Transformational in form and spirit

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/04/2024 (598 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

WHAT IT IS:

O-ween du muh waun, by Rebecca Belmore and Osvaldo Yero, is an “anti-monument,” as the artists have called it, installed in downtown Winnipeg’s Air Canada Park as part of the 2018 public art project THIS PLACE.

A stack of 30 chairs made from Corten steel, placed upside down on a concrete base, the work is a both a potent expression of refusal and a poetic affirmation of community and connection.

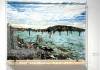

MIKE DEAL / FREE PRESS Made of concrete and weathering steel, O-ween du muh waun was created by artists Rebecca Belmore and Osvaldo Yero in 2018 and is situated in Air Canada Park at 345 Portage Ave.

WHAT IT’S ABOUT:

The tall metal tower is made from the repeated forms of standardized school chairs. The work’s title, a Salteaux term meaning “we were told,” references the traumatic history of the residential school system. By upending the chairs, Belmore, a multidisciplinary Anishinaabe artist from Lac Seul First Nation, and the Cuban-born Yero are symbolically overturning the legacy of colonial education and forced assimilation.

The works in THIS PLACE were chosen and created in consultation with Indigenous artists, Elders, curators and scholars. Taken together, they address what it means to be here on Treaty 1 territory and the homeland of the Métis Nation.

In particular, these pieces reflect on relationships among people, place and history. Within this framework, Michif scholar Cathy Mattes, writing in response to the THIS PLACE project, recognizes O-ween du muh waun as a painful indictment of residential schools but sees more hopeful dimensions, as well. As Mattes suggests, the piece could also reference Indigenous gatherings in community halls, friendship centres, church basements and city parks, where chairs are spread out into circles, for sharing and planning, meetings and celebrations.

This sense of resilience is expressed in the work’s material. Belmore and Yero, who both lived in downtown Winnipeg for a time, are working with Corten steel, often called weathering steel. This material can be seen in construction projects around Manitoba, partly because it holds up so well to the extremes of our weather. Over time, the steel develops an oxide coating that protects the metal from corrosion and keeps it from rusting through. It’s even self-regenerating: When gouged or cut, the surface of weathering steel can repair itself.

Belmore and Yero purposely designed their work to change over time, with the chairs becoming deeper and more complex in texture and colour. As well, since the creation of O-ween du muh waun, the rich rust hue of the metal stack has been gradually seeping into the concrete of the base. It’s a kind of deliberate imperfection that makes sense in a public artwork that seeks to be humanizing rather than imposing.

On a recent day, there was some graffiti on the base, including a message to a child signed, poignantly, “Love You Always, Dad.” On a standard historical monument, this would be deemed vandalism, but with this work, and in the context of the park and its community-based approach to public art, it feels more like another part of the work’s ongoing changes.

WHY IT MATTERS:

Until recently, much of our public art involved large, daunting monuments and statues used to memorialize the famous figures of Canada’s official history.

O-ween du muh waun is a different kind of memorialization. The weathering steel in this work may be tough, but it’s not static or fixed. Transforming in the face of weather and time, it reminds Manitobans that responses to our past are not carved in stone (so to speak) but are part of an ongoing process of recognition and reconciliation.

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.