Destroying democracy, one deceitful post at a time Increasingly sophisticated deepfake AI-generated internet political ads threaten to unravel Canada’s social order, experts warn, pointing to the successful war on truth Donald Trump is waging south of the border

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/04/2025 (236 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

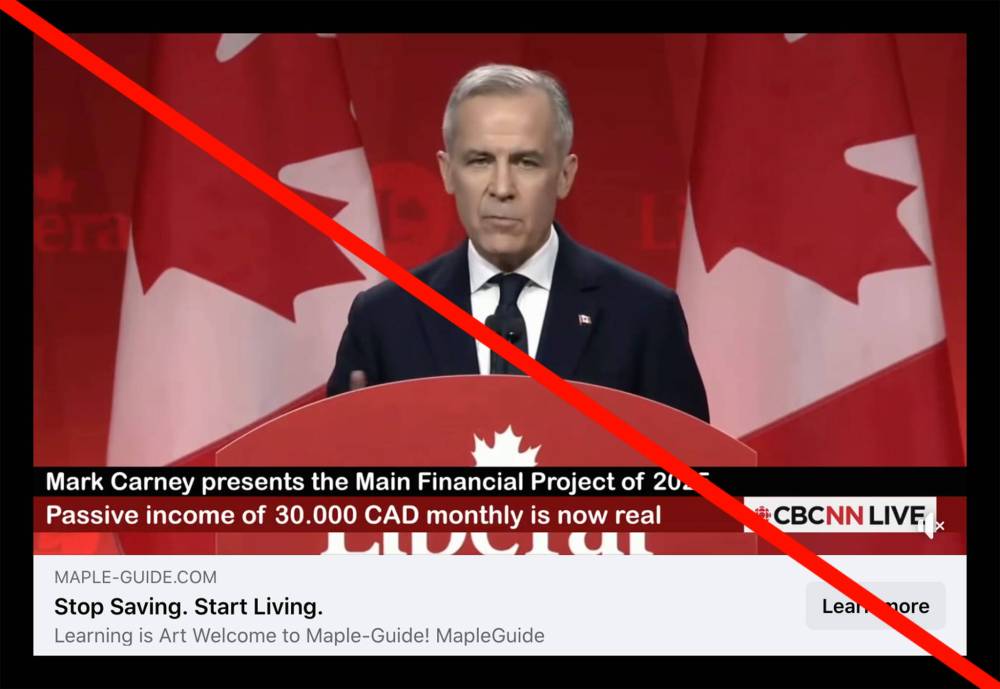

The video features a man who looks a lot like Liberal leader Mark Carney at a podium with Liberal party branding, flanked by Canadian flags. It’s styled to look like a clip of a press conference on CBC News Network, with a news ticker that reads “Mark Carney presents the Main Financial Project of 2025.”

“Only the bravest can take advantage of this opportunity,” intones a voice that sounds a lot like Carney’s. “When I tell you that you have the chance to earn $1,000 a day for the rest of your life without any investment or special knowledge, you can believe it.”

Can you believe it? Of course not. This is not a video of Mark Carney.

It’s a generative AI deepfake video pushing a passive income scam, and it’s just one of many such ads mimicking legitimate news sources such as CBC and CTV that have been spreading all over Facebook in the leadup to Monday’s federal election.

Troublingly, not all Facebook users seem to know that.

“A liar and a thief,” “Never voted for you,” “You were never vote (sic) in, he is such a slime ball,” “Vote Conservative! ONLY!” reads a sampling of comments on the Carney deepfake video.

Disinformation campaigns are not new. But the use of generative AI is a challenge unique to this election cycle. AI-generated content is more mainstream. It’s more sophisticated. And there is much, much more of it.

Jennie Phillips is the director of the Project on Information Ecosystem Resilience with the Media Ecosystem Observatory, a collaboration between the McGill University and the University of Toronto. The MEO also co-ordinates the Canadian Digital Media Research Network, which has been tracking information manipulation throughout the election campaign.

“But in terms of the election, I’m the incident commander,” she says via Zoom from Montreal.

Incidents are defined as “disruptions to the information ecosystem that could cause, or potentially could cause harm to Canadians, to the political system, to the electoral process, to democracy,” Phillips says. Her team’s job is to flag, monitor, determine the severity level of these incidents and respond.

Fake news content on Facebook, for example, has been escalated to a moderate-level incident, Phillips says. Not only is there more of it, she says, it’s also more political and more sophisticated.

The Canadian Digital Media Research Network has identified 75 Facebook pages that have published ads masquerading as legitimate news sources with links to cryptocurrency scams since the start of the 2025 election campaign. Some of these ads get more than 2,400 reactions and 500 comments, Phillips says.

“When you really look at the engagement in these posts, some people put a smiley or a laughing face, but then there’s a lot of people that take it seriously, and a lot of people that share it.”

This type of content is not limited to Facebook, which hasn’t allowed Canadian news on its platform since 2023.

“We’ve detected fake avatar accounts that are created on X and TikTok,” Phillips says. “These are just big accounts that are running divisive narratives during the election. We’ve detected a lot of deepfakes, just in general, of politicians. You might have seen the one going around where it was saying that Carney is satanic — that one was awful.”

One no longer needs to be particularly proficient in artificial-intelligence tools to be able to make their own deepfakes and other potentially harmful content. Phillips points to recent updates to ChatGPT, for example, that have made it even easier for people to create fake images of politicians.

“The more raunchy or the more disturbing, that’s the stuff that spreads.”–Jennie Phillips

“We shifted from AI being this superfluous imaginary idea to now anybody can use it,” she says. “It’s on our phones. It’s embedded in our everyday lives. But now, the tools are also so powerful — and they’re free.”

And that lowered barrier to entry has meant a much greater volume of content, giving the sensation of disinformation whack-a-mole.

MEO is also monitoring the origin of the content, which mostly seems to be private companies outside of Canada, Phillips says.

“We’re curious to see if there’s more going on behind the scenes than just these international fake companies that we don’t really know anything about, and is this actually something more co-ordinated that we should be concerned about.”

Like all content creators, bad actors creating disinformation deepfakes and divisive memes are at the whims of the algorithm on any given platform. The more provocative the post, the higher probability it’ll go viral — helped along by people who might just be sharing it for a laugh.

“The more raunchy or the more disturbing, that’s the stuff that spreads,” Phillips says. “It might start funny and start entertaining, but it’s the stuff that’s catchy and that’s the stuff that we need to be concerned about, because someone down the line is gonna be believing it.”

In order to understand why this kind of content thrives online, it’s useful to understand the culture in which it is created.

Jason Hannan is a professor in the department of rhetoric, writing and communications at the University of Winnipeg. He is also the author of the 2023 book Trolling Ourselves to Death: Democracy in the Age of Social Media, which examines disinformation, conspiracy theory, populism, cancel culture and public shaming through the lens of trolling.

Trolls are no longer anonymous internet pot-stirrers deliberately posting offensive or provocative messages, Hannan argues. They can be public figures, including politicians.

Hannan’s book is a spiritual sequel to American media theorist and cultural critic Neil Postman’s 1985 polemic Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, which argued television transformed media and politics into forms of entertainment, degrading the quality of public discourse in the process.

“Argument, as a kind of intellectual ideal, got replaced by entertainment, so the more entertaining a politician, the more likely they were to win an election, right?” Hannan says. “So I tried to build on that argument by asking, well, what difference does social media make? I have argued that it has intensified, in many ways, the degradation of public discourse, in part by fragmenting public speech, by fragmenting public memory.”

Indeed, how we consume information has changed dramatically with the advent of even smaller screens we keep in our pockets. Short television sound bites have been replaced by even shorter bits on TikTok and Instagram that people might glance at before scrolling on, Hannan says.

“And the consequence of this highly fragmented discursive arena is that the louder, the sillier, the more juvenile your speech, the more likely it will be to prevail,” he says. “The old order has been upended, and we’re now in this kind of political playground in which immature personalities can do very, very well.”

Loneliness and isolation play a role, as well. Though not new societal problems, they have been exacerbated by an increasingly solitary and online existence and, in 2020, a global pandemic that kept everyone apart. And lonely people who feel excluded by society, forgotten or paranoid can be especially susceptible to conspiracy beliefs.

Hannan says COVID-19 gave us a glimpse into just how vulnerable Canadians were to conspiracy theories. On social media, anti-vaccine and anti-science misinformation spread as quickly as the virus.

“I think things have only gotten worse. Unfortunately, we now know that a very large number of Canadians just do not have the basic media literacy skills and digital literacy skills to tell the difference between fact and fiction, between reality and conspiracy theory.”

That leaves a lot of room for disinformation to take root, especially as Canadians continue to rely heavily on social media for their news and political content “often unaware of the broader implications of platform-driven changes on their information consumption,” according to a MEO brief from March.

“Our biggest concern here is, is there something behind the scenes that could be co-ordinated that could be looking to disrupt perceptions of Canadians?” Phillips of the MEO says.

“And ultimately, whether or not that’s happening, the outcome of this fake generative content is it ‘is’ influencing beliefs, whether we like it or not. We just hope that it’s not influencing them enough to cause a shift in what people should believe if they’re accurately informed.”

And an informed public is the foundation on which democracy rests.

“If the citizenry is uninformed — or worse, disinformed — then it’s going to be impossible for us to make informed choices when we go to the voting booth,” Hannan says.

“This is why journalism, for example, has often been celebrated as the fourth estate. It’s absolutely crucial. You can’t have a society as large as modern liberal democracies without having reliable journalism to keep us as citizens informed because we do not have the time to travel personally to Ottawa and meet with politicians directly. We rely on the intermediary of journalists to keep us informed about politics, about the economy, about public health, about so many different aspects of our society.”

Access to and the production of quality journalism has become more difficult over the last several years owing to a Gordian knot of issues.

Deep cuts to newsrooms have meant fewer reporters, who are forced into a constant state of reactivity to keep up with ever-faster news cycles. As local news outlets dry up entirely, news deserts have spread.

In the era of U.S. President Donald Trump 1.0., “fake news” became a rallying cry not against disinformation posts the likes of which are being discussed here, but rather against legacy media institutions. Now, it’s becoming common practice for politicians to bar access, whether it’s Trump punting the Associated Press from the Oval Office or Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre blocking journalists from travelling on the party’s campaign plane.

There is also what Hannan calls a “paranoid assault on journalism” perpetuated on social media.

“We now have conspiracy theories about newspapers, news organizations and journalists,” Hannan says. “The idea that they can’t be trusted, they’re part of the machinery, the apparatus of oppression, and therefore we need to get through quote-unquote real news from some guy on YouTube.”

“If the citizenry is uninformed, or worse, disinformed, then it’s going to be impossible for us to make informed choices when we go to the voting booth.” –Jason Hannan

And on some platforms, there’s no real news to offset the fake stuff.

In 2023, Meta, the company that owns Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, banned access to news on its platforms for Canadian users in response to the Online News Act. That ban is still in effect.

One might think that Meta’s news ban might twig people to the fact fake AI-generated ads posing as legitimate news sites wouldn’t be visible to them. But even that is a source of conspiracy thinking.

“There was one thread that we came across where people were wondering, ‘Well, there’s a news block on Meta, so how is CBC getting in? Do they have some sort of secret arrangement with Meta that they can allow their news to pop through?’” Phillips says.

You’d also have to know Meta was blocking news.

According to a MEO report from August 2024, only 22 per cent of Canadians knew that news was banned on Facebook and Instagram. At that point, the ban had been in place for a year.

Obviously, these platforms aren’t going away and millions of Canadians will continue to use them. So what can we do?

In addition to diversifying our news consumption and thinking more critically about what we encounter online, Phillips says it’s helpful to think of this content — whether it’s AI-generated fake news clips, manipulated stories or misleading images or videos — as a virus.

We can dust off the guidelines we were given during the pandemic. Stop the spread. Look for symptoms of fake content. Report it.

In the win pile, about 60 per cent of Canadians who believe they have seen the ads mimicking legitimate news sources say they immediately recognized them as false, per the Canadian Digital Media Research Network’s most recent update. But that might become harder to do as the volume of these kinds of posts increases.

“We’re almost at a state of crisis in terms of democracy,” Phillips says. “We rely on accurate information to maintain our democracy, so being able to detect this type of information and respond to it accordingly and mitigate the spread, it’s just like a pandemic. Just as we want to keep a healthy society, we want to keep a healthy ecosystem.”

As for why Canadians should care about this issue, Hannan says the answer is obvious.

“What happened in the United States in 2016 and what happened again in 2024, where a pathological liar who has the most abusive relationship imaginable to fact, truth, reality and evidence got elected, not once, but twice,” Hannan says.

“When we normalize a disregard for truth and fact, we are creating the conditions for political extremism, which is what we’re seeing in the United States.”

jen.zoratti@winnipegfreepress.com

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.