Marching into history

Two Winnipeggers reflect on fighting for justice in Selma 50 years ago

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/03/2015 (4001 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Fifty years ago next weekend, Ken Murdoch, a United Church minister born in Port Credit, Ont., was pulled over at night by an Alabama state trooper while he was driving a rental car to Selma, Ala., to fetch water and supplies for people marching along U.S. Route 80 towards the state capitol.

After demanding to see Murdoch’s licence and registration, the trooper shone a flashlight in Murdoch’s eyes and demanded to know, “You one of them?”

Murdoch knew precisely what the officer meant by “them.”

Days earlier, James Reeb, a white minister from Boston who, like Murdoch, was in Selma to lend support to that city’s black community, had been clubbed to death by four members of the Ku Klux Klan.“It wasn’t just an American thing. It was a human rights issue. And it was important to stand up for those things.

-Ken Kuhn

“I was already nervous but then I glanced over towards his patrol car and sitting in the front seat was a guy in civvies. I thought, ‘Uh, oh, these two can do whatever they want to me and nobody’s ever going to know the difference.’”

After what seemed like an eternity, the officer lowered his beacon, tossed Murdoch’s licence back at him and said, “Get outta here.”

“I don’t know whether it was because my licence read ‘Ontario’ and that confused him, or whether it was because the march was finally going forward and there wasn’t anything he could do to stop it, but I wasn’t about to argue.

“I floored it and didn’t look back.”

Murdoch, now retired, has lived in Winnipeg on and off since the late 1960s.

Ken Kuhn is a retired Lutheran pastor who moved to Winnipeg in 1990, to take a position with his church’s national headquarters.

Both men belong to the Chaplains Curling Club, an interdenominational circuit that meets at the Heather Curling Club on Mondays — a day of the week Murdoch jokingly refers to as a “traditional clergy holiday.”

In January, a week or so after the motion picture Selma opened in theatres, Murdoch, Kuhn and a few of their fellow curlers were discussing the film over a bite, after their respective matches. The movie, which was nominated for Best Picture and Best Original Song at last month’s Academy Awards ceremony, tells the story of a series of civil rights marches led by Martin Luther King Jr. that took place in Alabama in 1965 and sparked the passing of the Voting Rights Act, later that year. The act was landmark legislation that prohibited voting based on racial discrimination.

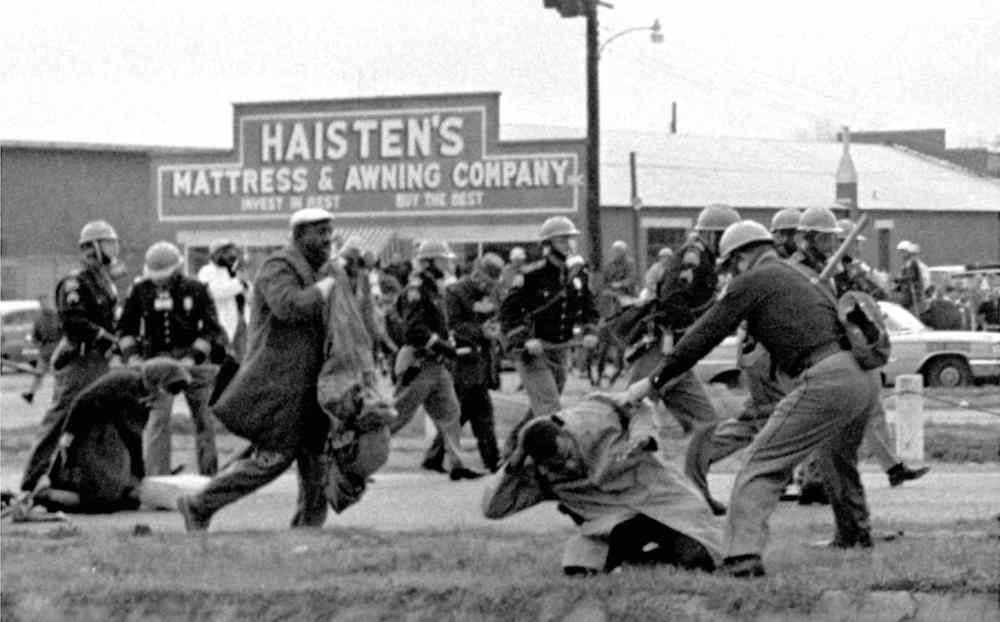

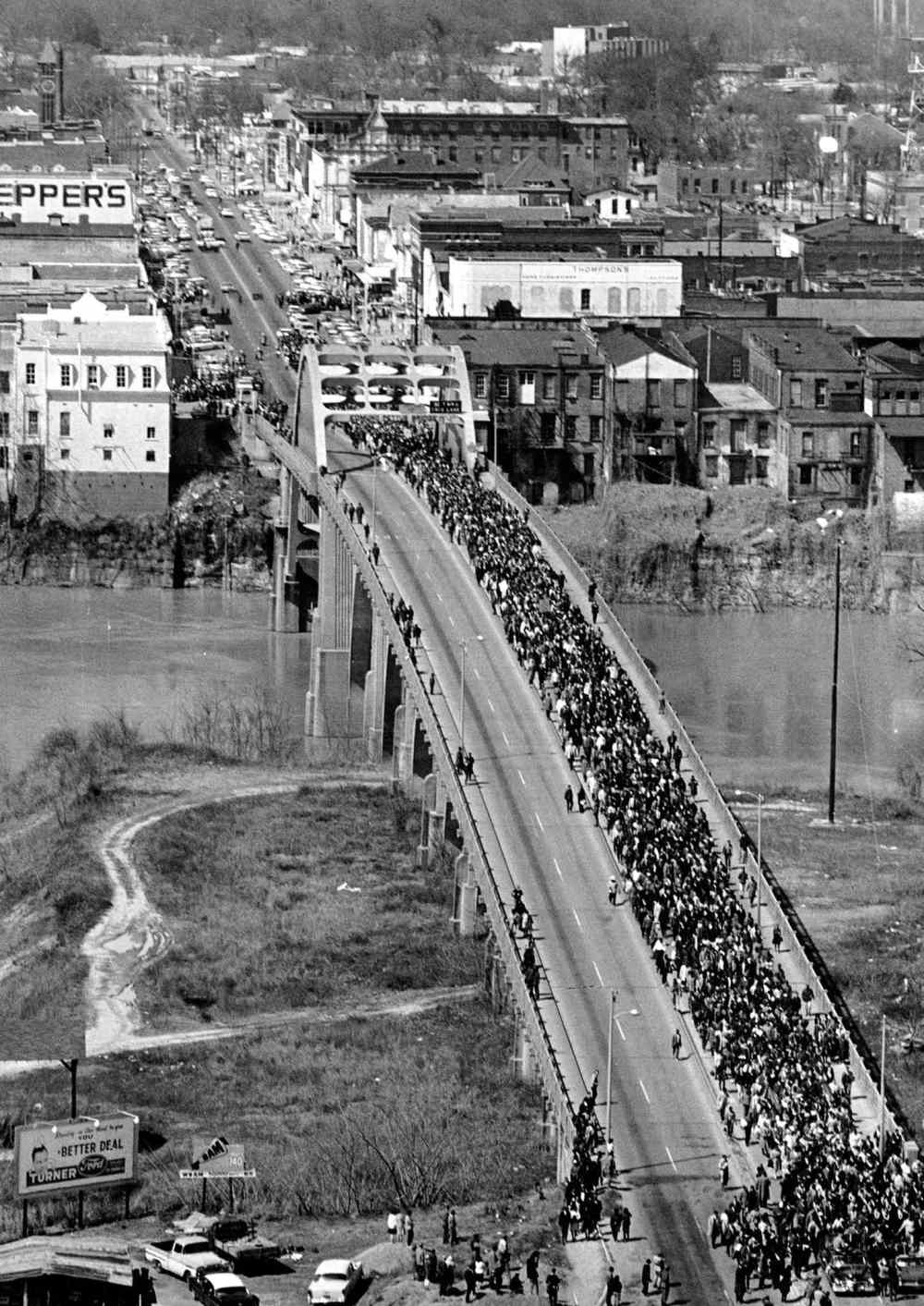

On March 7, 1965 — a day history books refer to as “Bloody Sunday” — King appealed to clergymen from across North America to make their way to Selma to lend support to the cause. King’s plea, which was transmitted live on American television, came a few hours after 600 peaceful protesters were attacked, beaten and tear-gassed by Alabama state troopers at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, which spans the Alabama River in Selma, as they were leaving the Dallas County city for Montgomery, approximately 90 kilometres away.

A person at the table knew Murdoch had been among the handful of Canadians who heeded King’s call, all those years ago, and asked him if what took place on-screen was accurate.

Before Murdoch could answer, Kuhn interjected, saying, “You were there? I was there, too.”

‘It came as quite a surprise when Ken revealed that he had also been involved in the marches,” Kuhn said a couple of weeks later, over coffee at a popular lunch nook in River Heights. “I think he is the first Canadian I’ve ever met who participated.”

“I had heard that somebody else from Winnipeg had been there but until it came up at curling, I had no idea Ken was that other person,” Murdoch added with a chuckle.

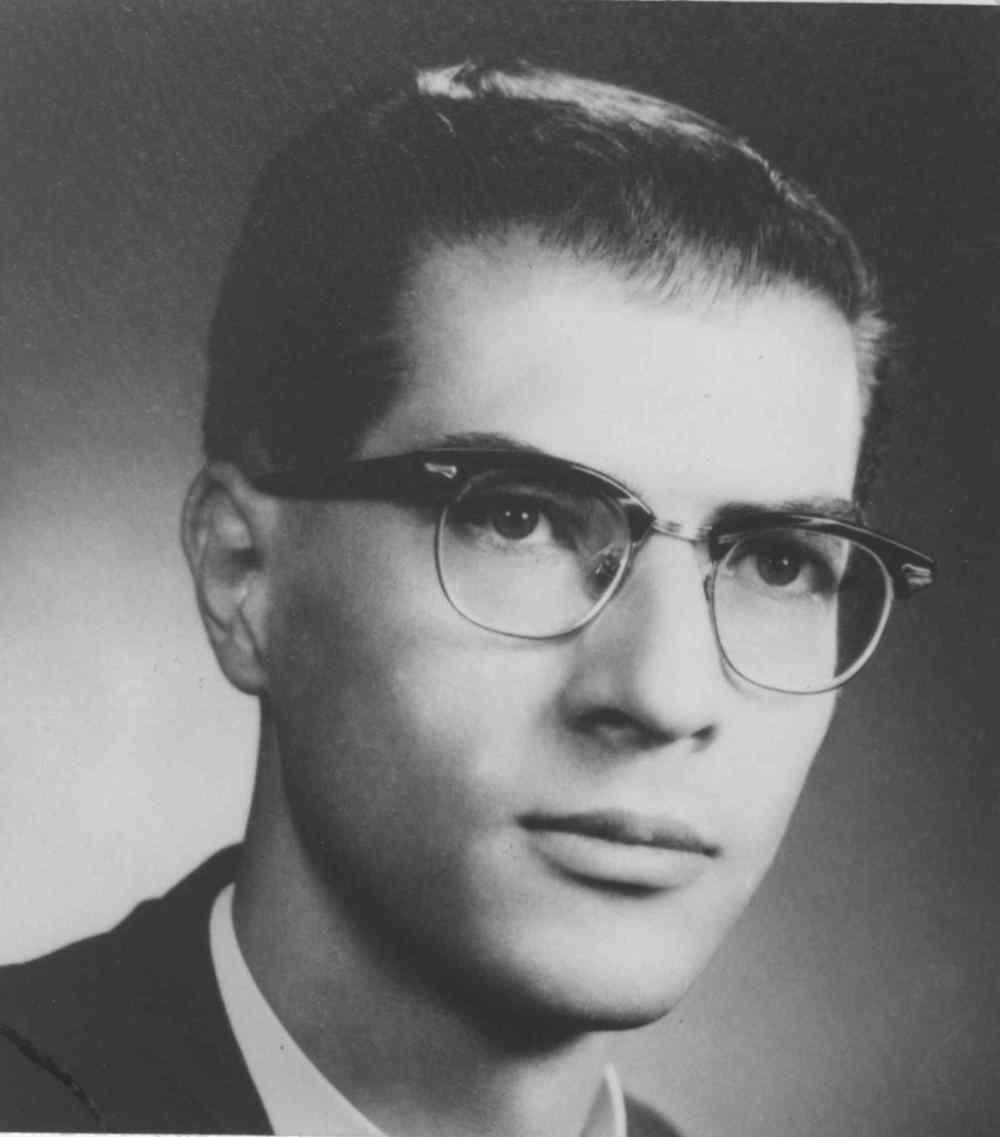

Murdoch and Kuhn, a native of Vancouver, were both living in Chicago in 1965. Murdoch, 27 at the time, was on a nine-month placement at an urban training centre situated in a predominantly black area of the city. Kuhn, then 25, was in his final year of studies at the Lutheran School of Theology.

It’s not surprising their paths didn’t cross in Alabama. Murdoch boarded a southbound train on March 8, the morning after King’s appeal. He arrived in time to walk alongside King on a day that has come to be known as “Turnaround Tuesday” and following that, he worked closely with key strategists such as Andrew Young, helping to co-ordinate the final, five-day march that commenced March 21, 1965.

Kuhn didn’t get to Montgomery until March 24. He was among the thousands of people, including celebrities Harry Belafonte and Sammy Davis Jr., who participated in the final, 10-kilometre leg of the five-day journey. (Before the rally reached City of St. Jude, a Roman Catholic-run organization on the outskirts of Montgomery, there were strict, government-enforced rules regarding how many people could be involved in the march.)

“It was quite exciting to discover that Ken had also been involved,” Kuhn continued. “Our conversation began to fill in details about the march that we had not known about. While we had been acquaintances in the (curling) league before, this common experience has certainly fostered a deeper bond, as our involvement in the Selma-to-Montgomery march for voters’ rights was quite significant for each of us, as an expression of our faith in action.”

Last Saturday, U.S. President Barack Obama, first lady Michelle Obama and tens of thousands of others assembled in Selma for a ceremonial march over the Edmund Pettus Bridge to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of Bloody Sunday.

“Selma is now,” Obama said, in a speech leading up to his appearance in Alabama. “Selma is about the courage of ordinary people doing extraordinary things because they believe they can change the country, that they can shape our nation’s destiny.”

As Canadians, Murdoch and Kuhn weren’t necessarily trying to change the country they were guests in when they travelled to Alabama a half-century ago. But it is true they were two ordinary people who, because of their beliefs, felt it was important to participate in what has since proven to have been an extraordinary event.

Ken Murdoch

In March 1965, Ken Murdoch was working at the Urban Training Centre on the south side of Chicago.

“We had speakers coming in for seminars all the time,” he says. “(Community organizer) Saul Alinsky was one and (civil rights leader) Ralph Abernathy was another. And I’m pretty sure it was through those connections that I and two others, both Americans, made the decision to go to Selma immediately after the call went out.”

The first thing that struck Murdoch about Selma was the difference between the haves and the have-nots. It was as if somebody had taken a pen and divided the town in two, he recalls: black on the right, white on the left.

“There were dirt roads on the right, paved roads on the left, dimmed lights on the right, full street lights to the left. This was all new to me,” says Murdoch, who arrived in Selma March 8, 1965.

The next day, Murdoch found himself on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, along with 2,500 others, including Martin Luther King Jr. Two days earlier, on a day now known as Bloody Sunday, Alabama state troopers had put a violent stop to a similar demonstration and tensions were high, Murdoch says, that an equivalent outcome was in the offing.

“There were butterflies for sure. We had all seen the news reports when state troopers beat up the protesters so my first thought was probably, ‘Oh, s—, what have I gotten myself into?’” says Murdoch, noting he wasn’t wearing anything that day that identified him as a minister.

“The tactic was not to let the police know who you were because King felt the police might not be so quick to attack us if there was a chance the person they were billy-clubbing was a bishop or cardinal or priest.”

Murdoch distinctly remembers reaching the halfway point of the bridge — a juncture that offered an illuminating view of what awaited him and his companions, on the other side of the span.

“It wasn’t just that single line that was depicted in the movie. All down the road, as far as I could see, were trooper cars, parked this way with troopers standing directly in front of them,” Murdoch says, adjusting his glasses. “Obviously I had never experienced anything similar and it was the first time I had the impression of being in a police state.”

Murdoch can’t recall how many minutes passed, but he remembers the march coming to a standstill and everybody around him murmuring to one another, wondering what was supposed to happen next. Finally, King, who was at the front of the throng, broke into a short prayer. Then he called an end to the proceedings and instructed those lined up behind him to return to Selma.

Later that day, Murdoch was summoned to a tiny apartment in Selma, along with a dozen or so other ministers from across the States. (Murdoch assumes it was because of his previous dealings with Abernathy that he was invited to the apartment.)“People started yelling at us, calling us every name in the book. Drivers stopped their cars and rolled down their windows so they could spit on us.”

-Ken Murdoch

The group, quickly labelled the logistics committee, was told the decision had been made to wait for a court order guaranteeing security for marchers, and that was the reason King had put an end to that morning’s protest.

Murdoch and the others were also informed no concrete plans were actually in place for a lengthy trek to Montgomery. And while everyone was waiting for the Justice Department to render its decision, they should spend any free time they had gathering supplies such as water, sleeping bags and toiletries — anything that would prove useful when the march recommenced.

Murdoch lived with a black family during his two weeks in Selma. When he wasn’t working with members of his committee or attending nightly information sessions at Brown Chapel, which served as the meeting place for King’s inner sanctum, he was involved in almost-daily protests at the Selma courthouse. There was a catch: The previous year, a Dallas County Circuit Court judge had issued an injunction forbidding public gatherings of more than three people in Selma to discuss civil rights.

“It was the weirdest experience; we would walk to the courthouse in groups of three, but staggered,” Murdoch says. “On one occasion I was with two black girls, and the moment we passed from the black community into the white community, the white people just froze. People were gaping out their windows, barbershop guys were stopped in their tracks…

“Then, just as quickly, everything unfroze and people started yelling at us, calling us every name in the book. Drivers stopped their cars and rolled down their windows so they could spit on us… You just kind of said to yourself, ‘What the —-? Where am I?’”

Murdoch didn’t deal with King personally while he was in Selma. “You never saw (King). Andrew Young and Ralph Abernathy were his lieutenants, if you will, and that’s who we dealt with, primarily. King was the leader who was always brought in at the last minute, to lead a march or deliver a speech or what have you.”

On March 17, a federal judge ruled in favour of the march. Three days later, President Lyndon Johnson issued an executive order directing 1,000 military, policemen and 2,000 federal troops to Selma to escort the marchers along U.S. Route 80.

Murdoch spent the five days of the march driving back and forth from Selma, bringing those on foot whatever was needed. On March 24, the day before the protest was scheduled to reach the state capitol, somebody on the logistics committee mentioned they would need a stage for King to speak from when he reached Montgomery. It was determined a long, flatbed truck would have to suffice but when a followup question was raised — who here can drive a truck? — Murdoch was the only person who put up his hand.

“I had driven a cement truck for a couple of summers back home, so they arranged for somebody with a pilot’s licence to fly me to Birmingham, to pick up this big semi. So there I was in rush hour in Birmingham, grinding gears, trying my best to get out of town.”

Murdoch spent the last day of the march — March 25 — ferrying people back to Selma, after King’s speech. A separate court order dictated all of the marchers had to leave Montgomery by midnight March 25, so Murdoch and dozens of others spent the next 12 hours driving as many as six or seven people at a time. It wasn’t until Murdoch was back in Chicago that he learned a 39-year-old Detroit woman, who had also been transporting marchers back to Selma, had been fatally shot by segregationists, hours after King’s “how long, not long” speech.

“One of (my) reasons for going to the (Urban Training) centre in Chicago was to experience what it meant to have a ministry to the inner city. In relation to the U.S. situation, that meant experiencing black-versus-white situations, particularly when the white was in the majority,” Murdoch says. “That experience helped me somewhat to understand the South, but not in real, experiential understanding until I was in the southern U.S. at Selma.

“Translating that to the Canadian situation meant my eyes were opened to the plight of aboriginal and other minorities in our (Canadian) inner cities, particularly aboriginals in western cities like Winnipeg. A stark realization of this was my family’s property deed on the banks of the (Port) Credit River near Toronto included a caveat of a 10-foot path ‘for the purposes of the Mississauga Indians to launch their canoes.’ Little did I know at that time about the reality of that ‘requirement.’ ”

Ken Kuhn

Ken Kuhn remembers the events of Bloody Sunday, but sketchily.

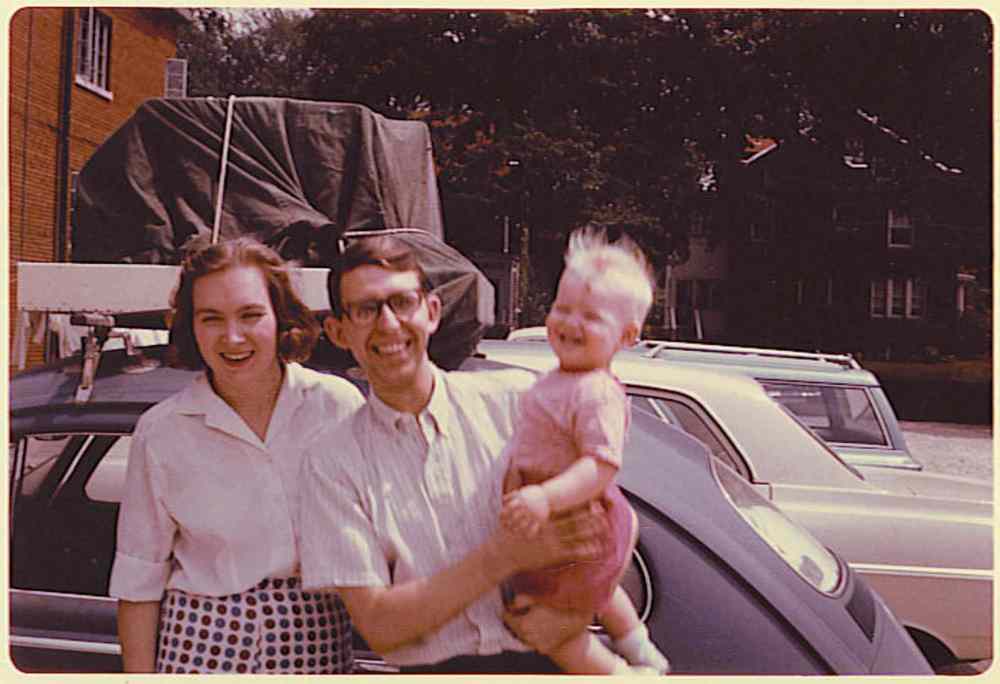

“I was married at the time and we had a child, but we didn’t have a TV set,” he says. “We lived in a two-room, student housing project in Chicago, where I was in my fifth and final year at the Lutheran School of Theology. I subscribed to the newspaper and to Newsweek, so that’s probably where I first learned about the goings-on in Selma.

“I don’t remember the specifics but I remember being quite moved by the brutality of that first march; I certainly remember that.”

On March 22, 15 days after Bloody Sunday and 24 hours after marchers left Selma for Montgomery, one of Kuhn’s fellow classmates knocked on his door to say a group of six students was planning to leave for Alabama the next morning, and did Kuhn want to join them.“We’ve got our Selma here in Winnipeg, too.”

-Ken Kuhn

“I certainly had to think about it; I had a number of hesitancies, I must say,” Kuhn says, taking a sip of his coffee. “One factor was I was married with a one-year-old, and my wife was concerned for my safety. A second hesitancy was that I was Canadian, and this was an American thing. ‘Who am I to be involved in American politics when I’m not a citizen?’ I asked myself. If something happened, I could lose my green card.

“But I came around to say it wasn’t just an American thing — it was a human rights issue. And it was important to stand up for those things that are important.”

Kuhn arrived in Montgomery by train on March 24. From there, he and thousands of others were bused to City of St. Jude, the gathering point for the final leg of the march.

“Apparently there were 25,000 of us in St. Jude and believe me, it felt like 25,000. I was a drop in the ocean, a fly in the ointment, just going with the flow.”

Kuhn recalls it was a comfortable day — warm but not stifling — when they walked the 10 kilometres from St. Jude to the capitol building. He remembers listening to folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary perform in Montgomery (“I was into folk music at the time, along with the Bible,” he chuckles) and he estimates he was about a few hundred metres away from Martin Luther King Jr. when the civil rights leader delivered his speech.

“He spoke for probably half an hour or so, and I remember him using a term that appealed to me. He talked about people of goodwill — people who weren’t just motivated by religious attitudes or nationalistic attitudes, but people of goodwill. I think that was the expression of the deep human rights that is so important.”

Kuhn, who caught a train back to Chicago hours after King spoke, compares what he learned 50 years ago in Selma to problems facing Canadians in 2015.

“We have our own issues in Winnipeg, in Canada, and the issues are different (from Selma’s) but they are similar, especially with the aboriginal population. Now the aboriginal population were original people in Canada whereas the black population in the U.S. were brought in as slaves — so there is a difference — but the outcome, problems with poverty, is the same.

“I think the biggest issue in Canada right now is the fact education on the reserves is terribly underfunded and that is feeding the problem of systemic racism. It feeds poverty, it feeds poor attitudes, it feeds addictions — that bad feeling many aboriginals have about themselves. So yes, we’ve got our Selma here in Winnipeg, too.”

david.sanderson@freepress.mb.ca

Dave Sanderson was born in Regina but please, don’t hold that against him.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.