This is what I want you to know

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

I sometimes stand on the third floor of the former Portage la Prairie Residential School, where hundreds of children stood before me, and look out over the grounds and the lake beyond.

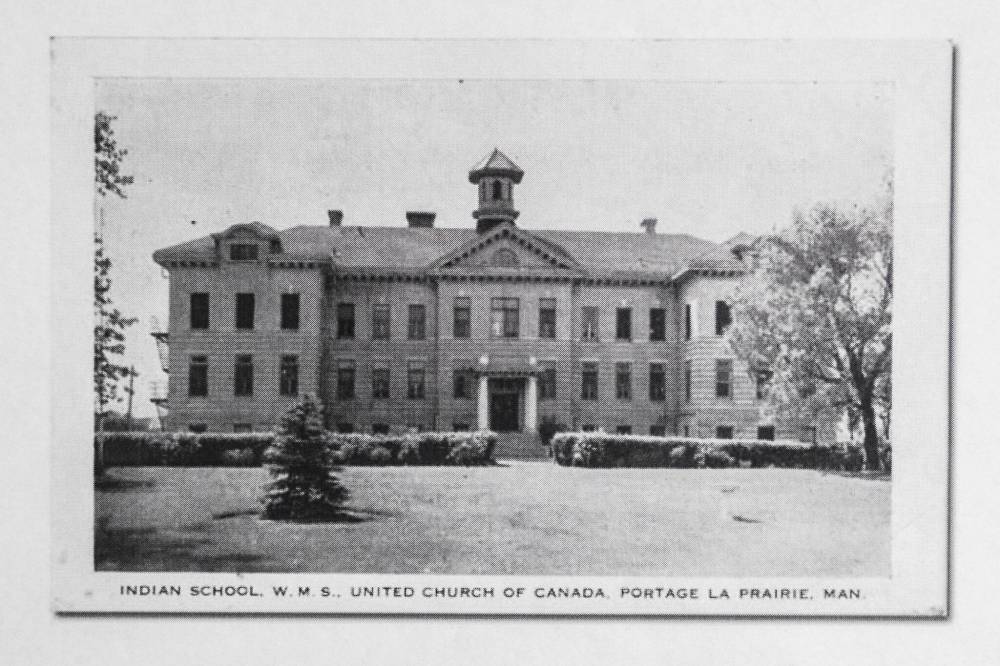

Fifty years ago this year, the Portage la Prairie Residential School closed. But the building still stands, holding the history of all the children forced to attend. Today, it is home to the National Indigenous Residential School Museum of Canada, where I serve as executive director and share my own personal experiences as a residential school survivor.

I didn’t go to school in this building, but both of my parents did. I went to residential schools in Brandon, Sandy Bay, and Birtle. Each of those schools changed me, taking from me my language, my culture, my loved ones, and my youth.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / FREE PRESS

Washrooms in the basement of Portage residential school in Portage la Prairie

But the school in Birtle took something deeper, and left something emptier.

When I think of that school, I feel a emptiness. It was cold at the Birtle Residential School, not just in temperature, but in spirit. No love. No comfort. Just fear and rigid, harsh rules. I remember being sick, really sick. Sweating, weak, running to the bathroom constantly.

I was begging for them to call a doctor and they didn’t. I don’t know what it was — a flu, maybe appendicitis — but I do know they didn’t care enough to find out. It was just neglect, which was normal there.

There was one moment of peace I still remember while at the Birtle Residential School: a little stream outside. We’d take our shoes off, play in the creek. For a few minutes, we could just be kids. Free. That little bit of nature was the only place I felt like myself.

Because at Birtle, I wasn’t Lorraine or the nickname my family gave me, Onzaamidoon, which my aunties called me because I talked too much. I wasn’t a granddaughter who learned medicines from her grandmother or picked berries. I was just another number.

That’s what residential schools did. They stripped away names, languages, family, and caring. And replaced it with silence.

Now, 50 years after the closure of the Portage school, I help run a place that does the opposite.

I’m so encouraged to hear about new funding to help the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation find its permanent home. Every investment in truth and reconciliation lifts us all.

This is also a moment to recognize spaces like the National Indigenous Residential School Museum, where a small, dedicated team is preserving history in the very building where it happened.

This museum provides a unique experience for every visitor.

You stand in the same dormitories as the children did. You climb the same stairs. You look out the same windows. You feel the weight of what happened here.

And people do feel it. Survivors. Families. Visitors from across Canada and around the world. Some cry before the tour even begins. Because the truth lives in these walls.

FILE

A historical photo of the former residential school at Long Plain First Nation, which has now been designated a National Historic Site, near Portage la Prairie.

And yet this place isn’t just about sorrow.

It’s about turning a place of hurt into a place of healing, and sharing the strength it takes to carry memory forward. Not just for ourselves, but for the generations to come.

We are still here. The building is still here. And the stories are still here.

So this is what I want you to know, 50 years on: We are still here, doing the hard work of reconciliation.

While much work remains to build the National Indigenous Residential School Museum of Canada into the essential institution for Canada that it deserves to be, by working every day to transform this former residential school into a museum, we know we can further the work of reconciliation in Canada in a uniquely powerful way.

So come and visit us on the Keeshkeemaquah lands of Long Plain First Nation, near the city of Portage la Prairie. See what happened. Come feel what still lingers and witness the truth, not on a screen but in the very place where it happened.

On Tuesday, the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, we will welcome Phyllis Webstad (who started Orange Shirt Day) to the museum to share her story, as well as the stories of many survivors. Everyone is welcome. For those that can’t travel, there are many great events happening all around Manitoba and I encourage you to find one close to you and participate.

Because reconciliation cannot exist without truth, and truth begins with the stories of survivors and lives on in the walls of this museum.

Lorraine Daniels is executive director of the National Indigenous Residential School Museum of Canada.