One journey ends, another begins

Museum's opening the culminaton of years of blood, sweat and tears

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/09/2014 (4125 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

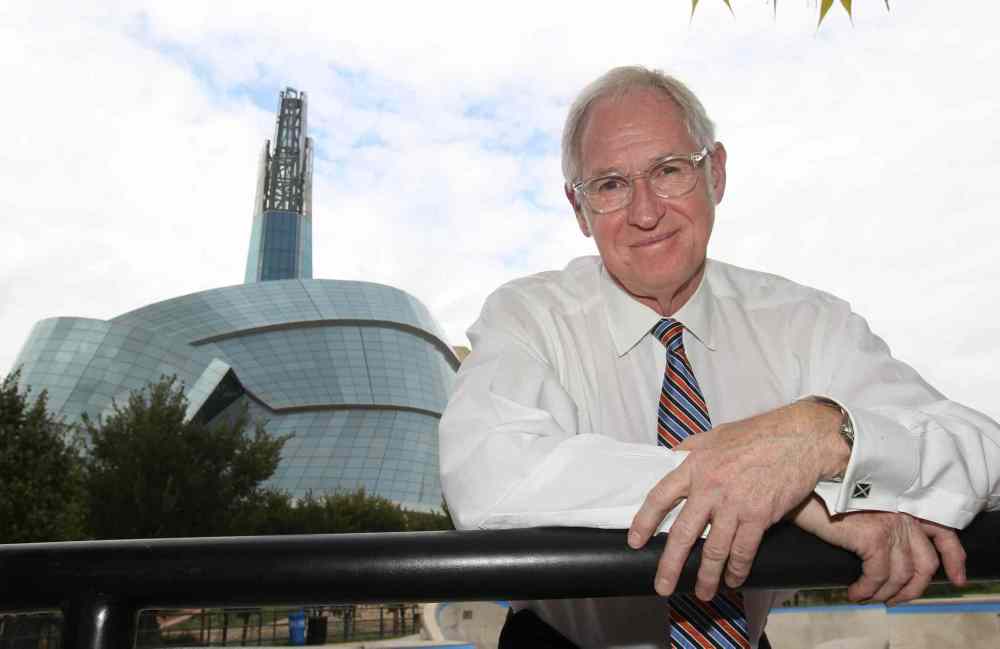

Stuart Murray knows a little about opening acts. And Blood, Sweat and Tears, for that matter.

Back in the day, before he was wearing a pressed suit as Canadian Museum for Human Rights CEO, Murray was hauling equipment and setting up lighting as a roadie for BS&T. He still remembers an outdoor gig in Kansas City where 30,000 fans showed up to see the chart-topping band in the early 1970s.

“The chaos was amazing,” Murray recalled Tuesday. “It was just one of those organic shows that just happened. You couldn’t plan it.”

If there was a fitting motto for the sometimes calamitous, often newsworthy birth of the CMHR, it would be: Blood, Sweat and Tears.

Perhaps that’s why Murray inadvertently used those words when asked to describe preparations for this weekend’s CMHR opening ceremonies, which will include a limited tour for 9,000 people, a music festival and several staged events at The Forks.

“It’s chaotic, it’s crazy,” Murray said. “It’s exactly what I would expect. This show is about to open.”

Ready or not. In fact, the actual opening for the general public won’t be until next week. This weekend’s sneak peek will be limited to four of the museum’s 11 exhibits.

Still, the journey in terms of constructing the body of the museum will officially be over. Which is probably why as Gail Asper looked out from the museum’s sixth-floor Nancy Ruth Board Room, encased in glass, she saw in her mind’s eye a man standing alone in a parking lot outside.

“I keep on having this crazy image,” said Asper, president of the Asper Foundation, the major funding arm of the CMHR. “Imagine a kooky man, 14 years ago, standing in the middle of (the parking lot) late on a summer night. I have an image of him scuffing the ground and saying, ‘Yes, this is where it’s going to be.’ “

Asper was referring to her late father, Izzy, who on the night of July 18, 2000, at around 11 p.m. — she remembers the date and time — called home to announce he’d found the new home of a museum that was at the time just a few-weeks-old concept.

‘I keep on having this crazy image. Imagine a kooky man, 14 years ago, standing in the middle of (the parking lot) late on a summer night. I have an image of him scuffing the ground and saying, “Yes, this is where it’s going to be” ‘

— Gail Asper, on her late father Izzy’s vision for the museum

It would take more than a decade, untold hours of lobbying, $175 million in publicly raised funding, and another $160 million in government funding and an annual operating budget of some $21.7 million to complete the $351-million project.

“You have to remember that my dad was an entrepreneur, and entrepreneurs hallucinate,” Asper said, smiling. “They see things that don’t exist and then they work like hell to make it happen.”

When Israel “Izzy” Asper died suddenly of a heart attack in October 2003, his daughter was certain the project was doomed. Government funding had yet to be approved, and the museum’s major chain-smoking proponent was gone.

“We thought it was pretty much impossible to go forward, even though we wanted to,” Asper conceded. “But within hours of news of my dad’s death… we were just inundated with calls, emails, donations. Everybody said ‘It was Izzy’s vision. Just because he’s gone doesn’t mean the vision has to die.’ “

Instead, the architectural creation of Antoine Predock, with its glass outer dome and cavernous, clean interior, stands to become the most iconic structure erected in Winnipeg since the Manitoba Legislative Building opened in 1920.

Izzy Asper would be proud of his legacy, his daughter said.

“He always said that when you see this museum you’ll know you’re in Canada,” Gail Asper noted, “just like when you see the Eiffel Tower you know you’re in Paris, or see the Sydney Opera House and know you’re in Australia. That’s what he wanted. They’ll want to come to the building. They won’t be able to avoid learning about human rights.”

‘For the first three years we had to keep saying what we are not; we’re not a war museum, we’re not a genocide museum. We’re a museum that’s distinct in the world but uniquely Canadian. It’s a human rights journey’

— CMHR CEO Stuart Murray

Both Asper and Murray agree the opening will at least mark an end to the hypothetical controversies over what the museum will or will not contain.

“Who knows how the world is going to look at us,” Asper said. “But… you have to pick a day that you’re going to just open this thing.”

While the museum will be “flexible” to criticism, Asper added: “There’s been no more consulted, studied museum in the world, I guarantee. We did studies. We did polls. We found out what Canadians wanted to see. How much Canadian? How much past? How much current? We’ve really tried to listen.

“I think there’s been so much input… it’s time to get the thing open. Let’s just start the dialogue.”

The old roadie, meanwhile, can sense when the stage lights are turned up and the curtain is about to rise. And Murray is under no illusions the crowd will always be singing along.

“We’ve had speakers who have come in here and been somewhat controversial,” he said. “We’ve had peaceful protests on our steps already. Those things are going to happen, as they should. I think people will see this as a place — and I hope they do — where they can come and… use it as a centre of dialogue. That’s the beauty of this.

“Instead of having discussions with hard hats and steeled-toed boots on a construction site, we can go to a gallery and stand in front of an exhibit. We can get that conversation going.

“For the first three years we had to keep saying what we are not; we’re not a war museum, we’re not a genocide museum,” Murray concluded. “We’re a museum that’s distinct in the world but uniquely Canadian. It’s a human rights journey.”

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Wednesday, September 17, 2014 6:55 AM CDT: Replaces photo, adds videos