St. James Cemetery a who’s who of local history

McDermot, Bannatyne, Mulvey, Inkster among famous people laid to rest

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/08/2016 (3370 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

While many of the founding pioneers of Winnipeg are resting eternally at an old cemetery on the banks of the Red River in the city, their sons and daughters are a few kilometres away along the Assiniboine River in St. James Cemetery.

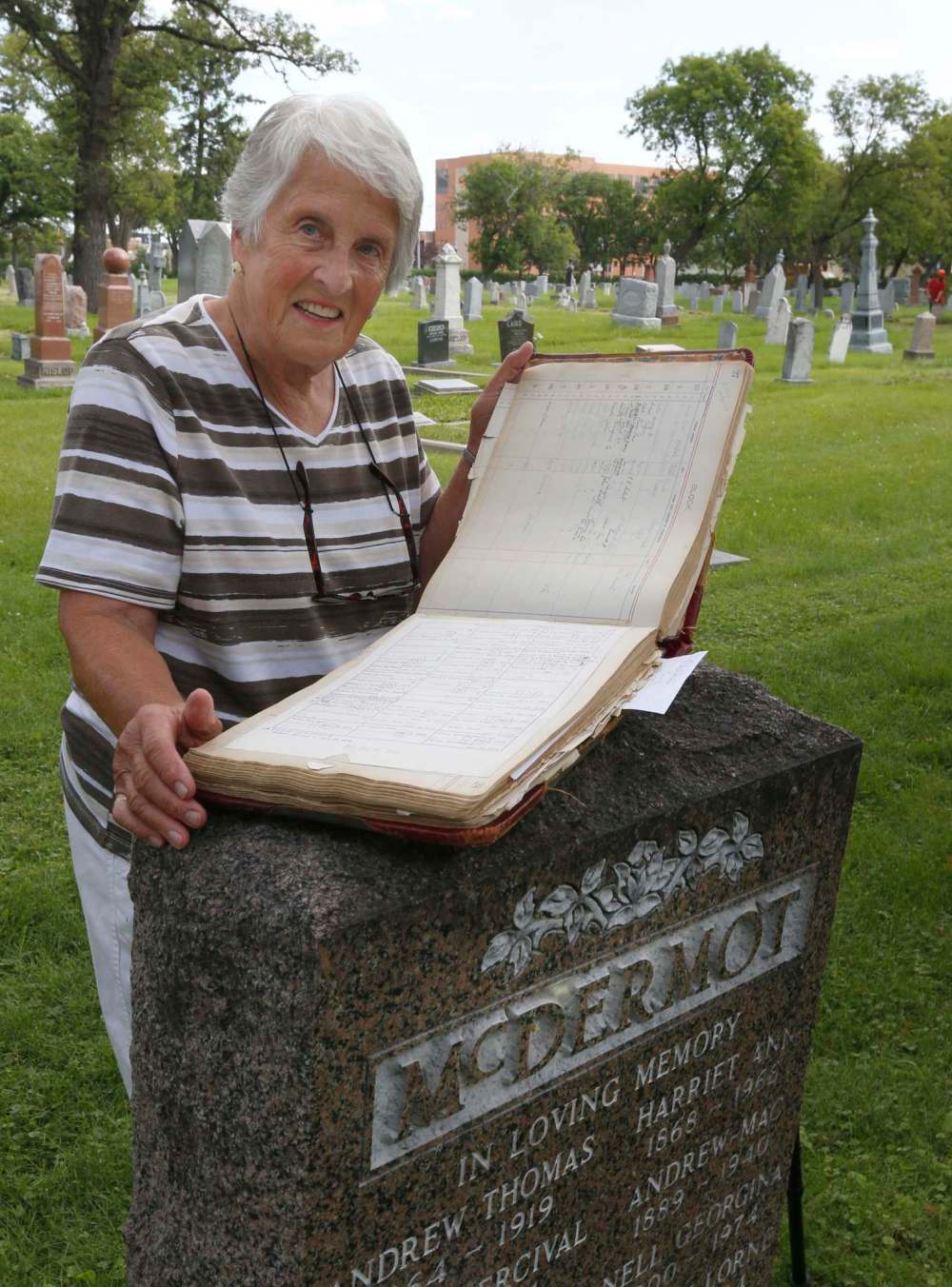

Walking through the park-like setting, just a stone’s throw from the Polo Park mall, and looking at headstones more than a century old, you quickly see many of the same names echoing those in the St. John’s Cemetery, the oldest European cemetery in the province — McDermot, Bannatyne, Mulvey, Omand and Henderson.

Margaret Steele, the manager of the St. James Cemetery, said there’s a reason for the similar names.

“The original pioneers had their land along the Red River,” Steele said.

“But their sons needed land, too, so when they were old enough, they received land along the Assiniboine River. St. John’s was too far for them to go to church and too far for their children to go to school. They asked for a new church.

“So they went to church here, and when they died they were buried here.”

The 14 acres of land on which the cemetery and the church sit, about six kilometres west of where the Assiniboine River meets the Red River, was granted to the Diocese of Rupert’s Land by the Hudson’s Bay Co. in June 1851.

The Church of St. James and cemetery became not only a place to worship and be buried, it also gave its name to the district, then the city, and then the suburb that grew beside it in the decades to come before amalgamating with Winnipeg in Unicity in 1972.

After a re-survey was done of the Red River Settlement in 1875, it was determined the Church of St. James had 284 acres of land between present-day St. James and Empress streets and north to Saskatchewan Avenue, now the site of Polo Park, former sites of the Winnipeg Arena and Winnipeg Stadium and various big-box stores and other buildings.

“Almost 200 acres was sold at $35 an acre — if only they had decided to rent the land out instead of selling it,” Steele said chuckling.

The building of the church was delayed a year after the logs to be used for its construction were swept away by a flood in 1852. The church was completed in 1853.

A tower was built as part of the church, but it was taken down in 1871 when it was found its foundation couldn’t support its weight.

Tongue partially in cheek, the peoples’ warden of the church, Elizabeth Bonnet, hints there may have been another motive due to the events that took place there in 1869 and 1870.

“My conspiracy theory, which I can’t prove, is it was taken down because during the Riel Rebellion they used it as a tower to look for soldiers coming in to attack from Portage la Prairie. Is it a coincidence it was taken down a year later? Hmm.”

The cemetery received its first official internment Dec. 10, 1856, when nine-month-old Jane Isbister was buried there.

Since then, more than 9,200 have followed her. Some of the original families have almost two dozen family members resting together.

Many of the headstones are a who’s who of St. James. They include names that are now used for streets, schools and buildings including Inkster, Bruce, Pinkham, Chapman and Fidler.

But there are also babies — so many babies. There were likely many tears shed in the several pockets reserved in the cemetery for clusters of young children. Small headstones, either flush on the ground or rising up from the grass, mark where the children, either at birth or just a few months or years into their lives, were buried.

“There are hundreds of babies here,” Steele said.

There are also at least two former mayors buried here.

Col. Thomas Scott came twice from Ontario, in command of troops sent to both Red River Rebellions in 1870 and 1871. When Scott — not to be confused with the Thomas Scott who was arrested and later executed after helping attack the Métis who occupied Upper Fort Garry in 1869 — retired from military service in 1874, he decided to stay in Manitoba,

Scott founded the Scott Furniture Company and was elected to serve on Winnipeg’s first city council. His political career rose quickly as by 1877 he was the city’s third mayor, was elected an MLA a year later and voted in as Conservative MP for Selkirk a year after that. He died in Winnipeg in 1915.

Robert Steen was a former MLA who was elected a city councillor. He followed Stephen Juba into the mayor’s chair in 1977 but died of cancer just two years later and is buried in the northwest section of the cemetery.

The cemetery also holds several people who died in tragic accidents that garnered.

Marjorie Wood was just 16 when, with her friend 29-year-old Anna Wilson and another woman, they decided to take a canoe onto Lake Winnipeg June 26, 1926. They were all visiting at the cottage of Wood’s mother at Hillside Beach.

The three, who only had one paddle, tried to steer the canoe against the wind and took the advice of people yelling onshore to sit still in the watercraft as it floated out into the lake.

By the time a boat was found and got to the site, searchers found the canoe right-side up with no one in it. The bodies were found later. Wilson is mentioned on Wood’s tombstone as a friend who drowned with her, but it is not known if she is also buried there.

A tall, ornate marker marks the passing of Archibald McArthur, who died March 27, two days shy of his 29th birthday. He was working as a linesman with what became Manitoba Telecom Services when he touched a high-voltage wire while working near Birds Hill.

Alfred Tilley, along with his wife Grace and two-year-old son, James, were passengers on a stalled CP Rail train bound for Winnipeg on Jan. 25, 1920, when another train slammed into its rear near Corbeil. It took a few days to identify all the victims, but the three, along with 12 others, were killed while several more were injured.

The Free Press said the family was laid “side by side in one large grave” at the cemetery.

Separated by more than a century, but only by a few meters, are two victims of homicides.

John Ingo was shot to death Aug. 16, 1887, across the street from Mulvey School, after a fight between his dog and another man’s. Police quickly tracked down Thomas Newton, a man the Free Press described as “a man of bad reputation”, with a gun still in his hand.

Following a trial the next year, during which Newton testified that he shot Ingo in self defence, he was sentenced to death. That sentence was later changed to life in prison.

Decades later, newly married 23-year-old Matt LeNabat was working in California as a security firm supervisor in 2000, when three former co-workers – two he supervised and who had left the company just days before the slaying – kidnapped and strangled him before leaving his body in his burning car. The three were later convicted and, as his headstone says, the slaying was “over a minimum wage job.”

There are also stones marking the people who built the city or originally owned land which became parks.

Charles Wheeler’s tombstone says “architect of this city” and several of the buildings he designed and were built in the late 1800s are still with us today.

Wheeler was the architect of Holy Trinity Anglican Church across the street from the Millennium Library, the courthouse at Broadway and Kennedy Street, and the Macdonald House which is known today as the Dalnavert Museum,

Outside Winnipeg, Wheeler also designed the former provincial jail in Portage la Prairie, schools in Deloraine and Carman, and the Morden Methodist Church. Wheeler died in 1917 after slipping on ice.

Archibald Wright was born in Scotland and came to Winnipeg after making harnesses for horses in the Confederate army and looking for gold in the North Saskatchewan River. He ended up owning 2,300 acres of land on the south side of the Assiniboine River which later became Assiniboine Park and what is now the Asper Jewish Campus. He died in 1912.

Peter Bruce, and his brother James, owned and farmed the land which was later donated to the city and turned into Bruce Park.

James Armstrong didn’t own land in Winnipeg, but decades later it’s his name on a section of the city that people still know.

Armstrong, a British veteran of the Battle of Waterloo, was entrusted by Joseph Hill, the owner of the point of land just east of what is now the Misericordia Health Centre, to look after the property while he went back to England to serve with the British forces in 1854.

Fast forward a few decades and future mayor Francis Cornish bought the land after Armstrong’s death in 1871. But Hill, who was still very much alive, came back, reestablished he was who he said he was, and was able to get back his property, which he then sold to developers.

The area, now known as Armstrong’s Point, has dozens of homes there as well as the Cornish Library.

Frank Thompson knew Lord Baden-Powell and founded the first Scout troop in St. James in 1915, so that his children could be in Scouts. But, after learning that Baden-Powell had now created The Wolf Cubs for younger children, he founded the first cub pack in Canada in December, 1915, with just three members, including the first cub, his youngest son Ron.

During Thompson’s time as Akela, which is marked on his grave, more than 20,000 boys came through the cub movement and he was honoured with the King’s Jubilee Medal and Baden-Powell himself took the Scout Silver Wolf from his own neck and placed it on Thompson.

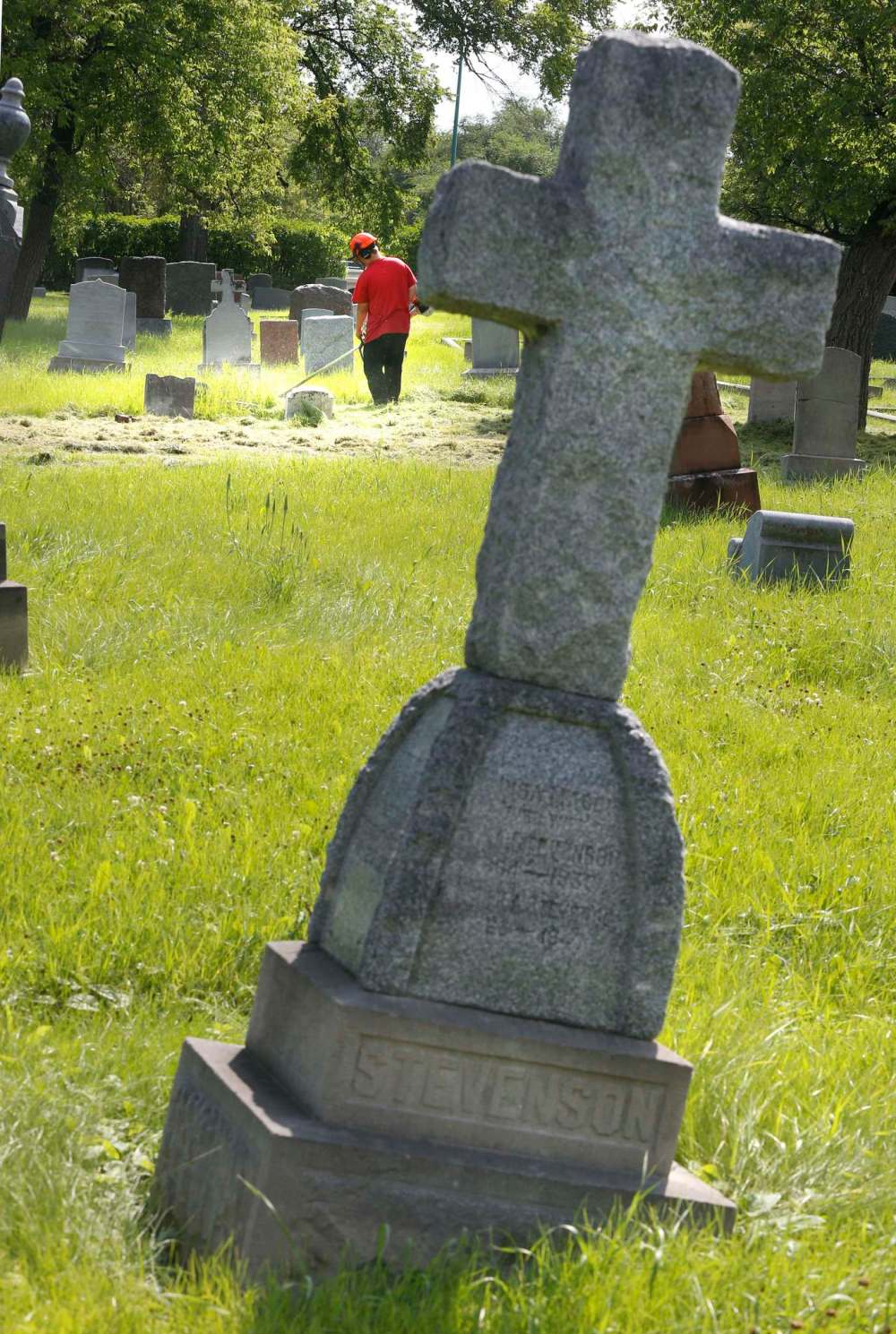

Danny Jolicoeur has been tending to the maintenance of the cemetery for 10 years. Before that, Jolicoeur did the same at St. John’s for two decades.

Most cemeteries today are designed to allow a backhoe to come in to dig a grave. There weren’t any backhoes back in the 1850s so burials were done by hand, allowing some to put brick or concrete around their plot, or to have just a narrow walking path between grave sites.

It means when Jolicoeur is asked to dig a grave for a full burial, he grabs a shovel. It takes him about two days.

“You need a lot of stamina,” he said. “It doesn’t take strength. Six feet down is our limit. St. John’s go seven and eight feet down, but we go six.”

Jolicoeur said he uses an edger if it’s an ash internment and it only takes three hours to dig.

“Roots are a devil,” he said.

“The last thing you want is a grave by an ash tree. There’s just as many roots as there are branches.”

The cemetery was using a single push lawnmower, but recently a benefactor donated two new push lawnmowers and a lawn tractor.

“We cut the grass in one section and you go to the next and when you finish you go back and start all over again,” Jolicoeur said.

Steele emphasizes that although the cemetery has no room to expand, there isn’t a no vacancy sign. There are still spots where a person can have ashes buried.

And Steele said people can always send tax deductible donations to help with the maintenance of the cemetery: St. James Cemetery, c/o 195 Collegiate St., R3J 1T9.

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is a general assignment reporter at the Free Press. He graduated from Western University with a Masters of Journalism in 1985 and worked at the Winnipeg Sun until 1988, when he joined the Free Press. He has served as the Free Press’s city hall and law courts reporter and has won several awards, including a National Newspaper Award. Read more about Kevin.

Every piece of reporting Kevin produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, August 15, 2016 8:09 AM CDT: Adds photos