Why race to the moon?

Because its surface holds enough helium-3 to generate electricity for '10,000 years'

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/09/2009 (6008 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The race is on to return to the moon, and this time America has a new set of rivals: Japan, China and India. At stake is access to a new and clean source of energy buried in the grey lunar soil — helium-3, which could be used to power fusion reactors in the near future.

NASA intends to send astronauts to the moon by 2020 with the Constellation Program, the replacement for the space shuttles. The Ares I rocket will bring astronauts up to Earth orbit where their capsule will rendezvous with a lunar lander launched aboard the massive Ares V. The combined ship will then take off for the moon. NASA plans to eventually establish lunar bases.

This ambitious plan is attracting criticism and already running into trouble.

Although the space shuttles are expected to be retired next year, the Ares I won’t be ready until 2015 — just before the planned end of the space station project. In the interim, America will have to send its astronauts up on Russian spacecraft.

A presidential review of American human spaceflight plans has just reported that NASA has inadequate funds to reach the moon by 2020. About 10 years later could be more realistic. The report also casts doubt on using the two different Ares rocket systems to replace the shuttle, and it states that the Ares I will probably be delayed until 2017.

This confusion and uncertainty are eroding America’s leadership in space and being met with serious competition from Asia.

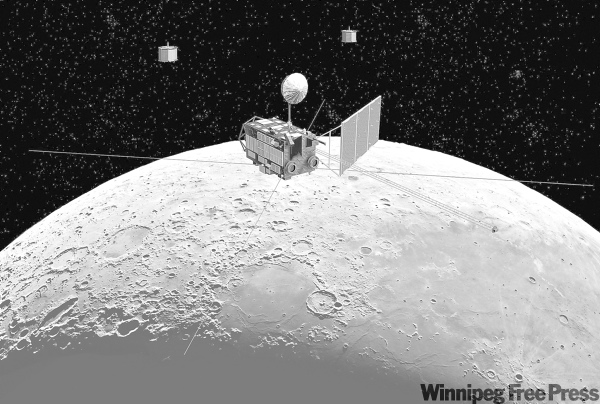

The Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has announced plans to put an astronaut on the moon by 2030. Japan is paving the way for this mission with its Kaguya spacecraft, which has been orbiting the moon since October 2007, taking high-definition images of the surface and, along with two smaller probes, obtaining data to answer questions about the formation of the moon. This mission will be followed in 2015 by Kaguya 2 for further investigations with a rover on the surface.

Japan has significant manned spaceflight experience. Six of its astronauts have flown aboard the space shuttles, and one of them has spent 4 1/2 months aboard the International Space Station.

Japan is also the only Asian partner in the space station. It has gained useful experience from its contributions to the project.

China is another strong challenger to NASA. Its Chang’e 1 satellite orbited the moon for 16 months, mapping the landscape and resources before crashing into the surface in March. This was the first step in China’s three-stage moon project. The next one involves landing a probe on the surface by 2012, followed by the final stage of putting a rover there and bringing back rock and soil samples by 2017. China, which has expressed a strong interest in putting a man on the moon, is the only Asian nation to have launched its own astronauts into orbit, having done so with three times since 2003.

The Indian Space Research Organization, meanwhile, has proposed putting an astronaut in orbit by 2015, will soon establish an astronaut training centre and already is talking about an eventual manned mission to the moon.

India’s Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft slipped into lunar orbit last November. Until contact was lost last month, the satellite investigated the distribution of chemicals and minerals and mapped the entire surface to a resolution of five to 10 metres. India reached out and touched the lunar surface by intentionally crash-landing a small probe from its orbiter.

The multinational probes orbiting the moon have been searching for water and useful minerals to locate ideal spots for bases. These surveys are also uncovering a resource so valuable it could justify lunar mining: helium-3. This special form of helium could be used for nuclear fusion.

Unlike conventional nuclear reactors that split uranium atoms, fusion reactors — currently in the experimental stage — combine smaller atoms like hydrogen.

If nuclear fusion becomes a viable source of energy, helium-3 will be an ideal fuel. When used with deuterium (a type of hydrogen), only low-level radioactive waste is left behind from side-reactions. Helium-3 is a compact, relatively clean and powerful energy source.

Carried away from the sun with the solar wind, helium-3 is very rare on Earth because it is deflected by the planet’s magnetic field. On the unshielded moon, however, it has accumulated in the lunar soil over the eons, ready to be scooped up, processed and brought to Earth.

Just a few a tonnes of helium-3 would satisfy the energy needs of Canada for a year.

Although practical nuclear fusion could be decades away, it makes sense to start developing the capability of getting to the moon to collect helium-3 for the reactors of the future.

The Japanese, Chinese and Indian space agencies have acknowledged the importance of obtaining helium-3 from the moon. All of these nations are also investing in fusion research. They are partners in the seven-member International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor project, and Japan and China have developed their own experimental fusion reactors.

China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency quotes the chief scientist of the nation’s lunar program, Ouyang Ziyuan, as saying, “We will explore the new energy prospects on the moon for mankind… When obtaining nuclear power from helium-3 becomes a reality, the resource on the moon can be used to generate electricity for more than 10,000 years for the whole world.”

China, Japan and India have good reason to explore fusion and to ensure access to lunar helium-3 fuel. After America, these countries are the second-, third- and fifth-largest oil consumers in the world. By 2025, America and its Asian space rivals are predicted to be the top-four net importers of oil.

While this second race to the moon might seem like a step backward (after all, it’s been done before), it could in fact be a bold leap toward a clean energy source to save Earth from more global warming.

Such common interests and the astronomical costs of space travel could prompt international co-operation in reaching the moon. The U.S. human spaceflight review recommends that NASA explore space with international partners. This could make more resources available and benefit foreign relations.

As China, Japan and India also come to realize the true costs and challenges of establishing separate lunar programs, they might agree to a collaborative effort with America. Fortunately, an excellent example of international co-operation in space already exists: the space station.

Tom Simko, an engineer living in Brockville, Ont., writes about space for the Winnipeg Free Press.