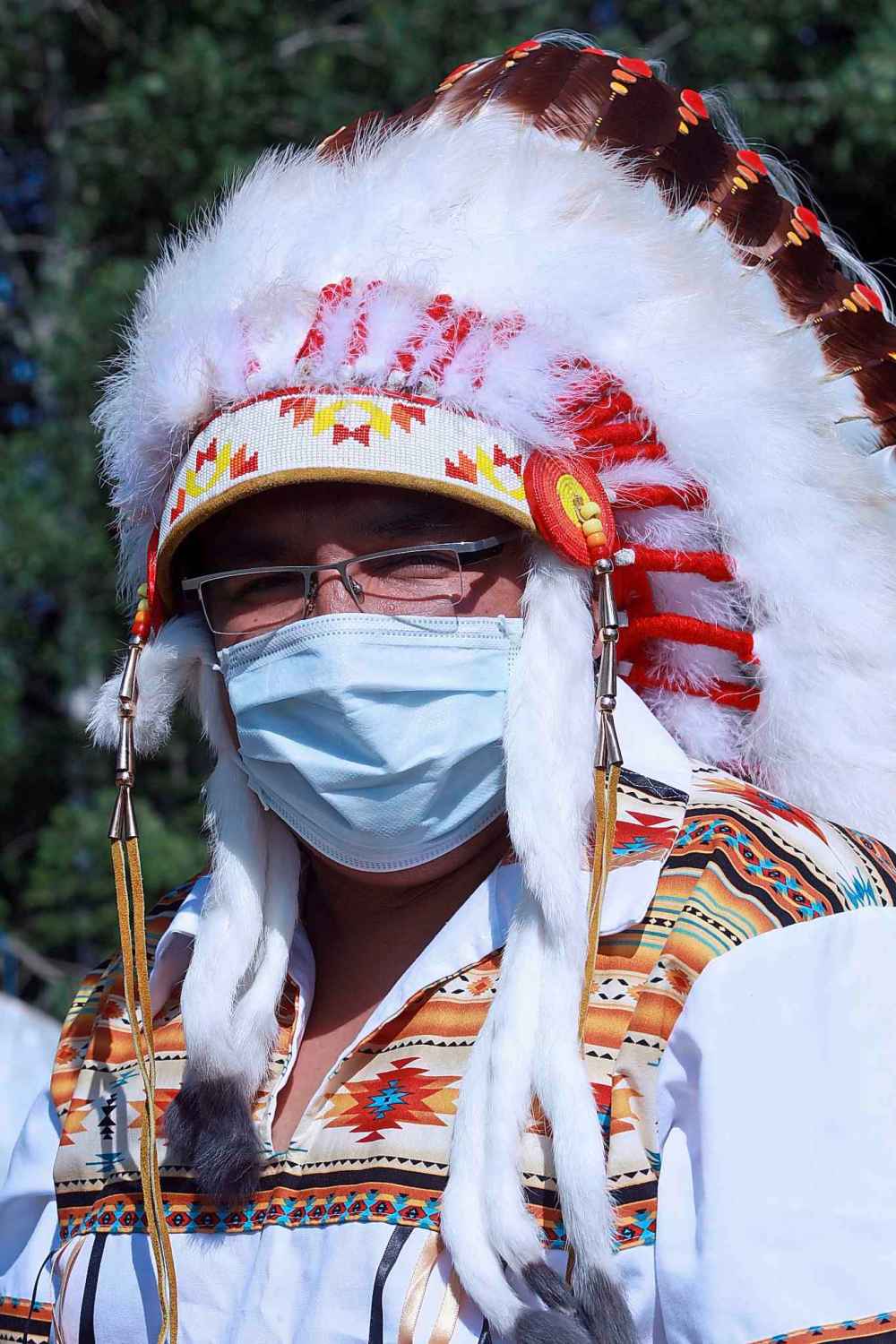

Pandemic plans lacking in Indigenous communities

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/03/2020 (2067 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

During the first wave of the H1N1 influenza pandemic in Canada (April-August 2009), Indigenous peoples accounted for nearly 46 per cent of all sickness-related hospital admissions.

Despite making up less than five per cent of the nation’s population, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples also represented 18 per cent of all confirmed H1N1-related deaths in those early months, according to research published in science journal PLOS One. (The nation’s total in 2009-10 was 428, on more than 33,000 cases, according to Infection Prevention and Control Canada.)

Years later, researchers pointed to poverty as the main culprit, leading to a proverbial “perfect storm” of overcrowded and unsuitable housing, poor education and employment, and compromised health and immune systems due to the absence of suitable food and drinking water.

Add in the absence of basic medical and support services in remote and urban Indigenous communities, and the overwhelming number of H1N1-infected Indigenous peoples makes sense.

Things got so bad in 2009, federal officials shipped the remote reserve communities of Wasagamack and God’s River First Nation body bags, alongside hand sanitizer and face masks, leading Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak then-grand chief David Harper to ask media if Canada had given up fighting the virus in Indigenous communities.

“I make a plea to the people of Canada to work with us to ensure the lowest fatalities from this monster virus,” Harper said at the time. “Don’t send us body bags. Help us organize; send us medicine.”

It’s now 2020, and a new “monster virus” has arrived: COVID-19.

It’s transmitted mainly through respiratory droplets produced when an infected person coughs or sneezes, entering another person’s mouth or nose. It can also travel via touch contact with contaminated surfaces or objects, then touching the mouth or nose.

In other words: the same as H1N1. It’s not a matter of if Indigenous peoples are going to be impacted by COVID-19 but how much.

Since 2009, not much has changed for the Indigenous population: the Indian Act is still in effect, poverty remains at a record high, and most of the poor conditions in housing, education, employment, and lack of adequate food and water are still present.

What’s changed, for the most part, is experience. Since 2009, most Indigenous governments have developed plans to deal with pandemic events.

In early March, Nunavut’s Department of Health issued protocols on how it intends to deal with COVID-19 — one of the first Canadian public agencies to do so. The move came from Nunavut’s 2009 experience, and its long history of tuberculosis epidemics in the region.

The federal government has also learned in the past decade.

One of the primary issues leading to the viral spread of H1N1 lay in the ways First Nations receive health care (federally under the Indian Act, instead of provincial, like for all other Canadians), leading to a delay in the shipment of masks, respirators, and hand sanitizers. There was also a racist belief amongst federal bureaucrats (as media reported at the time) sending alcohol-based sanitizers would promote addiction and cause death.

There are signs these problems have been addressed. During Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Wednesday announcement of $1 billion to “pull out all the stops” and combat COVID-19, he included $200 million for federal medical supplies for Indigenous communities.

Federal money has also been made available for Indigenous researchers to study Indigenous-specific issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

On March 6, three University of Manitoba researchers received nearly $1 million in funding to study how COVID-19 is impacting Indigenous communities. Unlike 2009, when research took place after H1N1 was under control, Drs. Michelle Driedger, Stephane McLachlan and Myrle Ballard will work in real-time, providing recommendations to Indigenous leaders and federal officials.

The researchers will be focusing on Indigenous communities in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and northwestern Ontario, and hope to collect data and provide workshops and training starting in two weeks.

The clock on the virus’s arrival, though, is ticking.

Dealing with COVID-19 requires specific knowledge and sensitivity, regarding the ways Indigenous peoples live culturally and socially. Everyday instances such as feasting, visiting, and gift-giving all are a part of Indigenous life — particularly in the North.

“All it will take is one infected person to arrive in one community with a closed winter road, and we could see infection travel quickly,” Ballard said in an interview. “That is how close we are to an emergency situation.”

The communities need support in updating pandemic plans; most lack the infrastructure and backing to keep their stocks of health supplies consistently ready.

“Attention must come right now to help those who will be most impacted by COVID-19,” Ballard said. “In most cases, this will be Indigenous peoples.”

This time around, though, let’s send medicine, not body bags — and fight this together.

niigaan.sinclair@freepress.mb.ca

Niigaan Sinclair is Anishinaabe and is a columnist at the Winnipeg Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.