Alone, afraid and betrayed Family shattered as teacher’s obsession with young girl went unnoticed, unpunished

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

On the surface, David Wray was the perfect teacher.

Charismatic and approachable, he never wasted an opportunity to socialize with parents before the morning bell.

He was creative, too, reaching kids on their level, whether through interactive lessons like classroom Jeopardy or the promise of a sweet reward for a correct answer.

At Sherwood, a kindergarten to Grade 5 school in the River East Transcona division, Wray would hand-pick students for social clubs. Being chosen was a source of pride for the eight- and nine-year-olds in his Grade 3 class.

“Honestly, before everything happened, I was like, ‘How lucky are we that our kids have got a teacher that is so focused on their development,’” the father said in an interview.

That Wray had taken a particular interest in his daughter didn’t raise any red flags. In fact, the parents felt the situation was a dream come true.

“I was able to get some of the inside scoop of what was going on with her each day,” the mother said. “He would send me texts on how she was doing, or he’d send me pictures of her in class. I thought that was cool.”

That dream scenario turned into nightmare.

In multiple interviews, the couple, who asked to remain anonymous to protect their family’s identity, shared in painstaking detail how their faith in a person in a position of trust completely unravelled.

Their daughter, they would discover, was not lucky at all, but a target of her teacher’s intense obsession.

For three years, beginning when she was eight, Wray systematically isolated the young girl in the classroom, grooming her with inappropriate comments and actions, while fellow educators turned a blind eye. Then he slowly invaded her life outside of school, becoming a trusted fixture in the family’s home.

When the psychological abuse finally came to light, the family expected justice. Instead, they were left feeling betrayed.

“Every time we talked about it or tried to get help or make a fuss about it, we were roadblocked.”

“Every time we talked about it or tried to get help or make a fuss about it, we were roadblocked,” the mother said, her voice cracking with emotion.

“After a while, we just didn’t know what to do anymore. We just had to go on with our lives and try to do our best.”

Going to the Winnipeg Police Service proved to be futile.

Despite having what felt like a mountain of evidence — including hundreds of inappropriate text messages that Wray sent their daughter and exhibiting what experts called classic grooming techniques — the family was told that what their child endured fell short of being a crime.

The education system was equally unhelpful.

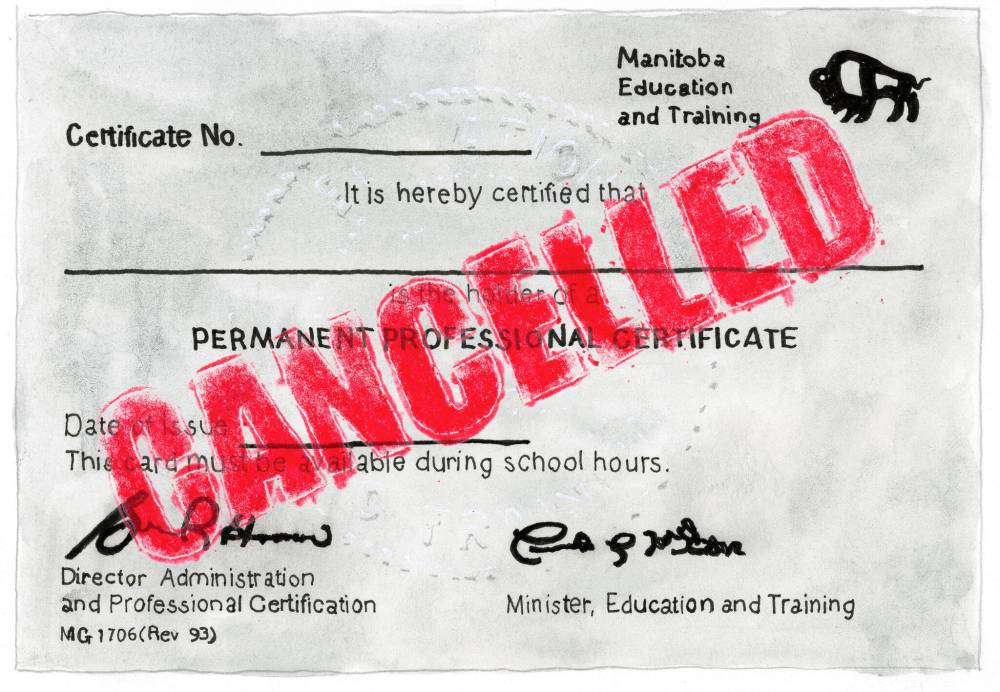

School officials never offered the family support, they said. Wray was allowed to quietly resign, his teaching certificate held in good standing for six more years, until it was finally cancelled in 2023.

“That really pisses me off,” the mother, a former teacher’s assistant, said. “How does that happen?”

“They just bury it,” the father added. “They don’t want anybody to know anything. When somebody does something wrong in the school system, it gets shuffled. It’s like the Catholic Church or something.”

“When somebody does something wrong in the school system, it gets shuffled. It’s like the Catholic Church or something.”

In January 2025, the Manitoba government promised students and schools would be safer with the launch of the province’s online teacher registry and the hiring of an independent commissioner to oversee teacher conduct.

The online portal allows parents to check the status of teachers’ certificates. There are currently 122 teachers with suspended or cancelled licences, dating back to 1990. No details are provided.

As part of an ongoing investigation, the Free Press combed through years of court documents to get a more accurate picture of teacher misconduct in the province.

While the majority of teachers with suspended and cancelled licences were involved in criminal activity, there were exceptions where there was virtually no paper trail.

One of those educators was David Wray, whose name appears only once, in a protection order that expired four years ago.

In delving into his case, the Free Press discovered a child manipulator operating in plain sight and a web of institutional decisions that shielded him, and uncovered how cases of significant teacher misconduct were kept from the public.

The jury is still out on Manitoba’s new teacher oversight mechanisms, as it nears its first anniversary.

What is clear, though, is that the old system was broken, favouring teachers at the expense of children.

And, in this case, altering a young girl’s life forever.

An escalation in misconduct

The first time the eight-year-old noticed something was amiss was halfway through Wray’s first year at Sherwood.

One day during recess, he asked the Grade 3 student to read a letter he had typed on his iPad. She became physically ill when she read the screen.

“I remember throwing up a bit in my mouth,” the now 19-year-old said. “He told me that he was in love with me, that he wanted to sleep with me, that he wanted to marry me and that he hoped I felt the same way.”

At first, she didn’t know what to make of it. Wray had become friends with her parents, especially her mother, who worked at the school.

“He told me that he was in love with me, that he wanted to sleep with me, that he wanted to marry me and that he hoped I felt the same way.”

Wray asked the girl to reply, and she wrote how great it was her parents were so close to her teacher and how special it was to be in his class.

That wasn’t the response he was looking for.

“He had me rewrite it until I said that I loved him, too,” she recalled. “I thought to myself, I don’t know what’s going to happen if I go tell somebody, so I’m just going to sit here and freak out for a second and just do what he tells me to do and then try and leave this room as soon as possible.”

Wray had often kept the student inside for recess. When it was just her, the door was locked.

“But nobody ever came in,” she said. “Nobody ever asked me about it.”

That behaviour escalated when she was in grades 4 and 5, with Wray still her teacher.

She was often selected for clubs he established, on occasion was tasked with leading the class and was allowed to be disruptive without punishment, she said.

Wray would come up with opportunities to see the girl outside of the classroom, too.

He drove her and two friends off-site to music rehearsals; he asked the parents if he could take the girl and her sister to a St. Boniface restaurant so they could learn to order food in French; at one point, he tried to become her coach when she joined a community sports team; and when she became the school patrol captain, Wray became her supervisor and would spend most of the patrol sessions beside the girl.

“If it wasn’t my week of rotation, he didn’t want to supervise. He would say he couldn’t, that he was busy,” she said. “He told me he intentionally created clubs so he could hang out with his favourites and that I was his ultimate favourite.”

“He told me he intentionally created clubs so he could hang out with his favourites and that I was his ultimate favourite.”

As proof, Wray had the girl’s desk positioned directly beside his, facing the rest of the class for grades 4 and 5.

The arrangement reached a breaking point one day when a classmate challenged Wray, the girl said.

“She got sent to the office and it’s the maddest I have ever seen him. He had a full-blown temper tantrum on this child because she had called him out.”

Meanwhile, Wray continued to foster a relationship with the girl’s parents. At times, the mother found herself in the same classroom.

“I never thought anything of it, because me and David were friends,” the mother said. “I just never imagined any of this would be happening, especially in front of me. It’s very embarrassing.”

She trusted him, she said, because their families were similar. He also was married and had two daughters.

The families would hang out socially, visiting Wray’s cabin and going out for dinner. When the Wrays got a puppy, the family was invited over to play with the new pet.

“He then came to me one day and told me he wanted to see me more often,” the girl said. “He said seeing me at school wasn’t enough and that he needed to see me more.”

“He said seeing me at school wasn’t enough and that he needed to see me more.”

Wray convinced the parents that their younger daughter — whose academic achievements he often spoke glowingly of — needed to be challenged beyond the classroom, and he offered to tutor her. It started with French, then art lessons.

By the time the girl was in Grade 5, Wray was at their house two or three times per week, tutoring both their daughters.

As time went on, Wray became more emboldened, the girl said, remembering Wray always wanting to hug her or touch her back, “or have some sort of physical contact with me at all times.”

As her Grade 5 graduation neared, Wray told the girl he planned to apply to teach at Salisbury Morse Place School, where she would attend Grade 6. By then, Wray had taught her a secret language, telling her to make a unique noise every time she left the classroom so that he knew she loved him.

“He was super upset that he wasn’t going to see me all the time, and he told me he couldn’t come to my Grade 5 graduation because he would just be bawling the entire time and it would give it away, and he just couldn’t do that to himself,” she said.

“He told me that I didn’t really love him and that I was lying and that it was going to kill him.”

By now Wray was texting her nightly. Hundreds of messages were exchanged between them over several months, she said.

“His favourite thing to say to me, whenever he would get a moment alone with me, he would tell me that he would love to wake up next to me in the morning,” she said.

“But then he would swear at me and cuss me out for not talking to him enough. He told me that I didn’t really love him and that I was lying and that it was going to kill him.”

The boiling point

Wray did not follow the girl to Salisbury Morse. For the girl, it ultimately allowed for the escape she desperately needed.

She was gaining a better understanding of what a teacher-student relationship should look like and was beginning to question his omnipresence, his behaviour that left her feeling uncomfortable, the frequency of his late-night texting.

But she was afraid to tell her parents and, given Wray’s anger, feared for her family’s safety.

“I just wanted to separate myself from him and just let him be friends with my parents,” she said.

One night, she received a flurry of texts.

Wray was in a panic, claiming his wife had gone through his phone and had read all the messages he’d sent about how much he loved and missed the girl and wanted to be with her.

The girl recalls being home alone with her sister, sitting in her room with her back against the wall, crying, trying to come to grips with what was unfolding.

But what should have been a tipping point barely made waves.

“I had gotten really hopeful, because someone finally knew and it wasn’t my fault,” the girl said. “Then nothing changed.”

“Everything he was doing seemed really out of his way and it was giving me the creeps.”

It was her sister, a year older, who started sounding the alarm.

The sister told her parents, “There is something wrong with this Mr. Wray guy.” For years, she had seen their father check in with her sister every night about a suspected case of appendicitis, which was later determined to be an excuse the girl had used not to attend school.

“Everything he was doing seemed really out of his way and it was giving me the creeps,” the sister said.

“There wasn’t any specific moment where I knew he was doing bad stuff; it just wasn’t normal. It wasn’t what a teacher-student relationship should be.”

More cracks began to appear.

On a drive to Wray’s cottage, the sister begged her dad to turn around, and upon arrival, they argued in the driveway, as she tried to convince him something wasn’t right.

“My dad’s main argument was that they didn’t have many adult friends, and they were excited to have an adult friend,” she said.

“It kind of blinded them to what was going on, and I was telling him that he’s not their friend. He’s (my sister’s) friend.”

The final straw came as the girl was nearing the end of Grade 6.

It was Mother’s Day and Wray asked the girl if he could come to her house because he wanted to learn a song on the piano. But she had had enough; she texted she never wanted to see him again, that she wanted him dead.

Wray then texted the mother and told her he was coming over. When the mom shared the news, her daughter broke down.

“I just started screaming and freaking out. I was shaking and I could barely talk,” she said.

“Mom and Dad pulled me into their room and asked what was going on. I told them, and then it just kind of escalated from there.”

Left in legal limbo

The parents were shattered upon learning their daughter had been traumatized by her teacher — their friend.

“I was in total shock and disbelief. I couldn’t believe what she was telling me,” the mother said.

“I kept thinking: how did I not see it? I started blaming myself. When she told us, it was the most frightening, awful thing that a parent can hear. We’re supposed to be her protectors.”

“Once she told us, everything kind of fell into place,” the father added. “You feel like an idiot, but you see it. It’s like looking backwards at a maze: it’s confusing as hell when you’re going through it, but when you look at it backwards, it’s clear.”

“It’s like looking backwards at a maze: it’s confusing as hell when you’re going through it, but when you look at it backwards, it’s clear.”

What followed was a maelstrom of anger, sadness and despair.

After reading just two text messages on her daughter’s device, the mother said she threw up.

Within an hour, they had called the police, and later handed over their daughter’s iPod Touch, the family iPad and the mother’s laptop.

But while the police talked to the parents — with detectives asking if they wanted them to “scare” Wray with a visit, the mother said — they did not formally interview the daughter.

“The big thing was that I couldn’t give a statement on whether or not he had touched me,” the daughter said, adding she was crying the entire time.

“So, they said they couldn’t do anything because I couldn’t remember if he did or not. It was all about being touched.”

The parents viewed it as a clear case of luring, with hundreds of text messages as evidence.

The police later said no charges would be laid. The father was stunned.

“They said they got it before it became a crime,” he said. “They knew there were messages, they saw them. It was still sleazy and we all understood his intent, but the way they explained it to me at the door was they couldn’t press charges because he hadn’t technically broken a law.

“The grooming, we were told, was not a crime.”

The Criminal Code of Canada says child luring involves using digital communications — such as text messages or the internet — to contact someone under 18 with the specific purpose of setting up a separate, serious sexual crime, such as sexual interference or sexual touching. The law is meant to catch abusers in the grooming stage.

Brandon Trask is a law professor at the University of Manitoba who previously worked as a Crown attorney in the Maritimes with a focus on child sex crimes. Speaking generally, he said the challenge in prosecuting luring lies in proving the abuser’s intent.

“The grooming, we were told, was not a crime.”

Even armed with hundreds of disturbing messages, prosecutors must convince a court the accused’s goal was to facilitate a specific sexual crime.

“The Crown does have to prove that the individual is attempting to facilitate one of these listed crimes,” Trask said.

He would not speak to the details of the Wray matter without having all the information, but he did offer insight into how a police investigation might proceed.

Ideally, he said, police would interview the parents and the victim once a complaint was filed.

Any electronic devices used by the victim to communicate with the perpetrator would be collected as evidence. Having the perpetrator’s device — to align the time stamps of the messages — would strengthen the case, Trask added.

“Unless somebody provided a really clear, coherent, persuasive explanation to investigators, sort of outlining there was no way this constituted luring, I would have been surprised, just generally speaking, to see police not proceed further,” Trask said.

The Free Press requested an interview with Winnipeg police to discuss the specifics of the Wray case and for clarification on the legal factors that determine whether a case meets the criminal threshold of luring, but was denied.

That their daughter was not interviewed by the police still surprises the parents. She was eventually interviewed by Child and Family Services — a session they said included two social workers and “four questions in about 20 minutes.”

“They just took the devices and sent a social worker over to make sure that Mom and Dad weren’t involved in this.”

“They just took the devices and sent a social worker over to make sure that Mom and Dad weren’t involved in this. I’m 12 years old and scared — and they wouldn’t even let me sit with my dog,” the daughter said.

Around the same time, a strikingly similar case was unfolding in Winnipeg.

This case involved a teacher and sports coach — referred to in court documents as M.M. — accused of extensive, inappropriate social media communications with a 12-year-old girl for nearly a year, ending in summer 2017.

Initiated after M.M. coached the girl at a summer camp a year earlier, the messages were highly suggestive of an inappropriate relationship, specifically detailing discussions about “tickle spots” on the body.

Despite the suspicious nature and volume of the messages, police reviewed the evidence and elected to treat the matter “non-criminally,” much like they did in the Wray case.

Following the police’s decision not to lay charges against Wray, another setback followed: the parents’ request for a protection order was denied.

A media report at the time revealed police were incorrectly denying protection order requests when they deemed there was no “imminent threat,” despite a change to legislation a year earlier, which eliminated that aspect of the law.

“He should have been in jail back then. He should be in jail now.”

Had a protection order been granted, police could have arrested Wray when he attempted to contact the girl a year later. When that happened, the courts did grant the family a three-year protection order, valid until May 2021.

Yet it wasn’t the last time their paths crossed.

Wray started to add the girl’s friends on Instagram last year, in hopes of finding her on social media, the family believes. He eventually did and sent her two ‘friend’ requests. Both were denied.

“He should have been in jail back then,” the father said. “He should be in jail now.”

A shattered family

Emotionally exhausted, the parents felt they had run out of options for recourse.

They are all still living with the scars.

“There’s obviously permanent damage,” the girl said. “I had nothing covered for me. I never got therapy through the school. They never offered me anything or even told me where to get help. We had to do it all on our own.”

“I don’t trust anybody anymore — at all, ever,” the father said. “I don’t have a single friend in the world because I don’t trust anyone. My temper, it’s out of control.”

The parents contemplated approaching Sherwood School and division officials, but said it was too difficult emotionally. They also didn’t believe the administrative leadership could give them the justice they sought when the police couldn’t. That was especially painful for the mother.

“I never stepped foot in (the school) again,” she said. “Once this happened, there were no happy memories from there anymore. He erased all of them.”

“Once this happened, there were no happy memories from there anymore. He erased all of them.”

No school official contacted the family about the teacher’s conduct. The only measure of support came from Salisbury’s vice-principal, who, during a chance run-in at a grocery store, said she would keep a watchful eye on the girl and would call the police if she saw Wray near the school, the father said.

The family agreed to tell their story because they don’t want others to experience what happened to them. They also want Wray to be held publicly accountable.

“I want everybody to know his name,” the daughter said. “I really want there to be better education and understanding around what grooming looks like and how it functions.”

The only suggestion that wrongdoing occurred appears on the province’s new online teacher registry. Wray’s name is on the disciplinary outcomes list, his teaching licence cancelled as of January 2023, 15 years into his teaching career.

The Free Press contacted Wray, placing a letter in his mailbox that detailed his actions at Sherwood.

Wray replied via email the next day, saying he wanted to share his account of the events.

He said “the issue” began while he was teaching the girl in Grade 4. He said she was a gifted learner and, over time, “began to want to always be close to me and to want to stay inside at recess with me.”

“It wasn’t until far into this disastrous scenario that I would come to understand what was happening,” Wray wrote.

“I became obsessed with being around her. I wanted to spend every moment with her and when I was away from her, I felt despair. I wanted to talk to her as much as possible. I had constant thoughts of her.”

Wray said his infatuation led to texting. He said these interactions were his way of “replaying conversations we had and thinking of when I would see her again.”

“I became obsessed with being around her. I wanted to spend every moment with her and when I was away from her, I felt despair.”

“Let’s make this perfectly clear: these thoughts were completely non-sexual in nature,” he wrote. “Nothing at any time about this relationship was ever sexual in nature.”

He added: “It was only after the relationship was revealed that I had to figure out why I was so obsessed with her.”

Wray claimed he has suffered from a condition called limerence for most of his life. He said it causes his brain to think he’s in love and that the other person is his soulmate, something he knows now isn’t true.

“What contact with the object of your obsession does is cause your brain to release large amounts of dopamine,” he said. “It has been described as similar to effects of cocaine on an addict.”

Limerence is an intense, involuntary state of obsessive romantic or emotional longing for another person, often referred to as the “limerent object.” It’s characterized by intrusive, fantasy-driven thoughts, acute emotional dependency on the object of affection, and a powerful, almost desperate desire for reciprocation.

Limerence is not recognized as a formal clinical or medical condition in major diagnostic manuals like the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or the International Classification of Diseases.

Indeed, the Free Press spoke to several sex abuse experts, as well as two lawyers with experience prosecuting sex crimes against children. None had heard of the condition, which was popularized by psychologist Dorothy Tennov to distinguish between genuine, mature love and intense, often unhealthy obsession.

Experts argue this defence does not negate the calculated actions of isolation and control that constitute systematic grooming and emotional abuse.

Wray said he wasn’t using limerence as an excuse, adding that he “wouldn’t wish this condition on his worst enemy.” He then shifted his focus to what Child and Family Services had determined about his behaviour following their 2017 investigation.

“I know they accused me of grooming, but that was their impression,” he said. “In my opinion, it was a preconceived bias on their part.”

Wray acknowledged his attempt to contact the student that led to the three-year protection order, noting it was fueled by alcohol, which he said he was using as a survival mechanism.

It wasn’t long after that he said he found a psychologist familiar with limerence, who was able to identify traumas from his childhood that led to the condition.

“Now I understand what has gone on in my mind and the knowledge of it has helped me to find ways to never let anything like this happen again.”

“You may think I’m using this as a cop-out, but I am not,” he said. “What happened was so wrong on so many levels, but now I understand what has gone on in my mind, and the knowledge of it has helped me to find ways to never let anything like this happen again.”

Wray confirmed that the police interviewed him when his behaviour was first reported and again after his attempt to reconnect a year later. He said they told him he wasn’t being charged.

“I acknowledge the damage its effects had on my student, as well as my family,” Wray said. “It’s like it took over my life completely.”

Following the CFS investigation, Wray said the Manitoba Teachers’ Society arranged a meeting with a union representative.

The staff officer handling his case was Arlyn Filewich, now the MTS executive director. Filewich was previously the director of labour relations, the position that oversees all teacher discipline, which, until this year, had been adjudicated behind closed doors.

“It was clear to me that I was done as a teacher,” Wray said. “Instead of facing the school division to explain myself, I agreed to resign my position.”

Wray said at no time was the status of his teaching certificate discussed. It was left in “good standing” until 2023, when then education minister Wayne Ewasko asked him to voluntarily surrender his certificate, which he did.

The Free Press sent Wray a list of follow-up questions regarding his behaviour, but he did not respond.

“Clearly, it damaged me professionally, as this type of situation should,” Wray said. “I live with the scars of this situation daily.”

A wall of silence

The Free Press investigated the Wray case to shed light on how previous systemic failures allowed teacher misconduct and disciplinary actions to remain in the shadows, leaving families and their children oblivious to potential dangers.

Efforts to find answers hit the same wall of silence the girl and her family faced.

Key officials — from the River East Transcona School Division to the provincial government, past and present — shut down conversations.

The Free Press attempted to contact administrators who were at Sherwood and Salisbury Morse Place schools at the time, but the division channeled all responses through superintendent Sandra Herbst.

Herbst, who became superintendent in 2022, refused to disclose details of Wray’s departure, citing confidentiality and privacy legislation. Herbst did confirm a complaint was filed in June 2017, followed by an internal investigation, and that Wray never returned to the classroom. His employment with RETSD ended in 2018.

”Your questions related directly to confidential personnel matters require the disclosure of personal information of third parties,” Herbst wrote. “As a consequence, RETSD is unable to provide that information. We suggest that you contact the former employee, directly, to request the information you are seeking.”

The division wouldn’t disclose why it didn’t interview the victim or her parents for their internal investigation and wouldn’t comment on whether any support was offered to the family. Herbst did confirm the division notified the department of education.

“RETSD remains steadfast in its commitment to ensure that every student learns in a safe and caring environment,” Herbst said.

Colleen Carswell, who has been a school trustee for more than 20 years, including more recently as board chair, refused multiple interview requests but later issued a statement, co-signed by Herbst, that outlined the process involved when disclosure of misconduct involving a teacher and a student is initiated outside of the school system.

The agencies — police, CFS, the Canadian Centre for Child Protection and Manitoba Education and Early Childhood Learning — each have unique but also interrelated obligations, the statement said.

In such cases, typically triggered by CFS or the police, the school division is directed not to interfere to ensure a full external investigation can be completed. The ability of the division to perform an investigation is dependent upon the authorization and information from the outside agencies, the statement said.

“Ultimately, the school division controls the employment relationship with its staff. The WPS deals with criminal matters. CFS deals with child abuse registry matters. MEECL deals with teacher certificate matters.

“In this particular case, we will again reiterate that as soon as the division became aware of concerns, the teacher did not work again for the division.”

“The fact that the division insists that they engaged in a thorough investigation of this situation without contacting the victim or the victim’s parents is absolutely preposterous.”

Cameron Hauseman, an associate professor in the University of Manitoba’s faculty of education, questions the depth of the division’s investigation, considering it didn’t interview the affected parties.

“The fact that the division insists that they engaged in a thorough investigation of this situation without contacting the victim or the victim’s parents is absolutely preposterous,” Hauseman said.

“If anything, they should have been speaking to additional students who have been in this teacher’s class. They should have been speaking to colleagues at the school who might have noticed some of these behaviours.”

Sara Austin, the founder and CEO of Children First Canada, a child advocacy group based in Calgary, said teachers have a legal duty under The Child and Family Services Act to immediately report any information if they reasonably believe a child needs protection.

Austin identified Wray’s actions as a “classic case of grooming.” She said Wray “deliberately fostered a relationship with a child and with their parents and caregivers to build a sense of trust,” isolating the victim to “allow for a misuse of power” and make it nearly impossible for the child to disclose abuse.

“What you’re describing really shows a systemic failure to do what is most essential, which is the protection of our children.”

Austin noted there were obvious red flags for his colleagues and administrators: keeping the child alone in the classroom, holding her back from recess and “isolating their desk from other peers.”

Austin found it “unfathomable how nobody noticed this,” but was especially appalled by the lack of action and support by the division.

“I’m honestly stumped. What you’re describing really shows a systemic failure to do what is most essential, which is the protection of our children,” Austin said.

“Whereas we have systems protecting themselves and their institution ahead of protecting the child, and it’s just wrong.”

Both Manitoba Teachers’ Society president Lillian Klausen and executive director Arlyn Filewich refused interview requests. Klausen issued a prepared statement.

While the MTS affirmed student safety is its “highest priority,” the statement emphasized the union’s legal commitment to ensuring teachers are afforded due process.

“Employment decisions, including hiring, discipline, and dismissal, rest solely with school divisions,” the statement read.

Hauseman said MTS needs to take some accountability. The union has legal authority to terminate a teacher’s union membership for a breach of its professional code — even if it does not result in a criminal charge — but refused to exercise that power, he said.

Allowing Wray to simply resign highlights the union’s priority of protecting his employment rights over using their full disciplinary powers, Hauseman added.

“Like many unions, their No. 1 priority is protecting their members.”

“The lack of action that MTS demonstrated regarding this case really demonstrates that student safety is not their No. 1 priority. Like many unions, their No. 1 priority is protecting their members,” Hauseman said.

“What MTS needs to rationalize and figure out, immediately, is how they deal with those competing tensions so the public can still view them as a trustworthy organization.”

Hauseman also believes Filewich, given her closeness to the case and her current leadership role with MTS, should be required to answer for what happened.

The same can be said for current independent commissioner Bobbi Taillefer, who spent 21 years with the MTS and was the union’s executive director when the complaint about Wray was made to the division.

“If she was aware of what was occurring in this situation, and perhaps many others, and failed to act in a way that put student safety first, she’s not qualified to be in her current position,” Hauseman said.

Taillefer refused a Free Press interview request, stating she wasn’t involved in labour relation cases in her role as executive director.

Ewasko, provincial education minister when Wray’s certificate was cancelled, is now the Progressive Conservative Party’s education critic.

This case, among others, is one of the reasons the then-Tory government pushed for greater oversight of teacher misconduct, he said in an email. The legislation passed unanimously in spring 2023 and was enacted when the NDP formed government later that year.

“This is one of the reasons I began the process of establishing the Teacher’s Registry — to remove dangerous teachers from the classroom,” Ewasko said.

When the Free Press sought information from the education department about how the case was handled, a statement was issued weeks later stating that the laws and regulations under the old system for teacher discipline prevented any meaningful disclosures.

“The department cannot provide further information or comment regarding specific historic teacher conduct files, beyond what is available on the registry of certified teachers and clinicians in accordance with section 8.38 of the Education Administration Act,” a government spokesperson said.

“FIPPA does not allow the department to provide any further information on cases that occurred prior to the establishment of the registry.”

The spokesperson said the new oversight mechanism allows for expanded reporting of misconduct, provides clear statutory investigation powers, increased transparency and better access for the public.

“One of these cases slipping through the cracks is too many.”

Since January, the office has concluded two consent resolution agreements, which resulted in the names of two teachers and their misconduct being made public.

The NDP government, while limited by the same privacy laws that facilitated Wray’s quiet exit, has been more direct in acknowledging institutional failings.

Education Minister Tracy Schmidt said her hands are tied in terms of what she can discuss. She apologized for the restraints of the old laws, recognizing the lack of transparency as a frustrating hurdle in the family’s pursuit of justice.

“One of these cases slipping through the cracks is too many,” Schmidt said. “We are putting the resources in place to make sure that we are closing every gap that might exist in our system. It’s going to take time.”

winnipegfreepress.com/jeffhamilton

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

Jeff Hamilton is a sports and investigative reporter. Jeff joined the Free Press newsroom in April 2015, and has been covering the local sports scene since graduating from Carleton University’s journalism program in 2012. Read more about Jeff.

Every piece of reporting Jeff produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.