Sanctions ignore pandemic history

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/11/2020 (1931 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

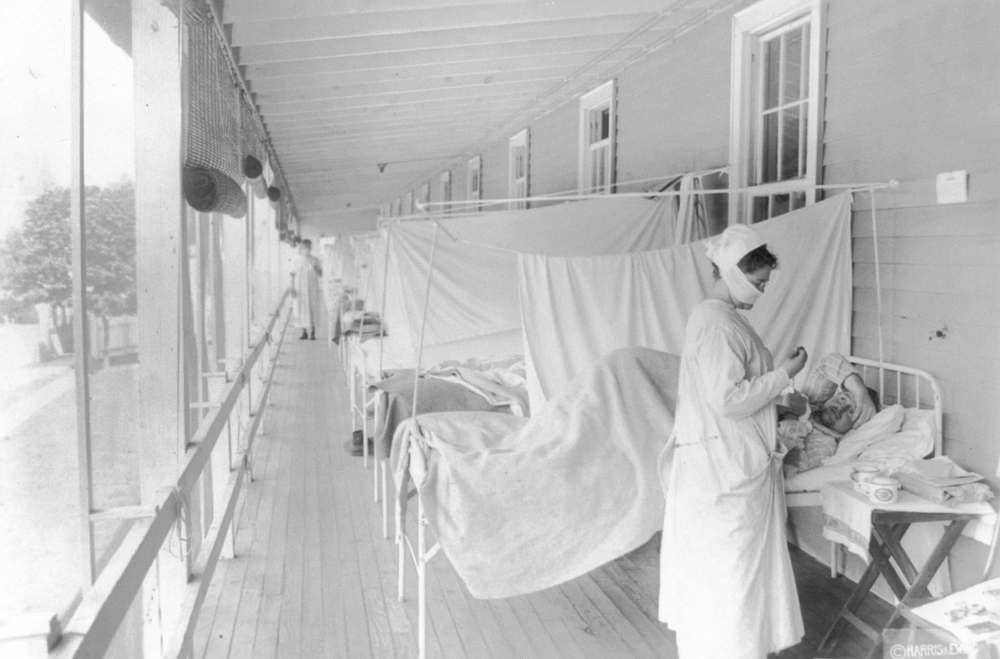

As a historian of epidemics and infectious disease, I have been asked frequently over the past months: “What are the lessons of the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic?” And: “What should we learn from the pandemic of a century ago?”

While history doesn’t actually repeat itself, recently I have been struck by the growing tendency by health officials in Manitoba to ignore hard-won public health knowledge from the past.

After the influenza pandemic of 1918-19, public health practitioners looked back to assess the successes and failures of their response to the outbreak. And they were clear: approaches based on public co-operation and trust were more likely to control the spread of the disease than those based on coercion or punishment.

This is a lesson we are beginning to ignore in Manitoba.

Recently, provincial officials have started to emphasize enforcement and large fines. Police have been emboldened to intervene in public-health policy implementation by ramping up punitive measures.

These developments fly in the face of over 100 years of best practices in public health.

Public-health experts a century ago did not move away from coercion and toward co-operation out of weakness or because they were bleeding hearts. They did it because coercion does not really work during a disease outbreak.

They developed new tools of health education and stronger community relationships because they knew tactics such as placarding homes and policing isolation could serve to undermine broader disease containment efforts.

Why? Most directly, epidemiology and public health measures only work as well as the information on which they are based. Their efforts were less effective if they didn’t know who and where the infected were. So they encouraged sick people to voluntarily report their illness, and then follow the rules of self-isolation.

But as influenza cases escalated at the end of October 1918, public-health officers faced increased pressure to heighten enforcement. The provincial medical officer, Dr. M. Stuart Fraser, adopted an increasingly aggressive public posture, accusing “alien” residents in rural Manitoba of concealing cases of influenza from the authorities. Fraser also insisted that the public should “observe the strict letter of the law” or face “prosecutions to the limit.”

When the pandemic had passed, public-health officers across Canada reflected on the effectiveness of such measures. These experts, who had lived through a harrowing disease outbreak, called not for more enforcement or compulsion, but for a pragmatic recognition of the limits of quarantine, and for the creation of public-health laws that emphasized community co-operation and limited use of coercion and punishment for violations.

By the late 1920s, Saskatchewan’s minister of health argued, “In the protection of the public health from the inroads of preventable and communicable disease, it is necessary that restrictions be placed upon the liberties of the infected individuals; yet, after years and years of the applications of restrictive measures, no indications exist of their efficiency.”

Hundreds of doctors and public-health experts who are on the front lines of this fight recently penned an open letter recommending ways to strengthen anti-COVID-19 measures and increase our preparedness. None of them has argued that the surge in cases and deaths can be blamed on the weakness of an educational approach, the need for higher and a greater number of individual fines, or police enforcement.

The discourse of enforcement projects the illusion of control, in a volatile situation. It is tempting, but is false.

The reasons for COVID-19’s persistence are complex. A multi-faceted approach is key, based on a dual strategy of the fundamentals of good public health (physical distancing, handwashing, wearing masks, staying home when sick) and measures to address social inequities (poverty, racism, poor housing).

Perhaps the greatest risk to ramping up the role of police is that an already fragile public consensus around the painful measures needed to stop the spread of the disease will erode further. This may be especially true among those who experience regulations and enforcement as unfair, arbitrary or simply undoable.

For example, public-health rules introduced at the end of August allowed for immediate fines for those failing to self-isolate, including while awaiting test results. Code Red directives issued on Oct. 30 state that the entire household should isolate if a family member has been tested. Self-isolation orders place a heavy burden on households, without any additional financial supports for those impacted. It is not difficult to imagine why people might now choose not to be tested if symptomatic. How does the threat of a fine help to solve such a problem?

Blaming members of the public, threatening them with large fines and criminalizing ordinary people’s admittedly flawed ways of coping with a pandemic that will likely last for many more months contradicts common sense. Neither is it based in evidence, least of all historical evidence.

Pandemics are inherently social; our solutions must come from a sense of shared responsibility, not individual blame. This was a lesson influenza taught us in 1918-1919 in Manitoba.

Esyllt W. Jones is a professor of history at the University of Manitoba and the author of Influenza 1918: Death, Disease and Struggle in Winnipeg.