The killing cold

Few shelters, safe places to thaw leave Winnipeg's most vulnerable out in bitter temperatures

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/01/2018 (2877 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

I do not know what it’s really like to die in extreme cold, though many websites explain everything there is to know. They all read the same; curious and untroubled with titles such as “Why Freezing To Death Makes You Want To Get Naked.”

So many stories emphasize this, the strangeness of dying in the cold. Morbid curiosity seizes on terms for these actions, the desperate last acts of a body coming undone. “Terminal burrowing,” for instance, or “paradoxical undressing.”

“People suffering from hypothermia have been known to exhibit some bizarre behaviours that may… be a last-ditch effort to survive,” an article on LiveScience explains, next to a link entitled “15 Weird Things Humans Do, and Why.”

None of that really speaks to the slow horror of dying from cold. Maybe there is no way to describe it. Maybe we do not really want to know the last thoughts of someone who is out there, without hope, without any clear way to get warm.

Maybe the only thing strange about dying in the cold is that, in a city full of warmth, it happens at all.

We lost someone in the cold last week. Her name was Windy Sinclair. She was 29 years old and a mother of four children, and while those facts inadequately describe a whole person, here are three other things that we know.

Her family loved her, she struggled with addiction and she died alone close to Christmas in a frigid back lane.

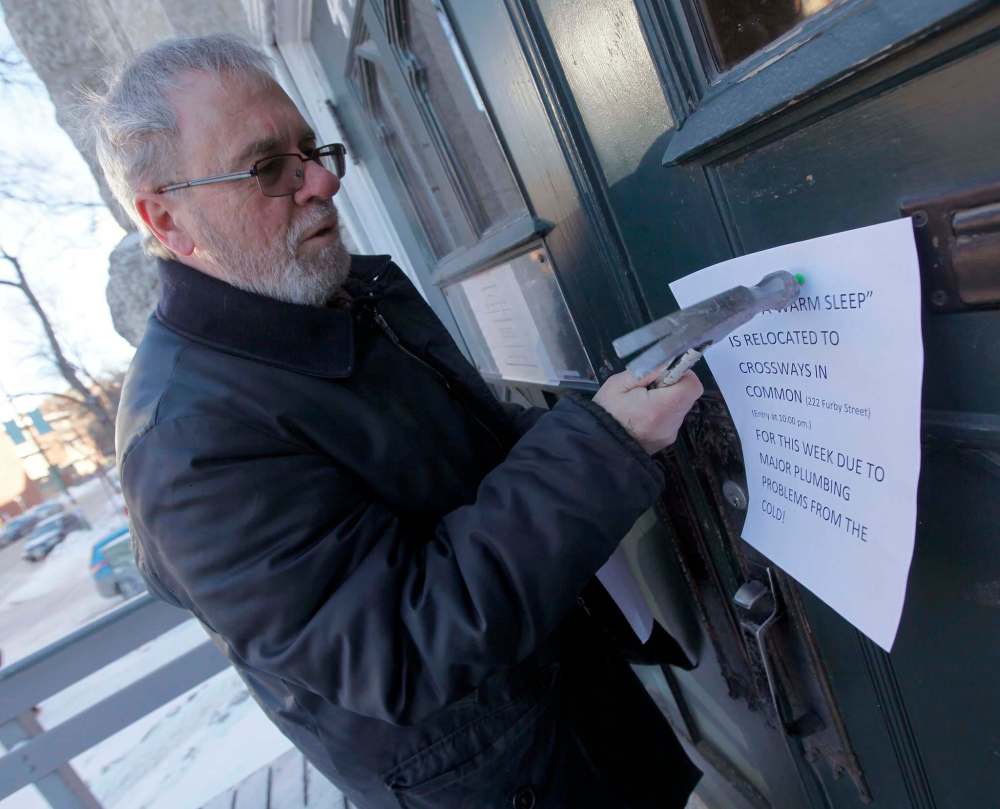

There are things we don’t know about her. We don’t know how she ended up in that Furby Street spot where her body was found, 10 kilometres south of Seven Oaks Hospital, where she’d been taken in distress on Dec. 25.

We don’t know how she slipped out of the hospital, even as she was slated to receive treatment. And we do not yet know for certain that she died of hypothermia in the -30 C weather; an autopsy was pending as this was being written.

But whether she froze to death or simply died freezing, what happened to Sinclair brings into focus the cold, hard facts of this city and demands we contend with the resources, or lack thereof, to ensure we all can get warm.

For instance, Winnipeggers didn’t know about Sinclair’s death until Wednesday, when police confirmed it after a Free Press inquiry. Are there other people found frozen on our streets whose stories are not known, not released?

Perhaps we should have a public accounting. This is Winnipeg after all, the wind-ravaged winter city. The human cost of the cold is something we should fully understand. Without knowing that, how can we deal with what it means?

Yet, in a way it’s a wonder that more of us don’t freeze to death on these streets. For that, we can credit local shelters and all places of refuge, large and small. These are the beacons on the front lines, critical bulwarks against the perilous cold.

Macdonald Youth Services runs an eight-bed emergency shelter for youth. Siloam Mission sleeps 110, and Main Street Project, 85. Last year, Augustine United Church started opening its doors for people to sleep on cold nights.

These are just some examples. But all places of refuge have limitations, by size or location or disposition. Siloam Mission, for example, is a dry shelter and does not accept people who are intoxicated; Main Street Project does.

And throughout the winter, people shuffle between them just trying to stay alive and stay warm.

“There is a migration visible every day in Winnipeg, particularly in the winter,” Nancy Chippendale says. “It’s very much people finding warm shelter and places they’re welcome, places where they can be a part of a community.”

For years, Chippendale has championed the safety of Winnipeg’s homeless people. She is passionate, a longtime community activist — she helped spearhead the effort to get Canada Post to sell land adjacent to Gordon Bell High School so it could be turned into a sports field — and this issue has gripped her.

In fact, one day before Windy Sinclair began to die in the cold, Chippendale was tweeting about the problem.

“I would like to call out to the mayor of Winnipeg to open its first emergency warming centre today to help save lives of so many with addictions denied entrance in this freezing cold,” she posted on Christmas Eve. “Will you join me?”

The cold, Chippendale points out, is like a natural disaster. But it is not like hurricanes or wildfires, which consume everything they encounter. Cold is selective, unequal. It devours only those among us with the fewest resources.

For Winnipeggers with warm clothes and secure housing, the cold is mostly an ill-mannered visitor. We complain about the weather and scrape frost off car windows, pausing to commiserate with a neighbour: “Cold enough for ya, eh?”

Yet for people lacking those basic comforts, cold like this — cold that kills, cold that ends worlds — is indeed a disaster. That it comes every year does not reduce its damage; it only emphasizes more that we must take defensive action.

It is not just Winnipeg that wrestles with this. In Toronto, the city ombudsman has opened a review of “confusion” over the city’s available shelter beds after reports of people being turned away from full shelters in the killing cold.

To close the gap, activists there have taken up the cause, demanding more emergency shelters. Every day people stepped up to book hotel rooms for people needing a warm place to sleep. Their voices are being heard.

In Winnipeg, Chippendale proposes a few clear-cut actions.

First, she would like the mayor and city councillors to regularly tweet information about available shelters, including which are at capacity. Second, she would like the city to publicly release information about people who die in the cold.

And third, she champions the creation of emergency 24-hour warming centres. These would be something short of a full shelter, just a place for folks to go: somewhere with a pot of coffee, a welcoming smile and a safe spot to get warm.

Would a place like that have saved Windy Sinclair? We don’t know.

But this much is certain. There are people outside today with no money and comparatively few places to go, locked in a daily battle to survive in the bitter cold.

They shouldn’t have to be. None of Chippendale’s ideas are particularly daunting or unreasonable; they are all things we can do right now, given the public will to do so. They are things that might save a life, a limb or just a bit of hope.

Winnipeg is, above all, a city of warmth. This much I know to be true. None of us should be left in the cold.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.