Speakers need to become teachers

Schools work to fulfil promise afforded by new law supporting Indigenous language

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

‘Minawaanigoziwin” is the Ojibwa concept that comes to mind for Sherri Denysuik when the Winnipeg teacher is asked about her thoughts on a new law that raises the status of Indigenous languages in schools.

That term is roughly translated to “one who is happy and joyous.”

Denysuik, a member of Sagkeeng First Nation, is trying to learn words many of her ancestors were banned from speaking and, in many cases, punished for uttering inside a residential school.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS FILES

The province is meeting with leaders and academics from post-secondary education programs to sort out its next steps in producing more Indigenous language teachers.

Recent changes to Manitoba’s Public Schools Act are expected to make it easier for future generations to become fluent in Indigenous languages.

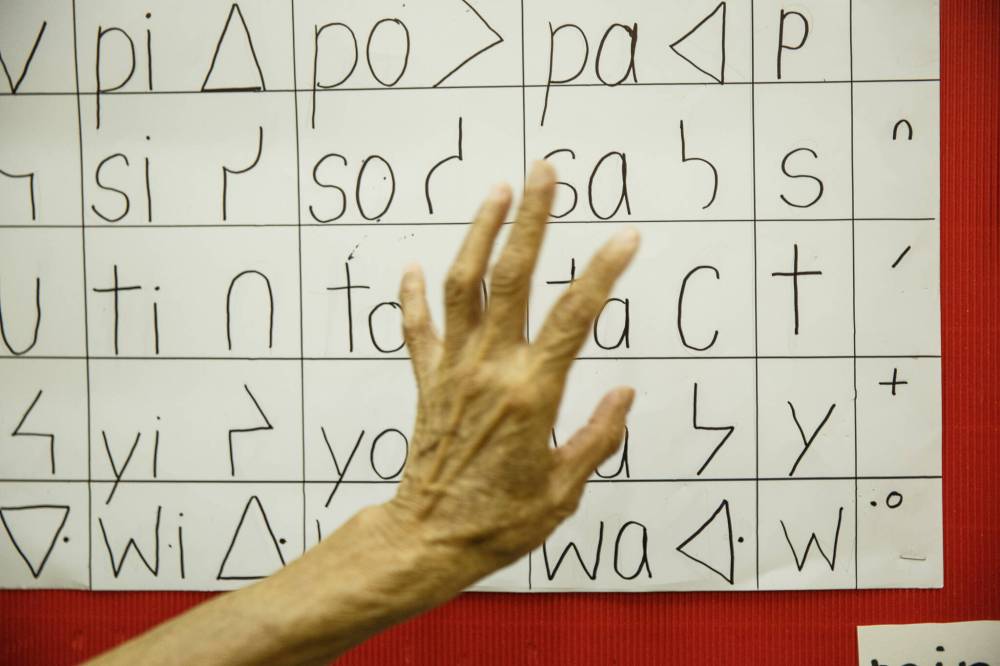

Bill 18 places Ojibwa, Cree and others in the company of Canada’s official languages in the kindergarten-to-Grade 12 system. It allows schools to teach an Indigenous language for more than 50 per cent of an instructional day.

English and French were previously the only “language of instruction” options, although there are immersion programs — for example, Filipino, Ukrainian and Punjabi streams in the Seven Oaks School Division.

Seven Oaks held its first Ojibwa immersion class in 2016 at Riverbend Community School (also known as Riverbend Gikinoo’amaagewigamig).

Denysuik, an assistant superintendent, said the growth of their language programming has been “very organic.” Seven Oaks wants to continue to expand it and there’s high demand, but it’s a huge challenge to find fluent language speakers, she said, noting her employer has been offering training for “emergent speakers.”

Statistics Canada data suggests 13 per cent of the population can speak an Indigenous language well enough to conduct a conversation in it. The number of these language speakers dropped by nearly 11,000 people, between the latest census in 2021 and its 2016 predecessor.

“There’s significant urgency in this work so we’re trying to, in a really good way, balance a pace that’s reflective of that urgency, but in a way that’s thoughtful and respectful,” said Jackie Connell, the assistant deputy minister who oversees Manitoba Education and Early Childhood Learning’s newly established office of “Indigenous Excellence.”

Connell’s team is taking the lead from first-language speakers “and people who’ve been doing this work for generations,” the Red River Métis educator said.

She noted that they have been working with colleagues in the professional certification unit to find a clear, achievable and flexible pathway for fluent speakers to work in K-12 classrooms across the province.

Given it’s currently “really, really tough” to find Indigenous language teachers, there are ongoing discussions about ways to recognize community-based experience in the certification process, she said.

Connell indicated the province is meeting with leaders and academics from post-secondary education programs to brainstorm next steps.

Thompson’s Wapanohk Community School was the first of its kind to — with permission from the department of education — offer Cree instruction in every subject in kindergarten through Grade 8.

Co-principal Brent Badiuk’s advice to others who want to launch a successful Cree school?

“Surround yourself with staff who are very passionate in growing the Cree language and culture,” said the non-Indigenous educator who has spent most of his adult life in northern Manitoba.

Four in 10 classroom teachers on this year’s staff roster are fluent in the language, Badiuk said.

He estimated that 95 per cent or more of the roughly 450 students who attend the elementary school are Indigenous. The majority of the student population is Cree, although there are Dene students, too, he said.

“It sounds like the province is catching up to us (with Bill 18) because this is my sixth year here and the language programming is the same as when I got here,” Badiuk said.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS FILES

Bill 18 allows schools to teach Indigenous language for more than half a day.

He noted that it’s a symbolic moment in that the province has explicitly recognized Indigenous languages in a historic piece of legislation that underpins the K-12 education system.

MLAs should have acted sooner than June — a decade after the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its findings — to acknowledge the importance of Cree and other languages that were being spoken in this country long before English or French, Badiuk added.

The TRC’s 94 calls to action address numerous language-related matters.

No. 10 singles out implementing culturally appropriate curricula and “protecting the right to Aboriginal languages, including the teaching of Aboriginal languages.”

During a phone call in the lead up to Orange Shirt Day 2025, Connell said investing in language revitalization is an important part of reconciliation.

“Historically, there has been a great deal of harm caused by our public education system (and other) places where our languages were outlawed,” she said.

While noting there is significant work required to make Michif and other Indigenous languages as commonplace as English and French, Connell said progress is underway because Premier Wab Kinew is backing this initiative.

Since Connell’s appointment in early 2024, the Indigenous Excellence unit has grown from being staffed by eight employees to nearly two dozen.

Kinew’s government replaced the Indigenous Inclusion Directorate with a government division that is working on numerous projects, one of which is language revitalization.

Notably, the premier is a polyglot who is fluent in English, French and Ojibwa.

Numerous Ojibwa dialects, followed by Michif and Cree, are the most commonly spoken Indigenous languages in Manitoba.

Education Minister Tracy Schmidt officially introduced Indigenous language-related amendments to the Public Schools Act in March. They received royal assent — with little fan-fare — at the end of the 2024-25 school year.

maggie.macintosh@freepress.mb.ca

Maggie Macintosh

Education reporter

Maggie Macintosh reports on education for the Free Press. Originally from Hamilton, Ont., she first reported for the Free Press in 2017. Read more about Maggie.

Funding for the Free Press education reporter comes from the Government of Canada through the Local Journalism Initiative.

Every piece of reporting Maggie produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.