Gimme shelters Targeted by vandals, claimed by homeless, needed by weather-buffetted transit riders

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/12/2023 (710 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

On a blustery Thursday morning, a lone commuter is bundled up in a work jacket, shielding himself from the elements in a bus shelter at the edge of suburbia.

The Winnipeg Transit shelter, with the panes of glass on each end long since smashed, doesn’t offer much in the way of wind protection, at least when it blows from the east or west.

In Transit

A special series examining the state of Winnipeg’s public transportation system

Minutes later, Mike Pakashvili, a 36-year-old factory worker, gets off one bus to wait for the No. 26. He immigrated to Winnipeg from Georgia with his wife and young son in 2022. He arrives at the Portage and Tylehurst Street bus shack every day around 6:15 a.m.

“It’s no good — it’s always dirty,” he says of shelters like this one, gesturing toward the litter on the ground and the opaque film on its remaining windows.

He, like other Winnipeg Transit users along with the general public, is well aware of the structures’ unofficial dual purpose: to shelter riders, yes, but also to offer respite from the cold for the homeless or those with nowhere to go.

“When it’s too cold, somebody is sleeping, or using drugs — I don’t know — and I stay outside,” Pakashvili says, adding that it’s a particular concern when he’s with his wife and young child.

“When it’s too cold, somebody is sleeping, or using drugs — I don’t know — and I stay outside.”–Mike Pakashvili

Pakashvili does not mind sharing the shacks with the homeless population, he says, but when people use the structures to inject illicit drugs, he takes exception.

“I don’t want my son to see everything, so I stay outside in the cold,” he says.

It’s a tension that Winnipeggers feel most acutely in the winter, when everyone is trying to stay warm.

The question is: Who is the bus shelter supposed to serve?

Transit user Britt Bauer, who answered the Free Press’s call for feedback on the state of transit in Winnipeg, says the shelters — and fixing shelters — is needed for everyone:

JOHN WOODS / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS This year there have been around 1,500 reports to 311 about people sleeping in shelters.

“The bus shelters need to be warmer and have unbreakable glass on them — especially if buses are allowed to be over 20 minutes late or disappear from the schedule altogether,” Bauer wrote.

“People sleeping in the shelters is something that the city has to deal with by providing them with shelter, recovery programs, safe consumption sites, and compassion. In fact, I believe a lot of issues with transit, such as people’s comfort while riding on the bus (and even pre-conceived notions of the buses being unsafe) will be improved when the city starts to deal with housing, addiction, and mental health provision.”

The mayor’s answer is a clear echo: “Transit shelters need to be for transit users.”

Scott Gillingham says the status quo isn’t working for anyone, calling this tension a “frustration” for him as well. They can’t — and shouldn’t — serve as spaces for both transit users and those who need shelter, he says, and accepting things the way they are does a disservice to those who are homeless.

“By allowing them to stay in a bus shelter, we’re not helping them,” Gillingham says. “For a matter of dignity and providing the supports they need, we need to get them out of the bus shelter and into housing, or even a temporary shelter with the services that they require.”

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS ‘Transit shelters need to be for transit users’ says Mayor Scott Gillingham.

Gillingham says the city is putting more funds toward safe spaces, where people can go for immediate shelter and support. In the 2023 budget, city council approved $1 million to expand 24/7 safe space partnerships and help with new extreme weather initiatives. In November, the city announced it was spending $200,000 of that money on expanding pop-up shelter capacity at Siloam Mission, with End Homelessness Winnipeg contributing $65,000.

The city did not make anyone from Winnipeg Transit available for an interview. In emails, spokespeople said the public can help by calling the city’s 311 line if they notice someone sleeping in a shelter. When a call comes in, Winnipeg Transit may be dispatched to do a wellness check or contact an outreach organization.

If it is an emergency, the public should call 911.

However, Kate Sjoberg, director of community initiatives at Main Street Project, says it’s concerning when people are forcibly removed from shelters by authorities.

“There has been a lot of recent unfortunate action to remove people from bus shelters,” Sjoberg says.

She also worries about stigma; “moving people out of bus shelters” has become a government talking point.

“Sometimes, hearing this type of messaging from the top can embolden people to treat the folks in question as if they don’t belong there or are making life harder for others,” she says.

“Sometimes, hearing this type of messaging from the top can embolden people to treat the folks in question as if they don’t belong there or are making life harder for others.”–Kate Sjoberg, Main Street Project

Regardless, community outreach plays a key role in keeping people sleeping in shelters safe.

“We love to just go check in with folks,” Sjoberg says.

Sjoberg echoes what the city email message: if a member of the public sees someone sleeping in a shelter in a non-emergency situation, she encourages them to call 311 or the province’s 211 line, which connects Manitobans with health and social services — or call Main Street Project directly at 204-232-5217. From there, her team can dispatch an outreach van that will swing by and see if there’s anything they can do to help.

Main Street Project works to form ongoing “person-centred” relationships with vulunerable Winnipeggers, Sjoberg says. This can mean anything from offering someone a sandwich to taking them to an overnight shelter. They meet people where they’re at.

JOHN WOODS / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS According to the city, there were 294 incidents of smashed glass in the first 10 months of 2023.

Sjoberg sometimes gets asked: why do people sleep in bus shelters in the first place?

“Well, it’s winter in Winnipeg. It’s really f——-g cold,” she says.

Sjoberg adds that sometimes people choose the shelters because they’re in a public place. People may feel safer there than hidden away from sight, she said.

There’s also the reality that housing — and transit — have historically been underfunded, she says (noting that those who sleep in bus shelters may also use transit — the two groups are not mutually exclusive). Main Street Project uses a “housing-first” approach: Once they are sheltered and safe, they can then better tackle other challenges in life.

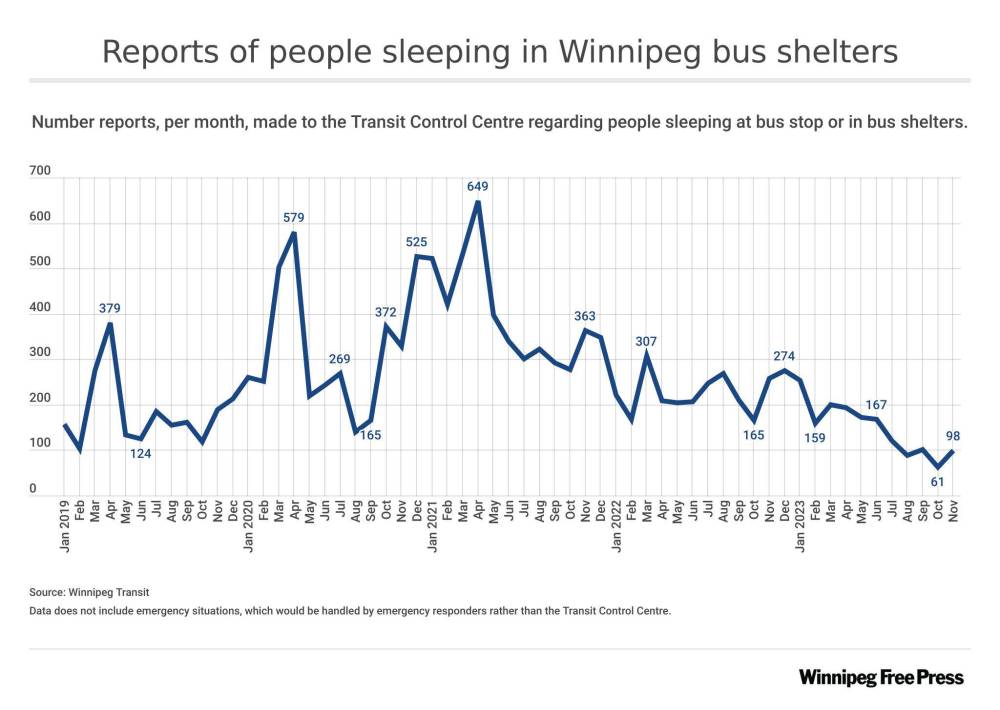

According to city statistics, the number of calls to 311 reporting people sleeping in shelters dropped significantly after a pandemic spike.

For 2020 and 2021, there were between 3,800 and 4,800 reports to 311 about people sleeping in shelters. In 2022, that number dropped to 1,100, though it’s up slightly to around 1,500 in 2023.

But numbers aside, these situations can still leave people vulnerable.

During a bitterly cold stretch in December 2022, St. Boniface Street Links outreach workers found 27-year-old Kayla Rae unresponsive under blankets in a heated bus shelter at Goulet Street and Tache Avenue. The workers administered naloxone, which reverses an opioid overdose, but she later died. Another person was found dead in a bus shelter in April. At other times this year, bystanders and police helped revive people experiencing overdoses in bus shelters by administering naloxone.

Winnipeg’s harm reduction community has long been calling for more services to help those who use drugs in the city.

Another less-urgent, but still pressing matter for the city — one that the early morning commuters noticed most acutely when the wind picks up — smashed shelters.

According to the city, there were 294 incidents of smashed glass in the first 10 months of 2023, 361 in 2022 and 267 in 2021. As of last month, nearly 15 per cent of the city’s 880 bus shelters — 115 — were still in need of glass replacement. Sometimes, the same shelter is targetted multiple times.

Brandon Logan, a spokesperson with Winnipeg Transit, said the city plans to launch a pilot project using polycarbonate-style glass, also known as shatterproof glass, in bus shelters. This is expected to cost two-and-a-half to four times more than regular safety glass but the city would not say how much the regular glass costs. The Canadian Press reported in 2022 that the city spent nearly $700,000 repairing vandalized Winnipeg bus shelters over a 15-month period.

If the trial is successful, the next step would be to focus on shelters “where vandalism is most prevalent and then replace on an incident-by-incident basis.”

– With files from Joyanne Pursaga

katrina.clarke@freepress.mb.ca

erik.pindera@freepress.mb.ca

Erik Pindera is a reporter for the Free Press, mostly focusing on crime and justice.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, January 1, 2024 5:01 PM CST: Adds web headline