Museum opening may silence critics

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/09/2014 (4125 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Like a freshly opened bottle of fine red wine, people need to give the Canadian Museum for Human Rights a little time before passing judgment. Let it open; let it breathe.

Some of the museum’s content will be controversial, both for what it includes and what it leaves out. For what it says and doesn’t say.

The museum should be responsive to criticism and prepared to make corrections or modifications as it evolves over time. Indeed, the CMHR does not want to be a static institution that never changes. New research and new thinking will inevitably lead to different presentations and interpretations; scholars and others will debate concepts and challenge conventional wisdom.

All of that is as it should be.

Bullying, however, is not.

That includes the threat of boycotts, which two groups have already declared; one by the Manitoba Metis Federation in a dispute over opening ceremonies, another by a coalition upset about the square footage dedicated to the issue of internment camps during the First World War.

No one, including any political party, should resort to strong-arm tactics to influence the content of an institution dedicated to the promotion of open and civil discourse. There is no evidence of undue political interference, but the risk is always there.

Unfortunately, there is still a lot of confusion about the museum’s purpose. It’s a problem that has dogged the museum since it was first proposed by the late Izzy Asper in 2003.

It is not a genocide or history museum. It is certainly not a place where every victim-group gets an equal opportunity to tell its story. It is not even a museum, at least not in the traditional sense.

The CMHR is primarily an educational facility that aims to teach visitors about human rights. The goal is to compel people to examine their own records and attitudes.

Ideally, visitors will feel motivated to make a difference in their communities, as opposed to being passive bystanders.

Some groups are upset about the space allotted for their cause, but after experiencing the museum in full, they may well reconsider their positions.

Some Ukrainians say their stories aren’t properly represented, but you can be sure other groups will feel they are ignored altogether.

The right-to-life movement could argue, for example, that abortion is the greatest atrocity in history, but it’s unlikely they will have their own gallery, if any space at all.

It’s the kind of divisive issue, like many current events, that is best handled through seminars and panel discussions.

Historically in Canada, the list of victims is nearly endless. In fact, Anglo-white protestants, at least those outside Quebec, are the only group that can’t make a convincing case for human-rights abuse, although women and homosexuals of any background have a claim.

Worldwide, the catalogue of human rights atrocities is off the scale.

The museum had to make choices based on the best evidence and the advice of historians, curators and experts in the field of human rights.

These controversies should not distract attention from the truly positive impact the museum will have on Winnipeg and Canada.

Thousands of schoolchildren from across Canada will visit the museum every year under agreements negotiated with provincial and territorial education departments.

A poll two years ago showed a majority of Canadians (56 per cent) support the museum, with only 11 per cent opposed. An impressive 15 per cent said they would make a special trip to visit the museum at The Forks.

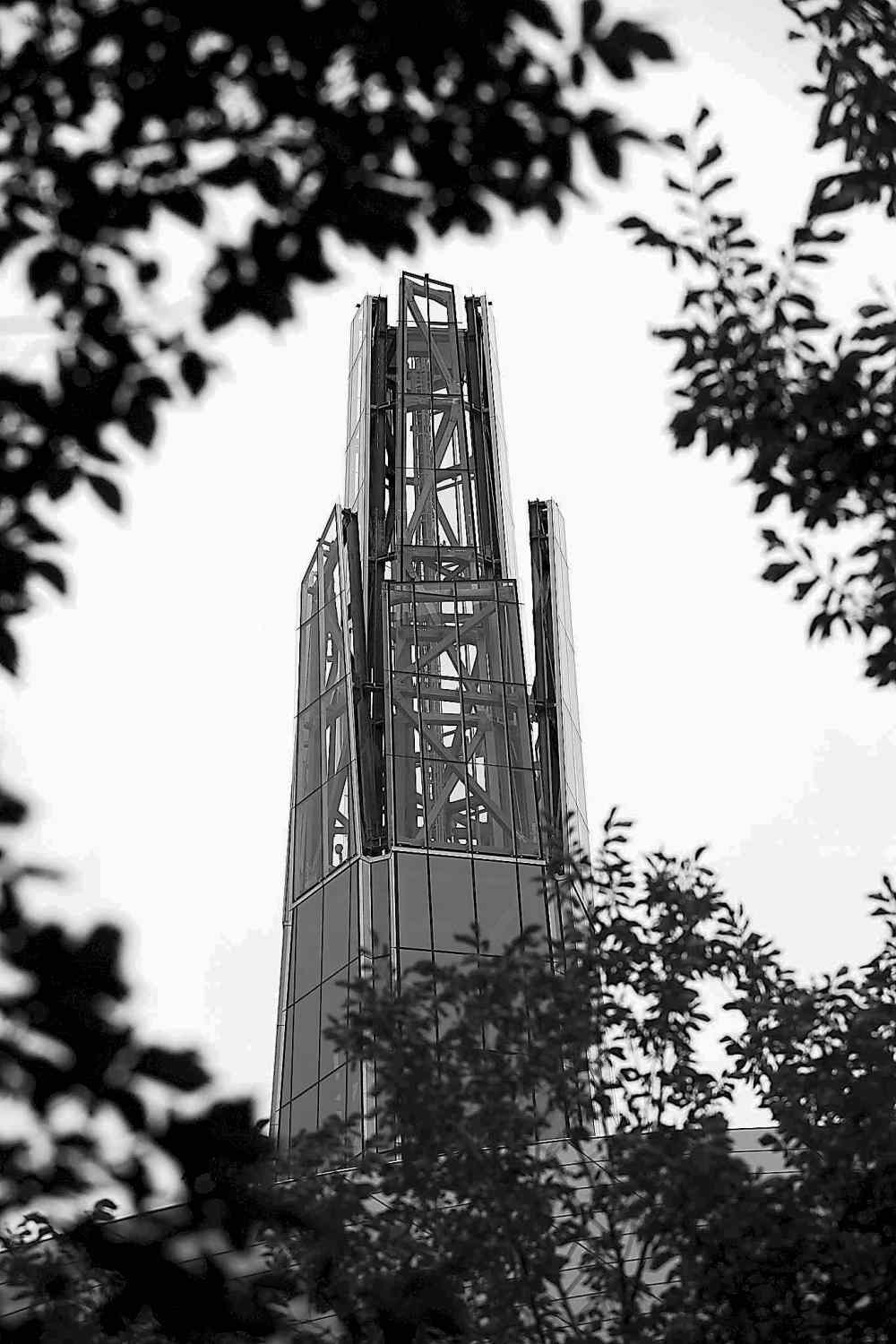

It is not only a great achievement for Winnipeg, where most of the private capital was raised, but also for Canada, whose reputation as a human rights advocate will now be given architectural form and a postcard image for all to see.