Silent no more Sexual abuse survivor is fighting to have predators like his former football coach stopped before they do harm

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/12/2024 (355 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It was a moment Max Jenson knew would come one day.

Because the man who had groomed and sexually abused Jenson for years — beginning when he was a senior at Churchill High School — had predicted his own eventual downfall.

When the day of reckoning arrived, Jenson, dressed in a dark grey suit, sat and watched in a packed courtroom as the hammer of justice finally fell.

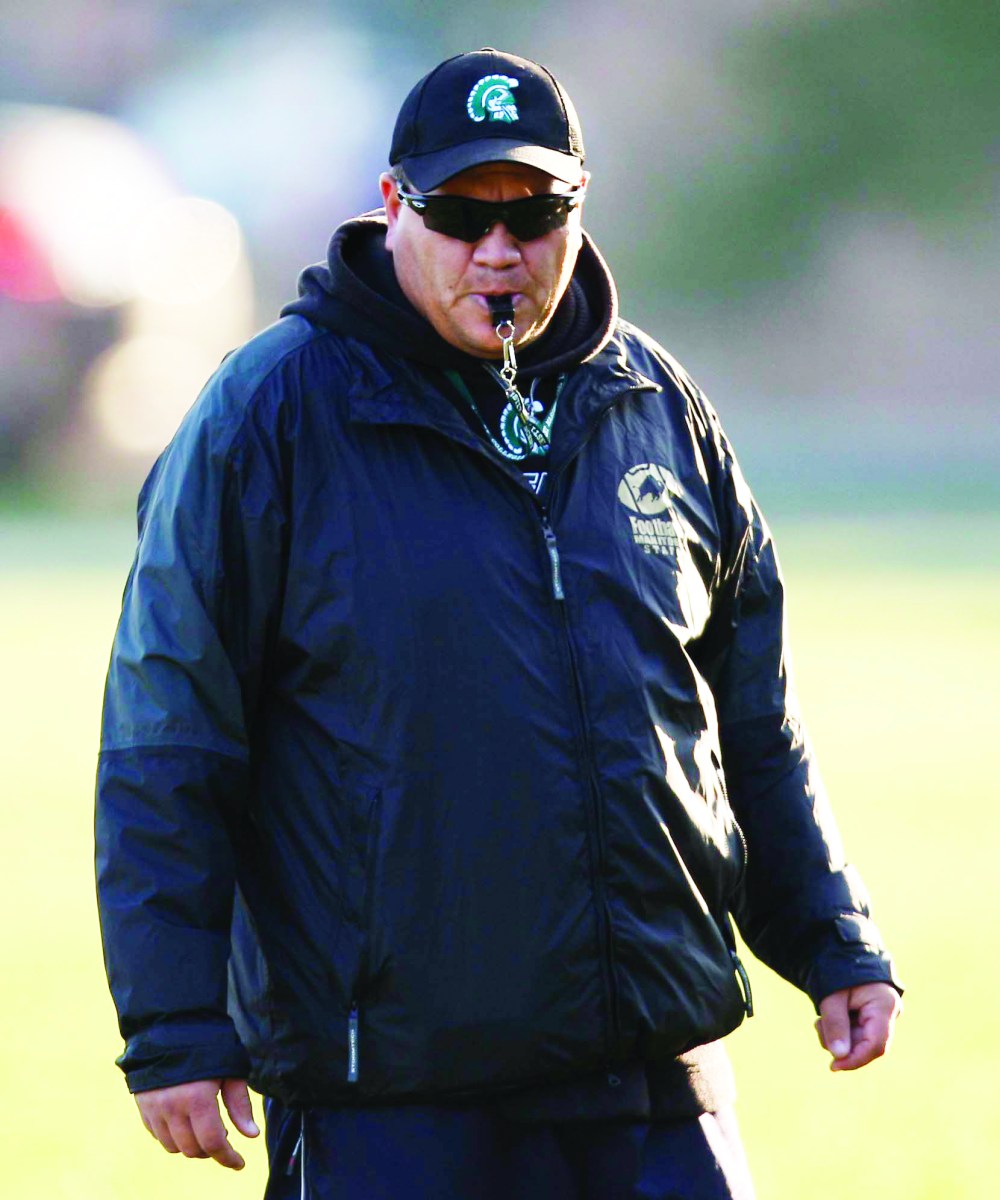

Jenson, now 34, is one of nine victims who came forward against Kelsey McKay, a disgraced former teacher and football coach at Vincent Massey Collegiate and Churchill High School. McKay pleaded guilty in July 2023 to nine counts of sexual assault and two counts of luring his teenaged victims, all of whom he coached.

“He used to tell me about how I and the others would sit down with him, that we’d go for lunch, or maybe it would be in a courtroom, and we’d all tell him how this greatly affected us,” Jenson said in an exclusive interview with the Free Press.

“That’s why I never gave a public statement at the hearing. This was all premeditated by him, so I wasn’t about to give him the gratification or whatever else he wanted out of it.”

All nine victims had their names protected under a publication ban. Jenson made the decision to withdraw his name from the ban so he could go public with his story.

But before that could happen, Jenson needed one final push.

It came in the courtroom in early October as the judge read aloud the horrifying statement of facts and their fallout.

“You see the effects in struggles with personal relationships, suicide thoughts, suicide, addiction issues, post-traumatic stress, anxiety, depression and personal challenges almost too numbing to contemplate,” Judge Ray Wyant said of the victims, before sentencing McKay to 20 years in prison.

“They are all individually and collectively serving life sentences, because even if those effects diminish over time as we all hope, they will never go completely away.”

As the 54-year-old McKay was led out of the courtroom in handcuffs to begin his lengthy sentence, Jenson saw him smile.

That McKay seemed to take some sort of pleasure from the verdict might have triggered Jenson’s trauma under different circumstances. But after hearing the judge articulate the hell he had experienced, a sense of calm came over him.

“It was the first time I actually felt heard; that the people that were associated in this case — the Crown, the police, the judge — that they had heard what I had to say and that what I had to say actually got listened to,” Jenson said.

“I walked into the courtroom in the morning as who I had been living as, and I walked out a different person.”

The way Jenson had been living was fuelled by anger, fear, pain and the feeling of being misunderstood. He likened it to being a child who covers himself with a blanket: although his parents can still see him, he feels invisible.

“That blanket came off during the hearing. It was like the chains were released,” Jenson said. “I could see clearly now, and what I mean by that is I knew what I needed to do. I needed to get our school system changed.”

For the past few months, Jenson has been meeting with child protection advocacy groups and politicians in an attempt to improve a public school system that failed him.

Those groups included the Canadian Centre for Child Protection, Stop Educator Child Exploitation and Toba Centre for Children & Youth.

“They’re shedding light, looking into research and statistics and putting that together and bringing it to the government and other organizations to show that there are issues,” Jenson said.

“They’re advocating for proper measures to help protect victims, help protect children, help the children with coming forward and finding avenues that work.”

He added: “Being a victim myself, not only am I able to seek advice and knowledge from them, but I’m also able to provide them with insight into what happened to me.”

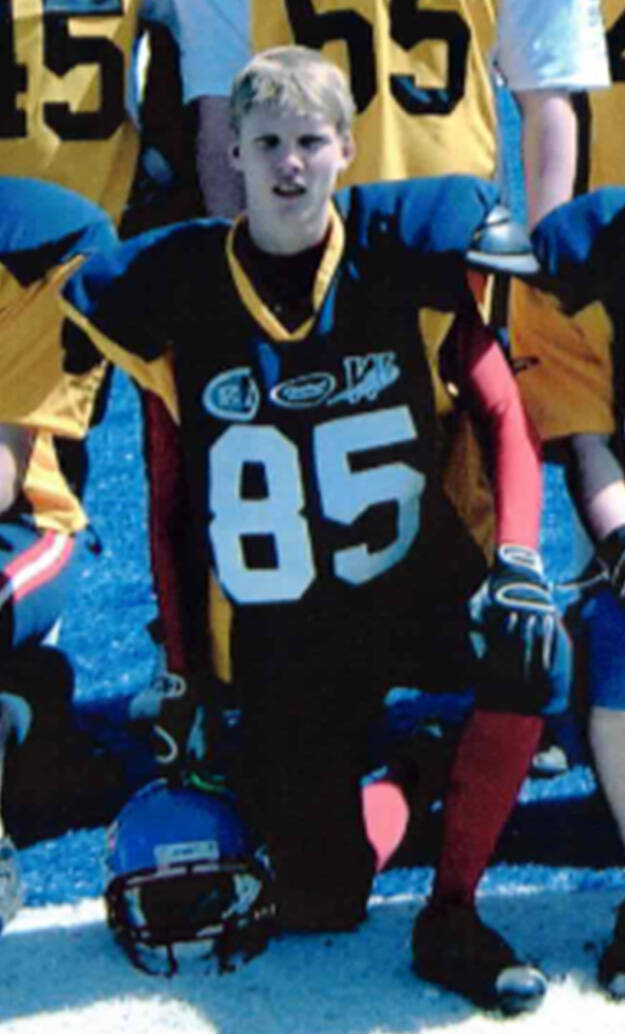

Jenson had no idea what sexual grooming meant when he first met McKay as a scrawny 15-year-old. He was part of a community club football team that shared a field with the McKay-led Churchill Bulldogs.

The other victims have similar stories. All of them and their families were impressed with the interest McKay showed in them.

Like the others, Jenson and his family became sold on the idea of him transferring schools to play for McKay, who not only promised an excellent athletic experience, but talked about developing good habits off the field.

As Jenson’s family foundation began to crumble after his father had a stroke, he would start to see McKay as a parental figure.

McKay became a sounding board for Jenson’s problems, and steadily increased their contact, inviting Jenson to hang out in his office whenever he wanted. By the end of Grade 10 — even before Jenson made the varsity football team — he was routinely joining McKay for Slurpee runs or lunch off school grounds.

“That’s the start of the grooming process,” Jenson said. “All of us were young, most of us had issues at home. McKay knew that and used that to do what he did.”

In the spring before his senior year, McKay started texting Jenson regularly, mostly football chatter. Then it started to get more personal, with McKay asking about Jenson’s dating life and girls he was interested in.

That led to a lunch where McKay initiated a conversation about homosexuality. A short time later, while Jenson and another victim were visiting his house, McKay said he was gay and talked about his sexual encounters with other men.

McKay abused Jenson for the first time not long after that, while they were sitting on a couch as a teammate slept on a nearby chair.

Between June 2008 and November 2011, McKay routinely invited Jenson to his home, and while he didn’t abuse Jenson on every visit, he initiated unwanted sexual contact on at least 12 separate occasions.

“He would cuddle me in his bed, and I would be f—-ing frozen there, hoping it would end,” Jenson said.

“When he massaged me on his couch and would make me sit between his lap, I was never comfortable in any of those moments. Driving home afterwards was never OK. I’d cry on the way home and then I’d cry in my bed.”

Jenson felt severe shame and guilt. He questioned his sexuality. He was confused, because he trusted McKay and didn’t want to let him down.

McKay was physically bigger than his victims and had a stellar reputation in the football community, so Jenson didn’t think anyone would believe him if he told what had happened. McKay had broken down all his defences to the point Jenson was convinced that violence would be his only way out.

“The day when I decided it was going to stop, it was, ‘OK, well, I’m going to have to fight him.’ That’s what I was prepared for,” Jenson said.

Even after the abuse ended and Jenson was years past high school, McKay continued to send sexualized text messages. It wasn’t until early 2022 that communication ceased, just months before Jenson and others came forward to police.

Jenson’s life spiralled after high school, which included a run-in with the law and heavy drinking and smoking. It’s been a long journey since, as he has learned to live with his trauma.

Jenson say he’s grateful for the support of his partner and is relieved that he didn’t develop a drug addiction or worse. One of the other victims was so haunted by the abuse that he died by suicide just months after providing his statement to police.

It’s something Jenson struggles with at times, that others might be hurting more, though he’s not without his own scars.

“He got 20 years, but it pisses me off he could get out after 13 or potentially seven years (on day parole). No amount of therapy is ever going to help. This is something you’re stuck with the rest of your life,” Jenson said.

“Therapy will help you manage it, but you’re stuck with a constant reminder. There’s going to be flashbacks, and all the other stuff that comes with being abused. So, yeah, I absolutely do blame him.

“As I told the police at the end of it, I hope that he sits in a jail cell and rots away, and he just sits there with his thoughts and his thoughts eat away at him. That’s what I want… just like how it’s been done to the rest of us. Because that’s what he sentenced us to when he did this.”

It’s common for sexual assault victims to feel like they have to take action to prevent abuse from happening to others. It’s work that takes an emotional toll.

Former NHLer Sheldon Kennedy told the Free Press as part of an investigation into notorious abuser Graham James that he felt compelled to speak out after news of his abuse went public. The attention eventually overwhelmed Kennedy and he turned to drugs and alcohol.

Jenson knows he doesn’t have the same name recognition as someone like Kennedy, but he’s fiercely determined to ensure that his kids and others have the protections they need to live happy and fulfilled lives — something he was denied.

Although he acknowledges that some measures have been taken since he graduated, he says there are still holes in the system that need to be addressed.

Jenson’s perspective is unique compared to more historical cases because he was abused during the emergence of social media and the use of cellphones in high school classrooms.

“There are many reasons we don’t hear from most victims of abuse, so when they do step up, we have a responsibility to listen and learn,” said Christy Dzikowicz, executive director of Toba Centre for Children & Youth.

“And it’s not just listening because you think it’s cathartic and we need to hear what they have to say because they’ve been hurt. We’ve come a long way in terms of awareness, and we’ve come a long way in terms of what we say we expect from people around children, teachers included, but I still don’t think we’re there in terms of what we actually do to prevent these crimes from happening.”

Dzikowicz noted that when news of predators like McKay and James goes public, what often immediately follows is outrage from society and a renewed commitment from institutions to do better when it comes to protecting children. But just as often, time erodes that anger and the momentum dies.

Part of keeping people on board, Dzikowicz said, involves a balanced approach that doesn’t necessarily mean pointing fingers or trying to assign blame.

“Somehow, we have to remind people without saying you’re all terrible people because you missed it or because you didn’t do anything. That’s not going to move the dial,” she said.

“But we have to listen to guys like Max who are saying there were so many signs, and everyone needs to get more willing to step forward and be vulnerable when you’re not sure, but you just feel like something could be going wrong.”

For Jenson, it’s about establishing more defined rules around teacher conduct as well as enforcing the rules that are already in place.

“When I think of a school, I think of individuals that I was supposed to trust, and now — seeing it as an adult and father and understanding what was acceptable and what’s not acceptable — and you just see these things not being enforced.”

More and more cases of teacher misconduct are coming to light.

According to a study published in November 2022 by the Canadian Centre for Child Protection, 548 students came forward with reports of sexual abuse in Canadian schools between 2017 and 2021.

A total of 252 current and former school personnel from elementary schools to high schools committed or were accused of committing sexual offences.

It was a significant increase from their previous report, in 2018, which found that 1,300 children over two decades, between 1997 and 2017, alleged or were found to have suffered sexual abuse by 714 current or former school employees.

While these reports are among the most comprehensive in the country, they still don’t paint the full picture.

Anne-Marie Robinson is a co-founder of the advocacy group Stop Educator Child Exploitation. She’s also a survivor of child sexual abuse, having been assaulted by her band teacher during a school trip in the 1970s.

Robinson applauds the Canadian Centre for Child Protection for trying to gather statistics on abuse in schools and has been working closely with the organization to improve the system. She said while the stats may seem shocking, they’re just the tip of the iceberg.

“The worst part about the study is that they wrote to every province and asked for the data and most provinces couldn’t put it together,” Robinson said.

“Most provinces didn’t have a system or way of testing, so they kind of cobbled together the data that they did get from the few systems who had some sense of the issue, before ending up going through court documents and various media reports.”

Robinson believes the study is “a gross underestimation” of reality, given the lack of reliable information and the fact that few victims of abuse — particularly sexual — come forward.

“Even with no real system to keep count, there’s still hundreds of kids being abused in our schools,” Robinson said. “Why is there not outrage in the country about that?”

The Manitoba government’s Safe Schools Charter became law in 2004 — the year Jenson started high school and just before McKay’s first season as head coach of Churchill’s football team — making it “a duty of schools to provide students with safe and caring school environments.”

By 2005, all Manitoba schools were required to have a code of conduct and an emergency response plan in place with the support of a Safe School Advisory Committee. Principals are expected to review the code of conduct and emergency response plan by Oct. 31 each year.

“What you get at one school, it’s completely different at another. Why is that?” asked Jenson, who wants to see a universal code of conduct for all Manitoba school divisions.

He wants the legislation to have a greater focus on child safety, including clearer requirements and guidelines when it comes to abuse, the grooming process and acceptable behaviours.

He says the current language is too vague, leaving it open to interpretation, particularly when it comes to cellphones and communication with students via non-school-mandated apps.

“I raise that as a question to parents out there: how many parents know whether or not their kids are texting with their teachers? How many parents know that their kids are talking to their teachers through social media? Because it’s not just McKay.”

Jenson points to occasions where other staff members at Churchill saw McKay taking students out to get Slurpees or for lunch and did nothing. He says some of the football coaches were aware of McKay’s unusually close relationship with certain players, and knew he texted with them regularly and hosted hot tub parties.

JOHN WOODS / FREE PRESS FILES The football field at Churchill High school

All schools in Manitoba encourage teachers not to text students, and the Manitoba Teachers’ Society doubled down on that message during the COVID-19 pandemic as schools moved classes online.

But punishment for violating that guideline varies, with discretion given to individual principals, who often have a close relationship with the accused and aren’t qualified to handle such sensitive claims.

Jenson said better education around grooming would prevent the behaviour from happening; he believes it would have stopped McKay from finding his victims.

He says if schools can teach students about the dangers of abusing drugs and alcohol, why can’t they educate them about the appropriate conduct for teachers and the risks of certain behaviours?

“If you look what happened to us, that was McKay’s playbook,” Jenson said.

“When it comes to the grooming process, the policies put in place to prevent it from happening aren’t even being enforced. They’re being overlooked, which helps normalize that behaviour.”

While grooming often focuses on predator and victim, it also requires the manipulation of a broader environment, including colleagues and parents.

According to the statement of facts in McKay’s sentencing hearing, at least two of his victims came forward to a parent about McKay’s inappropriate communication or touching. Despite their pleas for help, McKay was able to minimize the claims.

McKay befriended families and earned their trust. But there were occasions where parents pushed back, whether it was about him spending too much time with their son or texting at all hours.

But McKay continued the abuse. After he was recruited in 2009 to start the Vincent Massey football program from scratch, his behaviour got even more brazen.

In 2016, three sets of parents complained to the school about McKay. He was acting erratically at practices, verbally abusing players and constantly texting some students to request visits; on at least once occasion, he talked about his sexuality.

They took their complaints first to principal Tony Carvey and then to Pembina Trails assistant superintendent Elaine Egan, who convened a meeting with McKay and a union representative, while notifying superintendent Ted Fransen.

“The majority of parents don’t know where to turn next, they don’t know the proper avenues or channels to go through. So much of what happens in the school system stays in the school system.”– Max Jenson

McKay never denied any of the parents’ allegations. As punishment, he was directed to complete the Respect in Sport course for a third time, as well as the Commit 2 Kids program, which is designed to help child-serving organizations reduce the risk of sexual abuse and create safer environments for children in their care. McKay was also told to review the Staff Interaction with Students divisional policy and to cease all text messaging with students.

But the school and the division never followed up, and while they claimed the police were involved, there’s no evidence of a police report or communications with officers.

McKay continued to text students as if nothing had happened.

“The schools are absolutely protecting themselves, which all institutions try to do in some way,” Robinson said. “You still have to do prevention and education to try to take out a certain percentage of cases at the outset, but once cases are found and there needs to be reporting, then it has to all go outside the organization, because the organizations themselves are in conflict and completely incapable of handling them.

“The system is broken from the front end, right to that back end.”

Jenson has taken his efforts beyond board rooms, speaking with families who have felt stonewalled or dismissed by the school system.

He’s been in contact with one father who went public with his frustrations that the school administration did little to stop the death threats directed at his son. He has spoken to a mother who took her story to the media after her nine-year-old daughter was sent a sexually explicit email by two Grade 4 students, only to find out later that the situation was more heinous than the school had originally revealed.

“The majority of parents don’t know where to turn next, they don’t know the proper avenues or channels to go through. So much of what happens in the school system stays in the school system,” Jenson said.

“What’s very interesting is how fast the system will correct itself when this comes up publicly. It makes me wonder how many other parents give up because they’re exhausted before getting to that point, or do make it to that point but never get that opportunity.”

RUTH BONNEVILLE / FREE PRESS Max Jenson agreed to have his name removed from a publication ban in order to share his experience as a sexual abuse survivor and the efforts he is pursuing to make schools safer for children.

When Robinson, who is a former federal deputy minister, began researching education laws across Canada, she wanted a better understanding of how abuse was still happening and how children were being targeted by teachers.

She discovered it was fairly easy for teachers to get away with abusive behaviour. And she found similar themes in every province, including a lack of accountability from schools and the absence of a truly independent process for reporting abuse and determining punishment.

“I can take you through the pros and cons, but certainly Manitoba had the worst system in the country,” Robinson said.

“I tell people that I know who either have law backgrounds, or people I used to work with in government, that in Manitoba until very recently — though it’s probably still happening until the new process starts — that the teacher’s union themselves were the ones adjudicating these complaints. That’s just absurd from a conflict-of-interest point of view.”

Misconduct cases continue to be obscured from public view. They come before the union — the Manitoba Teachers’ Society — school divisions or the province, depending on the severity; little to no information is made public.

New legislation requiring greater oversight of teachers and more transparency will begin to move forward when the provincial online teacher registry goes public on Jan. 6. Once live, the registry will be limited to the educator’s full name, the date the certificate was issued, along with its class and status, confirmed MTS president Nathan Martindale.

Bill 35 was introduced by the former Conservative government, passing unanimously in spring 2023, and promised much-needed changes to bring Manitoba in line with the law in more advanced provinces.

“That’s my struggle, is that the profession doesn’t represent child safety. It represents a protection, by any means, for adults against the kids.”– Max Jenson

Among those promises is that a commissioner will oversee misconduct and discipline issues; an independent panel will hear misconduct cases; misconduct hearings and their decisions will be made public; and an online registry of teachers will be introduced, including any disciplinary history.

But although the bill received royal assent in May 2023, it continues to be debated behind closed doors by the teacher’s union.

The union, which represents more than 16,000 educators, has called it “open season” on teachers and lobbied for significant changes.

It wants the public registry limited to the teacher’s name and their teaching certificate status, excluding discipline history; a two-year time limit for complaints; and closed hearings.

“As a parent, I tell my children that they’re safe at school and that their teacher has their best interests at hand,” Jenson said. “That’s my struggle, is that the profession doesn’t represent child safety. It represents a protection, by any means, for adults against the kids.”

The changes sought by the union are troubling to abuse and education experts, who question if it’s acting in the best interest of students.

“It’s incredibly disappointing that after all the work and effort that went into Bill 35, that we are not seeing more concrete action at this point,” said Monique St. Germain, general counsel for the Canadian Centre of Child Protection.

“Until Bill 35, there were a number of legitimate concerns that have been raised by several parties about the opaqueness with which teacher disciplinary actions happened. The whole goal is to help ensure that there is transparency and accountability built into the system.”

Martindale said in an interview the MTS is there to ensure children are safe in school, pointing out the union’s code of professional practice states the membership’s first responsibility is to their students.

But when directly pressed on MTS’s main priority — labour rights or child safety — Martindale acknowledged the top priority is safeguarding the welfare of teachers, the status of the teaching profession and the cause of public education in Manitoba.

In the McKay case, that included covering his legal expenses, even after he pleaded guilty, and a union representative accompanying him while in court.

Jenson stresses he had some great experiences in the school system, both as a student and a parent. But he has a hard time reconciling those experiences with the pushback from educators over a law meant to protect children and keep the profession accountable to society.

Bill 35 could have helped stop predators like McKay, he said, which is why he’s determined to fight for change.

“Sitting and talking to people that will hear me out, that’s the easy part. The hard part is this point, showing the downfall, the failures of those that are in a position of power and in a position to protect children not actually following through with their duties,” Jenson said.

“Because if it wasn’t for the system that McKay worked in, that allowed him to do what he did, I wouldn’t be in this place to begin with. If it wasn’t for him taking me off school grounds, for him taking me for lunches and texting, then none of the abuse would have occurred.”

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

Jeff Hamilton is a sports and investigative reporter. Jeff joined the Free Press newsroom in April 2015, and has been covering the local sports scene since graduating from Carleton University’s journalism program in 2012. Read more about Jeff.

Every piece of reporting Jeff produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.