Caring mission in core is gone

North End facility can't make ends meet

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/12/2010 (5526 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

There have only been two permanent residents of 470 Stella Ave., the century-old building that has stood on its stone foundation as an outpost of social justice and sanctuary for the poor.

One is Hope.

The other is Comfort.

But now it appears the people who live in one of the most impoverished and crime-blighted ‘hoods in Canada are going to have to look for both of their longtime neighbours somewhere else.

Hope and Comfort don’t live there anymore.

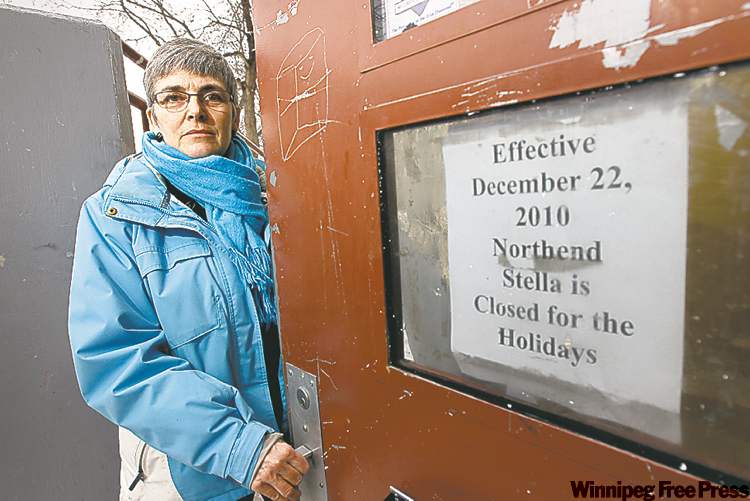

The sign at the door may say “closed for the holidays,” but there’s something missing.

A reopening date.

That’s because a year after celebrating its 100th anniversary, and a mere two months after a series of deadly random shootings that made national news, historic Stella Mission has closed its doors.

Probably, by the sounds of it, forever as a United Church mission.

It appears the collection plate alone just won’t cover the costs anymore.

The building is one of a cluster of missions founded in the North End at the first light of the 20th century by the Methodist Church. Initially known as the All People’s Mission, it has been a place the city’s socially disadvantaged have come to in search of community, food, God and even English-language lessons. The renowned social-democratic politician and clergyman J.S. Woodsworth tended to the flocks of eastern European immigrants who arrived in the city’s North End during those early years.

Last October’s bloody spree of still-unsolved shootings — which left a 13-year-old girl severely wounded and two men dead and had police warning neighbourhood residents to stay off the streets and not answer their doors to strangers — had nothing to do with why the building has locked its doors, apparently forever.

It doesn’t necessarily mean some of the mission’s work won’t carry on out of different locations in the North End, although, clearly, the mission won’t be able to do it as fully and well without a place of its own that signals its purpose.

“We’re absolutely committed to be here,” the mission’s minister, Rev. Adel Compton says. “But, we can’t do it in the building without some help.”

An inability to fund the more than $200,000 budget is the issue.

The violence, though, and how people turned to the mission for support, do point to why a building with so much history of offering comfort and hope is so important.

“We’ve been a warm, safe place for people to drop in for 100 years,” Compton says.

That was never more true, perhaps, than in the days following the sighting of a person dressed like a Ninja warrior and riding a bike just before the sounds of shooting and a girl’s screaming.

“We see literally hundreds of people every month,” Compton says, still using the present tense.

They came for crisis support.

They came for coffee.

They came for monthly suppers provided by United Church members.

They came to use the mission’s three community computers.

They came for church services on Monday nights. They even came just to use the telephone because they don’t have one themselves and they could get a callback there if they were looking for work.

And if they were young mothers, they came for the respite daycare services that offered them some time to themselves.

“Unfortunately,” says Compton, “if we’re not here, we can’t do those things.”

It’s not surprising that it was poverty — the social virus that’s seemingly endemic to the neighbourhood — that eventually claimed the mission’s building, if not all of the mission’s work.

But it’s not the only reason the United Church seems to be struggling, and has started a fundraising website — 1hopewinnipeg.com — to help maintain a network of five outreach missions in Winnipeg.

Money is simply the most obvious issue. The other is the rise of socially conservative evangelical churches, both in numbers and influence, and the decline of aging social-democratic faiths such as the United Church.

Nowhere is that more apparent than in the fist-fuls of dollars that several levels of government granted Youth for Christ for its Centre for Youth Excellence, which is also a mission. The difference being — beyond money — that it’s aimed directly at converting aboriginal at-risk youth to Christianity by attracting them with a $13.5-million state-of-the-art recreational facility.

The United Church learned the lesson about the inherent danger of that approach during the residential school tragedy. That’s why the United Church missions in Winnipeg have a Two Paths One Journey approach that honours and includes aboriginal culture and spirituality by addressing racism, poverty and residential school issues.

That doesn’t pay the bills, or attract big donors. Not the way Youth for Christ does.

As I’ve written before, systematic conversion — and resulting subjugation of First Nations culture and religion — by Ottawa-backed Christian organizations has a painful history in this country. Inner-city youth desperately need alternatives to street gangs, but those alternatives should not be delivered by people who want their souls in return.

It appears that, unfortunately, the Youth for Christ facility will be where people find Hope and Comfort now.

But at what cost?

gordon.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca