Curiosity is key in post-truth era

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/09/2017 (2965 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Scientists have stepped up their investigations into fake news in recent months, and amid all the analyses, studies and meetings, some have raised the possibility that a lot of people simply don’t care whether the claims they embrace are true.

“Post-truth” has become a hot topic for researchers from a variety of fields, including Nobel prize-winning chemists: the annual Lindau Nobel Laureate Meeting in Germany this summer took as a theme “Science in a Post-Truth Era.”

Skeptics have long studied why people wrongly believe in astrology, ESP and all manner of weird things, but not caring about truth at all would seem to fly in the face of basic human curiosity. People send probes to other planets, dig up dinosaur bones and build powerful microscopes to find out the truth about inner and outer space. We follow crime stories because we want to learn what really happened. Shouldn’t curiosity act as a guardrail to keep us from falling into a post-truth world?

Astrophysicist Mario Livio makes a key observation in his new book Why?: What Makes Us Curious: to be truly curious requires a middling level of knowledge. If you know absolutely nothing, then you don’t know what to be curious about. If you know everything, you have no reason to inquire. So children who have never heard of dinosaurs can’t be curious about them, and very few adults are curious about how many pennies are in a dollar.

However, it’s not actual knowledge but people’s perception of their own knowledge that encourages or stifles curiosity. Vladimir Putin biographer Masha Gessen noted that one striking similarity between Putin and U.S. President Donald Trump is their utter lack of curiosity; she said that both men think they already know everything. That perception of superior knowledge comes through in Trump’s habit of saying “Nobody knows it better than me” when discussing a variety of subjects — taxes, trade, visas, infrastructure, social media, uranium sales and “nuclear horror,” to name a few.

So curiosity requires a level of humility. But how far does the problem of ego inflation go? In his new book The Death of Expertise, author Tom Nichols makes a case that there’s a raging epidemic of egomania in the United States. “Most cases of ignorance can be overcome if people are willing to learn,” he writes. “Nothing, however, can overcome the toxic confluence of arrogance, narcissism and cynicism that Americans now wear like a full suit of armour against the efforts of experts and professionals.”

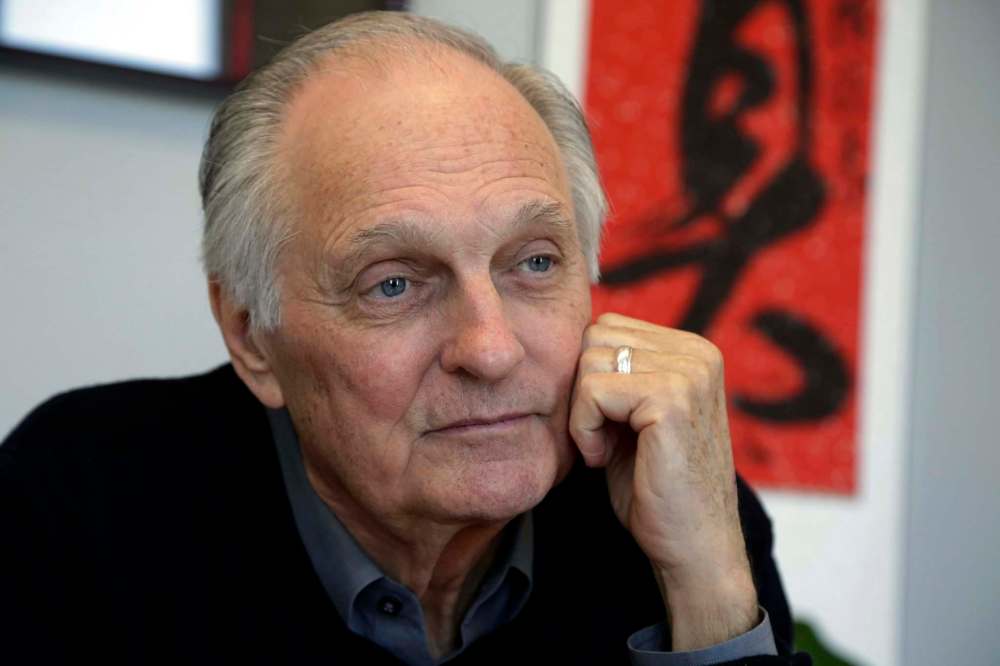

Of course, not everyone takes such a dim view of human curiosity. In another book about expertise, If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face?, the actor and science advocate Alan Alda takes for granted that many people are hungry for knowledge. But to engage that curiosity, he argues, experts have to pay attention to their audiences to gauge where they fall on that spectrum of intermediate knowledge.

Alda is himself a curious character. He became involved in science communication after hosting the television show Scientific American Frontiers. He realized that scientists often find themselves onstage or in front of cameras struggling to explain their research, and thought his expertise in acting and improvisation might prove useful. Now he’s adapting his ideas for business leaders and other experts.

One lesson from improvisation, he says, is that real communication is an exchange, and what you say should depend on what you see and hear from the other party. Everyone knows things you don’t know — whether you’re speaking to an astrophysicist or the person who cuts your hair or delivers your pizza. They have different experiences. They’ve seen the world from different angles. If people can engage their curiosity, it doesn’t matter who is smarter. What matters is that both parties leave the encounter smarter than they were before.

William Moerner, a Nobel laureate in chemistry, is one of those curious people. I was interviewing him about various topics after he had spoken at the meeting of Nobel winners in Germany, when the U.S.’s decision to cancel a national commission on forensic science came up. He wanted to know what I knew. He had a notebook and pen in hand, and by the end of our chat, he may have asked as many questions and jotted as many notes as I had.

While he’d been onstage during the panel discussion, another journalist asked him why he wasn’t more outraged, given the way the U.S. government was sidelining science. Indeed, the world (and especially the world of social media) seems to demand indignation. But outrage hinges on certainty — not on that intermediate level of knowledge that stimulates investigation and curiosity. Moerner’s response? At times like this, he said, “Someone needs to be rational.”

Faye Flam has written for the Economist, the New York Times, the Washington Post, Psychology Today, Science, New Scientist and other publications.

— Bloomberg