Taking a journey to the distant past

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/04/2025 (188 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

We are looking at rudimentary tools fashioned by human hunter-gatherers tens of thousands of years ago, when they sheltered in caves on Italy’s heel.

I say “rudimentary,” but what a breakthrough those implements must have been — flint and limestone honed to points and used for myriad things: hunting spears, knives to flay animal skins, tools to perforate and engrave clothing and other objects. Their work has a simplistic beauty you can’t help but admire, revealing an impressive ingenuity.

The leg bone of a hippopotamus, the jawbone of a horse and a deer antler are remnants of some of the creatures the Neanderthals hunted and ate.

Pam Frampton photo

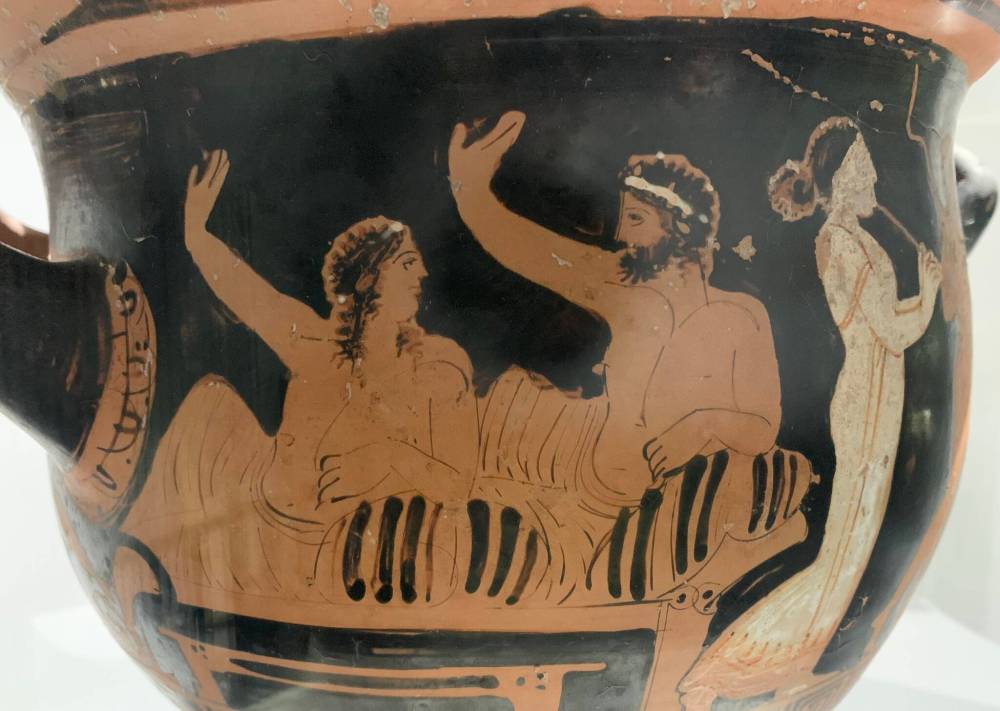

Elaborate drinkware from 2,000 years ago.

My husband and I are at the Museo Sigismondo Castromediano in Lecce — the oldest public museum in the region of Puglia — founded in 1868 and home to a host of archeological treasures.

The objects here tell the story of how human civilization unfolded in southern Italy, from primitive terracotta toys to elaborately painted burial urns. The age of the artifacts is astounding, particularly to someone who lives in St. John’s, N.L. — a city that considers itself old in terms of European settlement.

It is fascinating to think of these archaic humans sitting around a fire in a cave (much as we sit transfixed in the glow of our cellphones), the flickering flames illuminating stone walls, where perhaps someone has left their mark in charcoal. They could not possibly imagine how the world would change with the passing centuries, but change it did.

Here in the museum, we can see how tools became more complex, how play was encouraged, how art became more elaborate.

There are elegant clay amphorae, used to transport wine and olive oil across the sea. They are unadorned except for those pulled from the holds of long-lost ships, where they became part of the ocean floor, encrusted with barnacles and coral.

An array of small clay jugs and oil lamps in a glass display case is especially poignant if you think of the many human hands that held them. They are vessels that had been left as offerings at an altar near the sea, along with people’s hopes for their loved ones’ fruitful and favourable voyages.

Pam Frampton photo

Small clay jugs and oil lamps were often left as offerings to the gods.

With the passing of centuries, containers became more elaborate. There are ceramic plates, bowls and vases painted to tell ancient stories of gods and goddesses and of human life and death: feats of athleticism and bravery in battle, rituals of burial, celebrations with music and feasting.

Household items are functional, but also works of art.

A plate from the fourth century B.C. has been painted with a pattern of spiny fish. A Bronze Age pan has a handle sculpted in the form of a nude male. There is an ancient turtle carapace that was used to make the body of a lute.

Vases and drinkware from more than 2,000 years ago are fashioned like the heads of gryphons, horses, bulls and humans, and intricately painted.

On one large double-handled vase, a man wearing a toga and helmet offers an elegantly robed woman a beaded necklace; an egret-like bird stands in the background. The detail and decorative elements are stunning.

Pam Frampton photo

A musician entertains as a couple relaxes on a divan on a piece of ancient pottery.

Leaving these wonders behind and stepping back out into 2025, it is hard to reconcile the evidence of progress and sophistication I’ve just witnessed with the rampant backwardness of today’s world.

Women in Afghanistan subjugated, silenced and hidden. Homosexuality criminalized in several countries and, in some, punishable by death. Vulnerable people trying to flee unrest who are then trafficked as slaves. Children killed as casualties of terrorism and war. Pedophiles trolling foreign countries for minors to sexually assault and exploit.

Russian dissenters mysteriously plummeting from balconies.

Countries being run by narcissists and oligarchs masquerading as defenders of freedom, who would stifle and control the free press.

I think of U.S. President Donald Trump and his relentless quest for “greatness” — for himself, at least; eyeing other sovereign nations and territories as potential assets just waiting to be gobbled up.

Pam Frampton photo

An ancient vase records the bestowing of jewelry.

I think of Elon Musk, the self-styled bastion of free speech, cancelling people on his social media platform when he doesn’t like what they have to say.

I think of Trump and his cronies trampling upon trans people’s identities, LGBTTQ+ rights, gender equality, women’s reproductive rights and diversity and inclusion policies like a herd of elephants gone rogue.

I think of migrant children in America —the “huddled masses,” the “homeless, tempest-tost,” once welcomed by the Statue of Liberty — now without legal counsel thanks to legal aid funding cuts ordered by Trump.

I think of all these things, of how a few rich and powerful people seem intent on impeding social progress, turning back time and widening the chasm between themselves and the rest of us, and I despair.

Pam Frampton is a writer and editor in St. John’s.

Pam Frampton photo

Primitive tools developed by Neanderthals between 10,000 and 40,000 years ago, and the bones of hippo, deer and horse.

Email pamelajframpton@gmail.com

X: pam_frampton | Bluesky: @pamframpton.bsky.social

Pam Frampton is a columnist for the Free Press. She has worked in print media since 1990 and has been offering up her opinions for more than 20 years. Read more about Pam.

Pam’s columns are built on facts, but offer her personal views through arguments and analysis. Every column Pam produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.