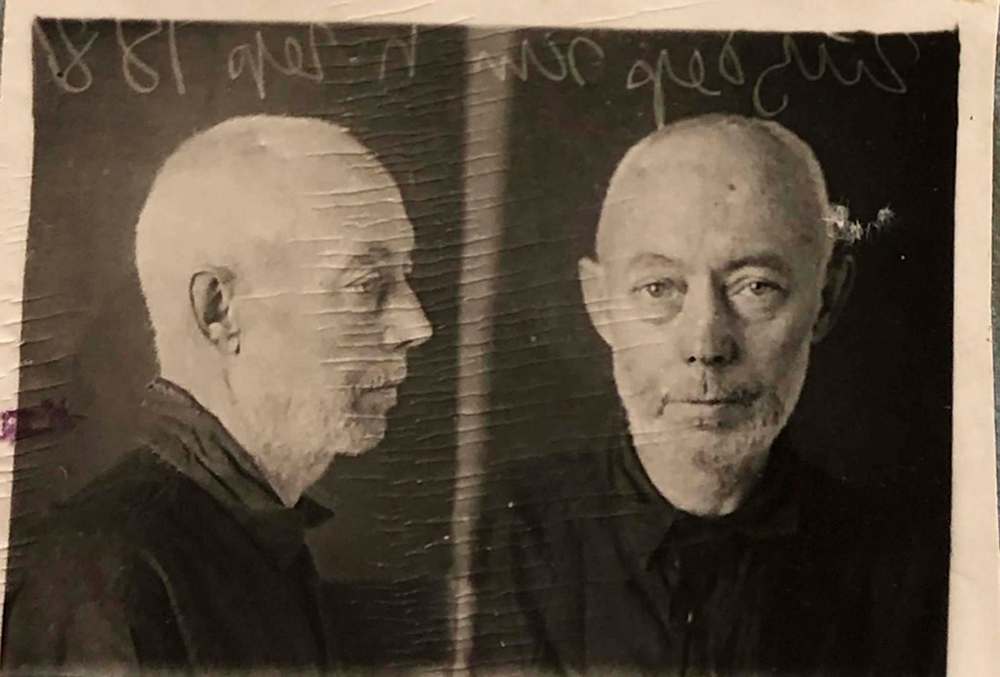

Among the files, there are interrogation transcripts, headshots and letters to authorities from families asking for answers. As well, there are documents about re-investigations into many of the cases undertaken in the 1950s. The Ivanovich Beckers were deemed innocent after the case was re-investigated.

The Centre for Transnational Mennonite Studies has received dozens of requests from families across the country since it started digging up files several months ago, Friesen said.

“It’s a very morbid experience. You see the disintegration of families as people are arrested, interrogated and taken away, sent to exile or shot. You see family members writing in to try to find out what happened,” she said.

In some cases, children were sent to orphanages if their parents were arrested and no one was willing to care for them out of fear, she said.

The research is being funded through the Paul Toews Fellowship in Russian Mennonite History, which also supports history conferences and other archival research in both Ukraine and Russia.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @macintoshmaggie

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., she first reported for the Free Press in 2017. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.