Its healing days are done

Staff and patients shed a tear for former Shriners Hospital that opened in 1949

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/02/2016 (3512 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

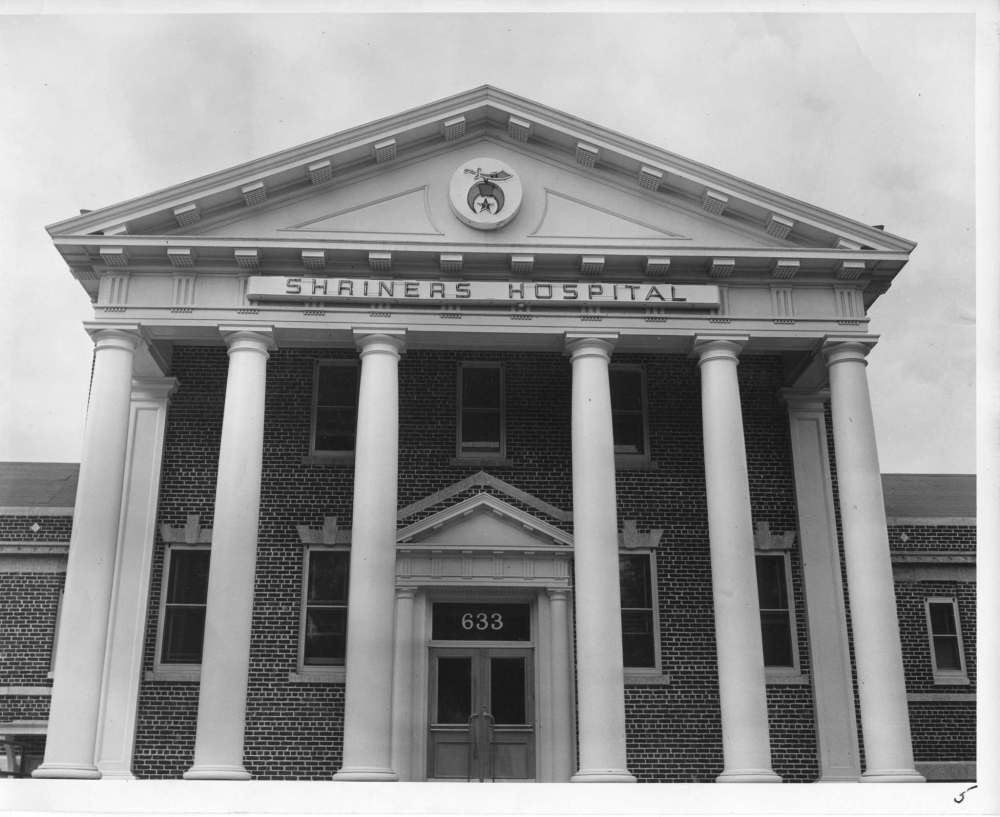

Sometime in the next few weeks, almost seven decades of caring for children will come to an end at 633 Wellington Cres.

When the furniture is removed and the door is locked at the front of the sprawling, red brick facility next to the Assiniboine River, children with mobility issues and other needs will begin being treated elsewhere for the first time since 1949.

“I think it’s the end of a lovely period of time,” physiotherapist Sharron Jordan said. She worked there during the final years it was known as the Shriners Hospital and for more than a decade when it was called the Rehabilitation Centre for Children.

“I will shed a tear. I love the building. Maybe it was quirky and too hot and too cold, but to me, it was like a second home. And it helped a lot of children.”

The new home for the Rehab Centre and other services for children who have special needs will be Specialized Services for Children and Youth on Notre Dame Avenue at the site of the former Christie Biscuit factory.

But on a stretch of a tony street near some of the city’s most valuable homes, whether it was care provided by the Shriners Hospital or later the Rehabilitation Centre for Children, legions of children have been assessed, diagnosed and treated.

The Shriners began opening hospitals in North America in 1922, with the first one in Shreveport, La.

Three years later, Winnipeg opened its first Shriners Hospital, which was a wing of the Children’s Hospital, then located at Main Street and Redwood Avenue.

It had 27 beds, a perennial waiting list of 60 to 75 children, and helped more than 2,700 children in its first 20 years.

When the Shriners were told in 1945 they would have to move the facility out of the hospital because it was inadequate and outmoded, a plan was drawn up to build a stand-alone hospital.

The Shriners’ Imperial Council told their brethren in Winnipeg that if they — and their Western Canadian cousins — could build and pay for a $300,000, 40-bed hospital, they would guarantee the operating expenses in perpetuity.

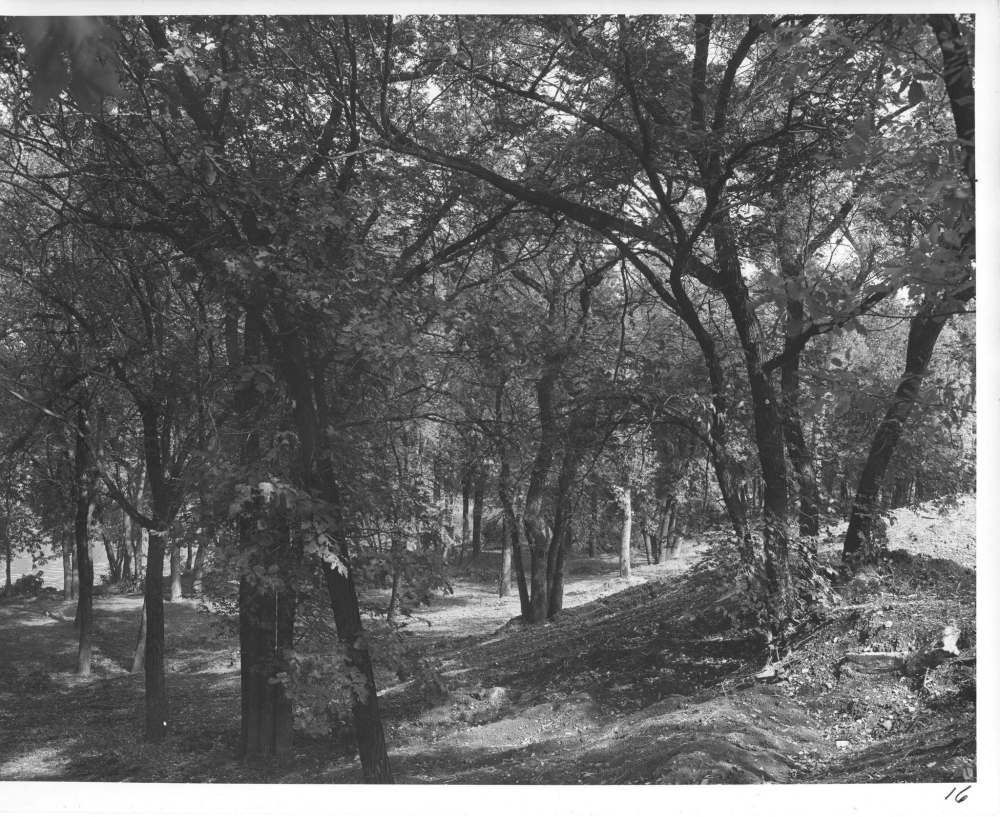

Construction began in May 1947, and it was completed in two years. It was built on the former property of Lt.-Gov. Daniel McMillan — the first president of the Winnipeg Grain Exchange and a former MLA.

His house, which is connected by a tunnel to the former hospital, still stands and is used for offices.

By the time Winnipeg’s hospital officially opened March 29, 1950, it was one of 16 across North America.

The official opening attracted many prominent people, including silent film star Harold Lloyd of the iconic film Safety Last! in which he is high up on the outside of a tall building clutching a clockface. At the time, Lloyd was the imperial potentate for the organization.

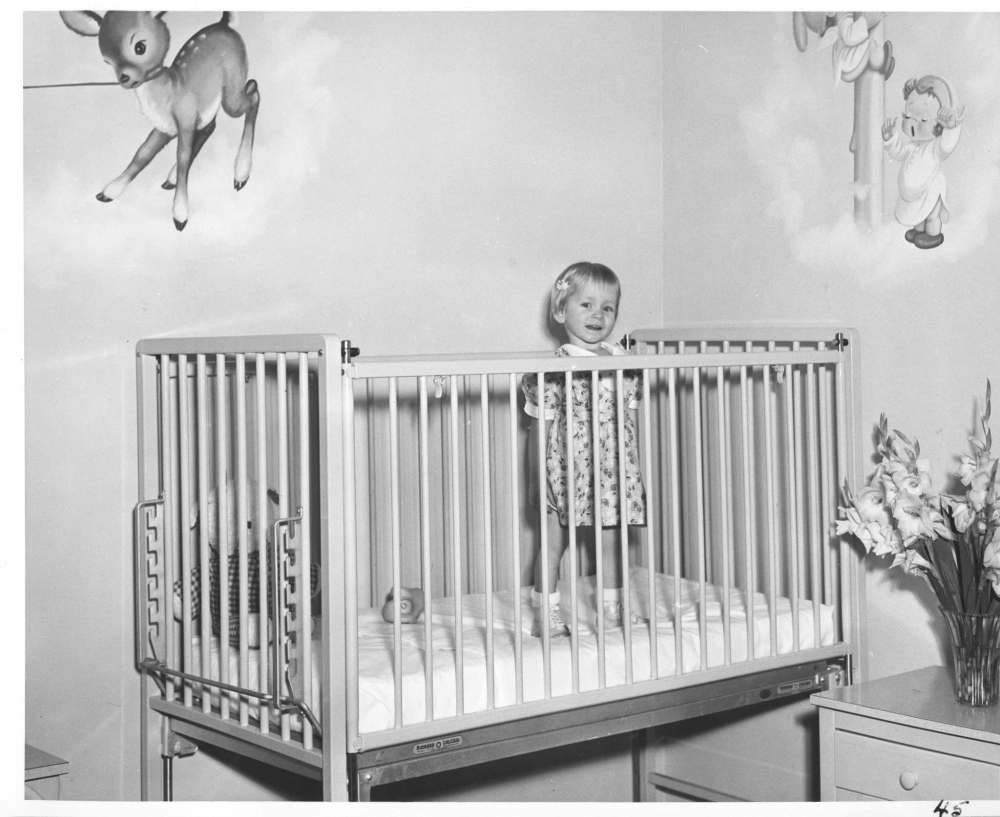

Just two years later, the Shriners needed to expand the bed capacity to 50.

Don Thomson, a former Shriners potentate and current hospital chairman, said Shriners today are still proud to say that shortly after the dedication, the fundraising by Shriners from Northwest Ontario to British Columbia proved to be such a success that the Winnipeg facility became the first Shriners Hospital to be fully paid off when it was turned over to the international organization.

Although it was dedicated in 1950, the hospital opened its doors to young patients on June 9, 1949.

One of its earliest patients was Marge Wright.

“I don’t know if I was the first through the doors, but I was part of the first group to get in,” Wright said recently as she walked through the building for the first time since spending almost two years of her youth there.

“It was such an improvement over the old hospital. This was beautiful.”

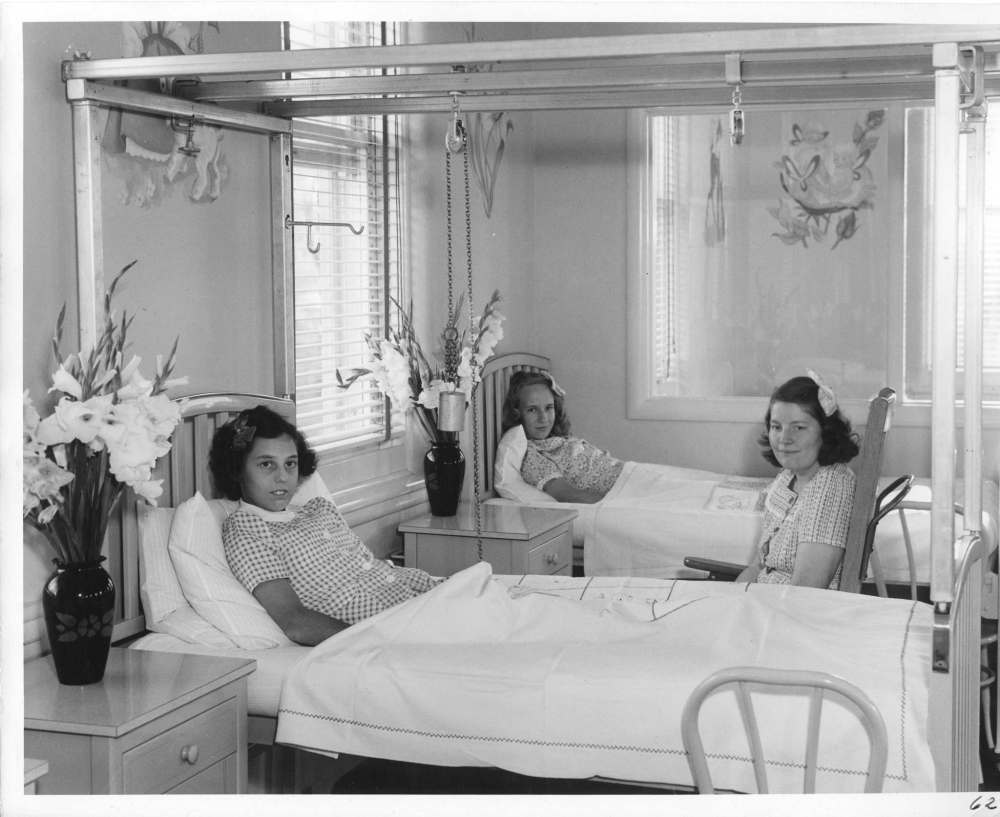

Wright, who was 11 at the time and the youngest of five children, needed surgery to her spine to correct the damage caused by polio.

This was before universal health care, when people had to pay for their treatment. Her widowed mother couldn’t afford it.

A doctor referred her family to the Shriners. The Shriners had vowed to treat any child under 14 whose ailment was of “a curable nature” and who came from a family that couldn’t afford medical treatment.

Wright was accepted, and about a week after her surgery at the Children’s Hospital, she was transferred to the new Shriners Hospital. She was quarantined upon arrival and couldn’t see anyone for two weeks.

“They had put me in a cast from my head to my knees,” she said.

“They shaved my hair because the cast came over my head and only my face and one ear were out.”

She lived that way for a year following surgery. In the second year, the cast went from her shoulders to her waist.

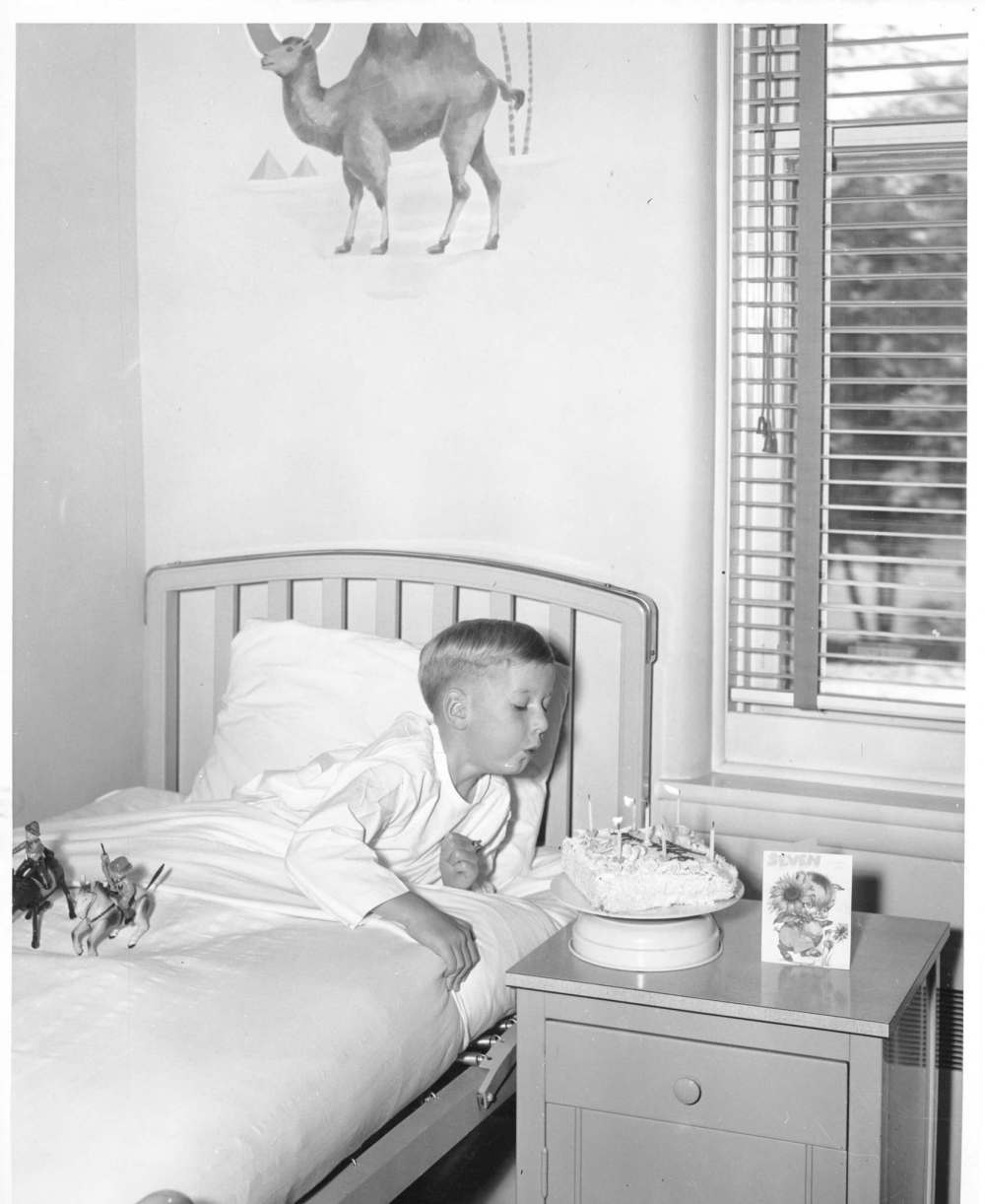

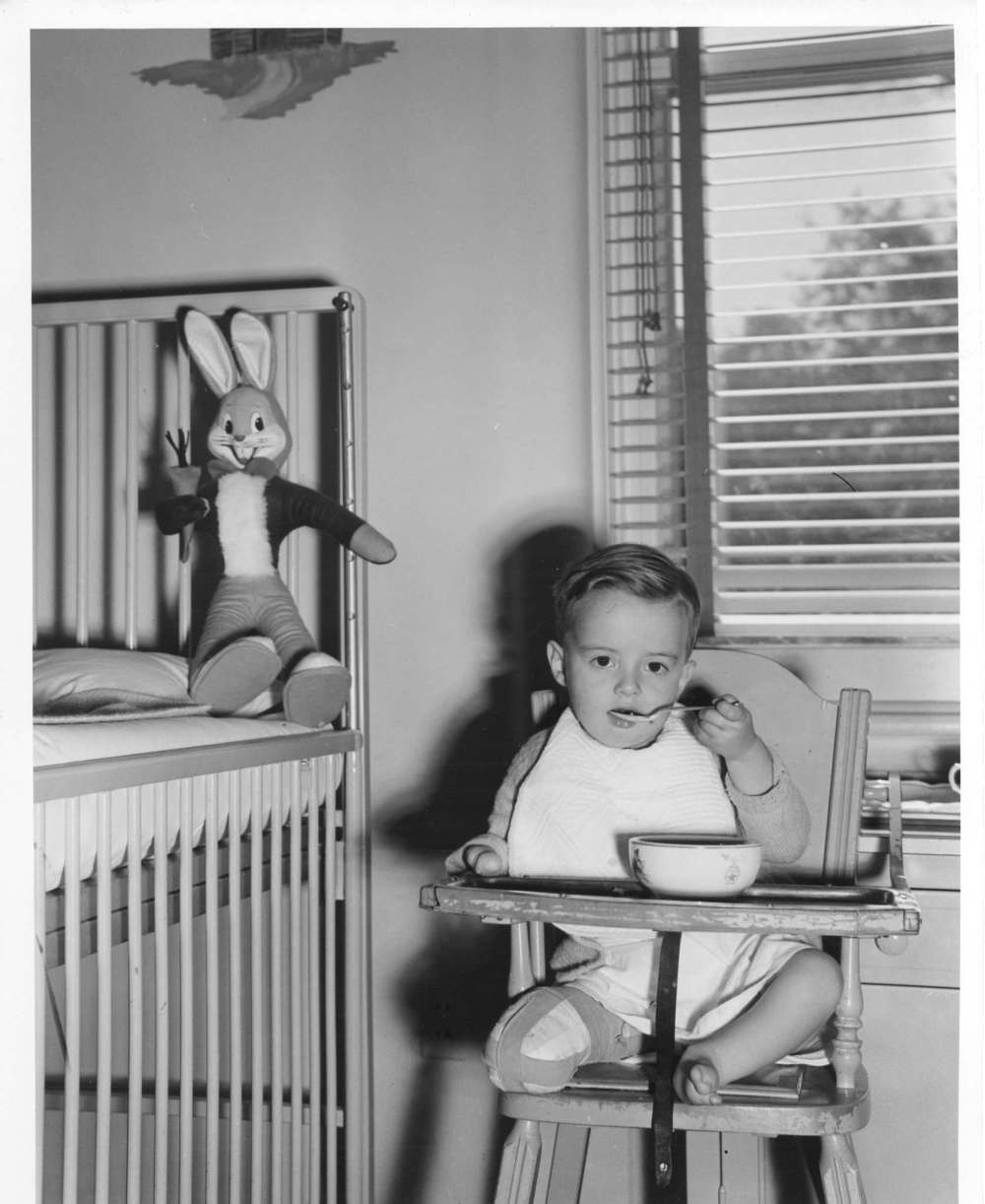

Just because a child is on an extended stay in hospital doesn’t mean they stop being a kid. Wright recalls children buzzing down the hallways in their wheelchairs, sitting up late at night listening to Hockey Night in Canada and sometimes doing things they shouldn’t.

Wright recalled a story she hadn’t told anyone before now.

“I hadn’t had a bath for a year. Another girl and I just wanted to get into a tub so badly. We snuck into the tub room and put enough water in so we could get our bums in. It felt so good. Of course, the bottom of our casts got wet.

“The next day the head nurse said to me ‘How did this cast get wet?’ and then she looked at the other cast and said ‘Here’s another cast that’s wet.’ She must have known, but we never told. I never told — until today.”

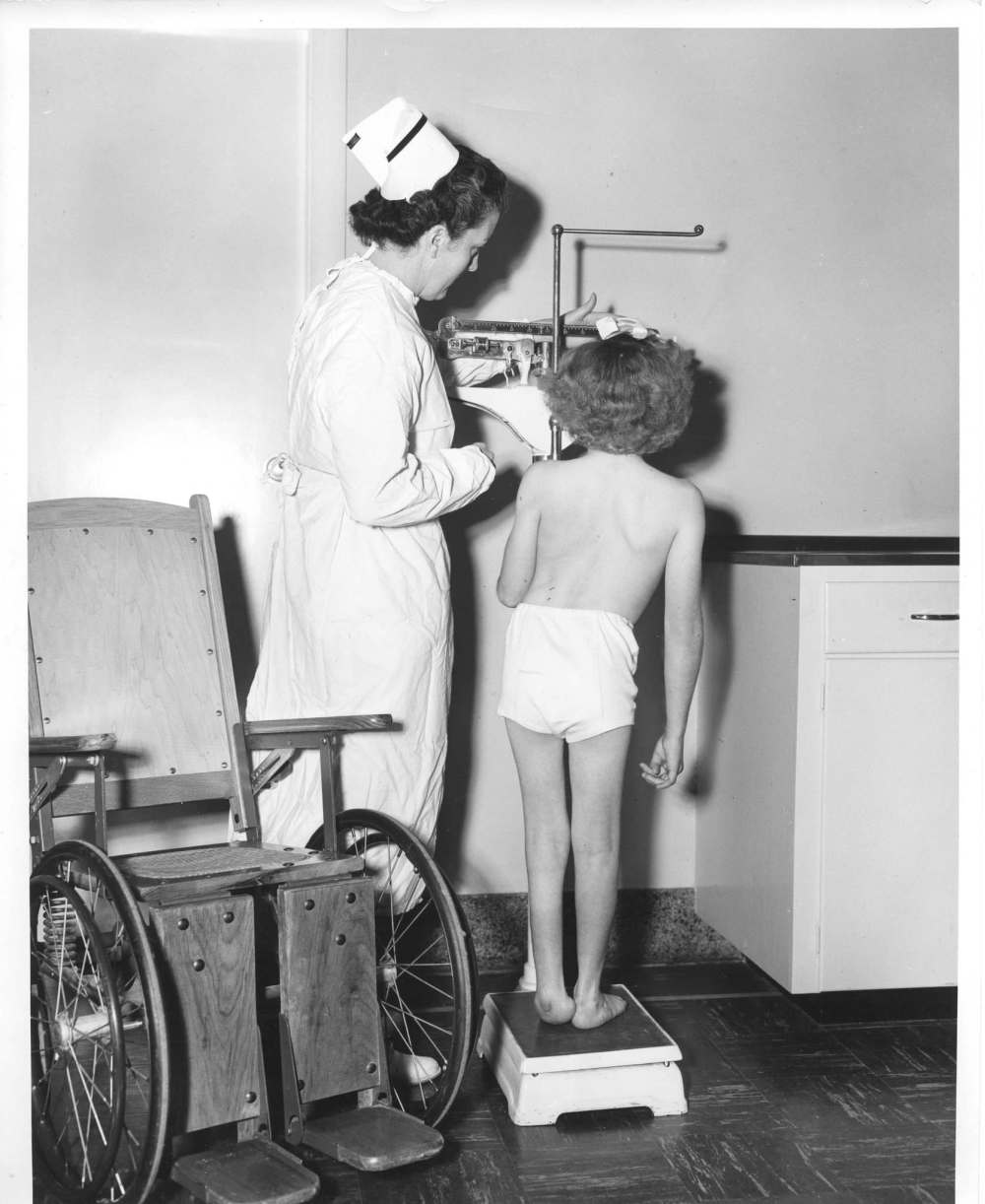

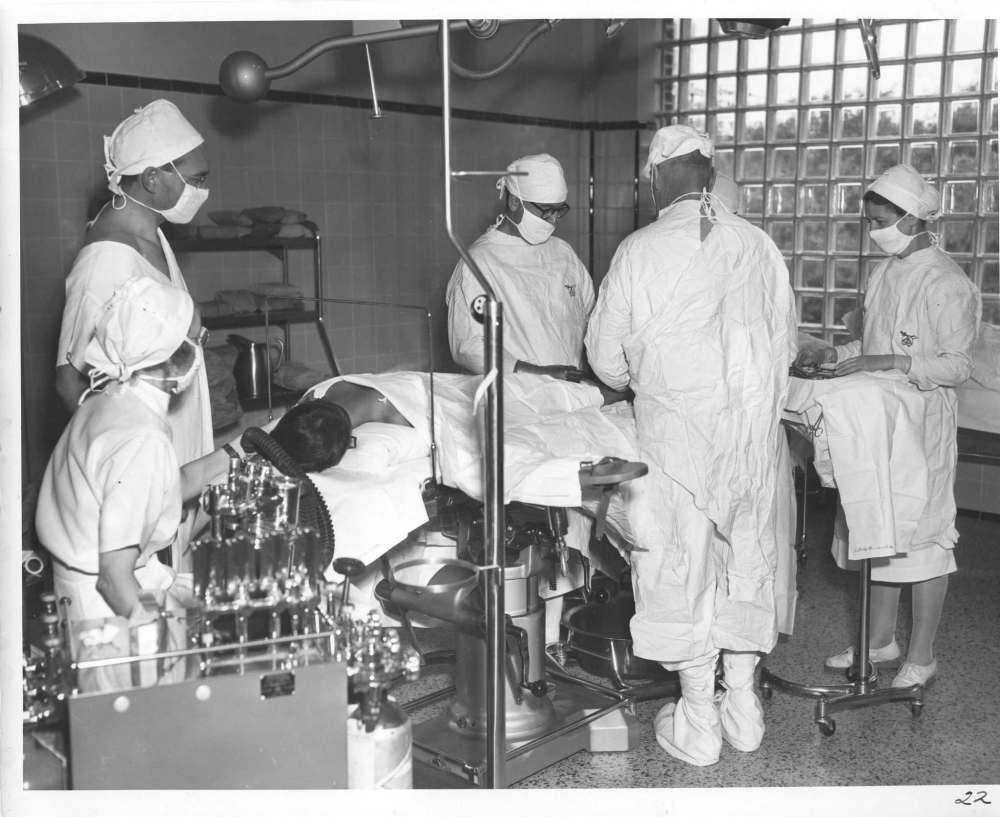

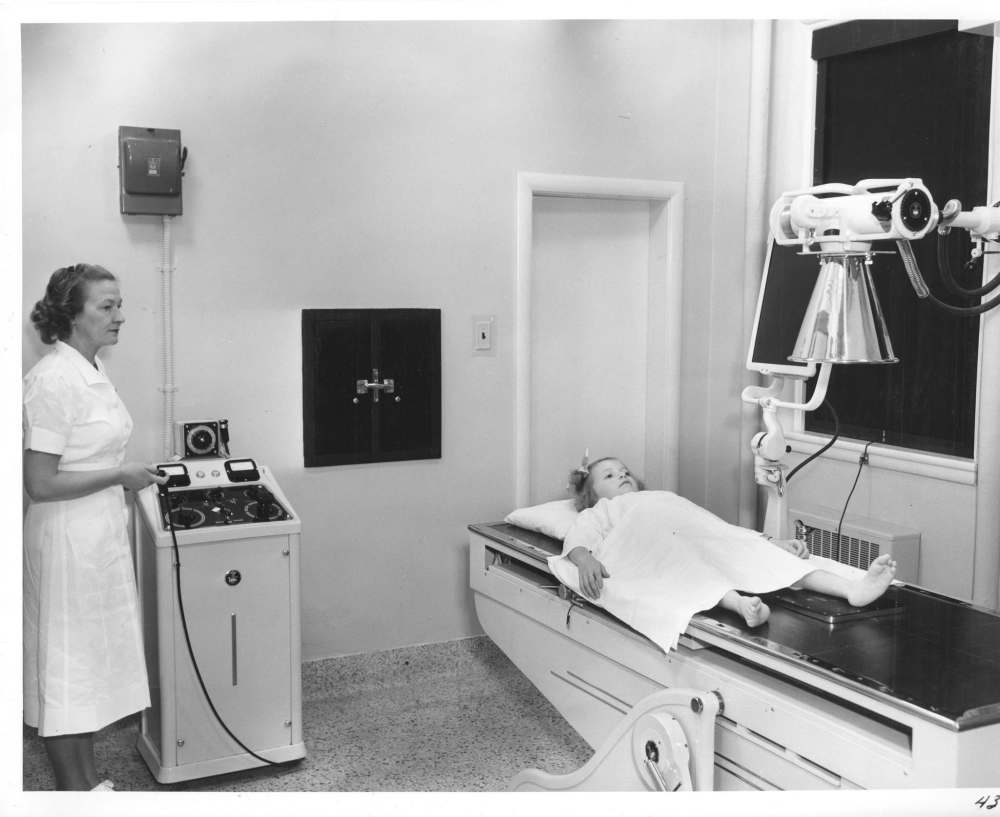

Inside the Shriners Hospital, children were helped by a myriad of skilled specialists. There were orthopedic surgeons performing surgery in operating rooms on the second floor, as well as dentists, nurses, and therapists. There were also people creating braces and prosthetics in workshops.

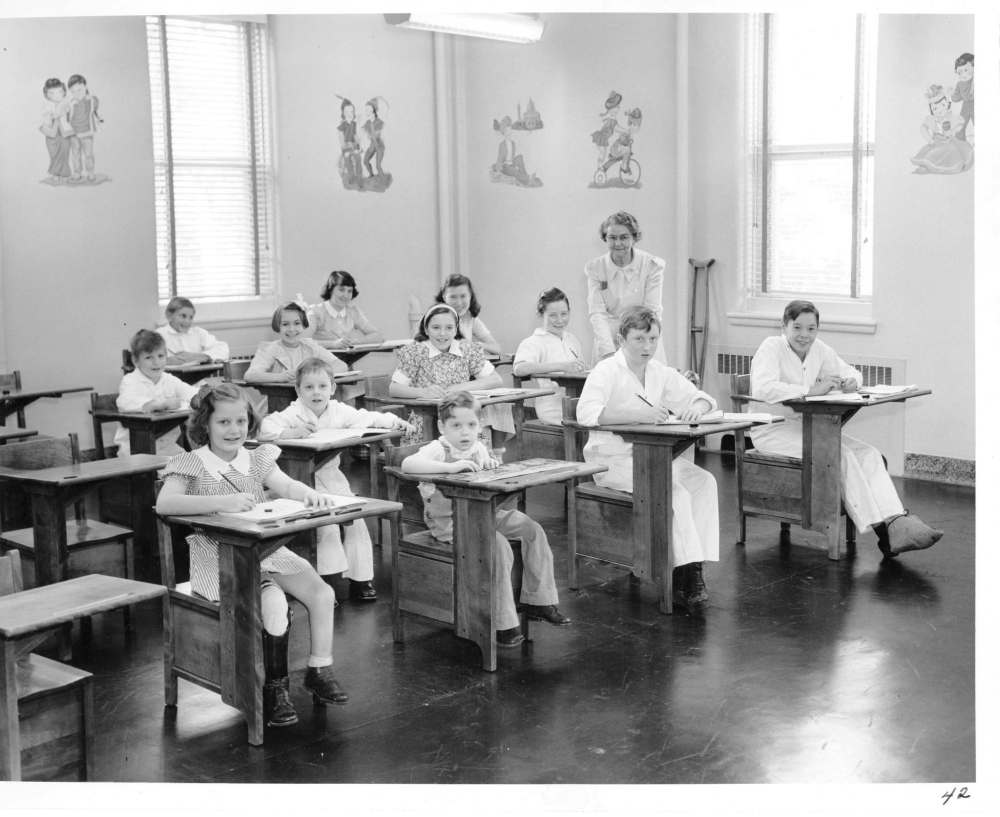

There was a fully equipped classroom, with differently sized desks and a fulltime teacher, on the main floor. The room now is a therapy room filled with different types of equipment for children with mobility issues, but you can still see it was a classroom. The blackboards are still there, but painted over. The ledge for the chalk brushes also remains.

“They just could do basics here,” Wright said.

“There were too many kids of different ages.”

Down a short hallway is a door leading out the back of the building, where a short ramp takes a visitor to a flat deck with a green plastic roof over it.

“We would go out there and we would watch the parades and the circus performer,” Wright said.

Behind the scenes, the Shriners and the Khartum Ladies Auxiliary were the backbone of all of the good work. The Shriners would raise funds to help keep the operation going while their wives, members of the auxiliary, would raise funds and help with the day to day work of the hospital, including sewing hospital gowns.

Arla Sidebottom, who has spent years volunteering with the auxiliary, said she still remembers a team of ladies manning sewing machines in a room dedicated to their volunteer work.

“They would make hospital gowns for the patients, but they would also make sure that every child received a complete outfit when they left,” she said.

“They were in there every week. The machines were going full tilt to get the gowns made. The Cub scarves. They outfitted all the children. It was just wonderful.

“They (the sewers) were devastated when the hospital was transferred, just devastated.”

Sidebottom said the auxiliary funded the dental clinic in the facility from 1952 to 1976.

But she said even now, decades after the hospital was transferred, the auxiliary still holds its monthly meetings there.

Darlene Borowski, another volunteer with the auxiliary, said the organization is 91 years old and while the hospital is gone it still supports the Shriners Patient Transportation Fund and helping to buy equipment for the Rehab Centre.

Borowski said they also provide a trip bag with travel items and toys for every child that flies out of Winnipeg to get treatment at a Shriners’ Hospital.

Wright said she remembers visiting hours were restricted to once a week on Sunday and only for two hours from 2 p.m. to 4 p.m.

“I had only two exceptions during my time there. One was the American singer Frankie Laine (who sang That’s My Desire),” she said.

“He was my idol. He came to the city to sing at Don Carlos and friends told him about me so he came to see me.

“The other was the brother of my dad from Chicago. He came to see me so they let him in on a Wednesday. But they were the only people I saw when it wasn’t Sunday.”

The only other way Wright could see people was to look out her window.

“A couple of my school friends would come and talk to me through the window,” she said.

A radio was Wright’s link to the outside world.

“I was older so I was allowed to have a radio,” she said.

“The older boys would come down to our end of the hospital when hockey was on. They would sit on the floor and listen very quietly so we didn’t wake the younger ones. I could name anyone on the teams back then.”

Wright recalled how the nurses would come up with ways to help the children through the weeks and months they were there.

She said one child would have regular meltdowns and would try to hurt herself.

“Only during those times would she speak in an Irish brogue. They were putting her in a restraining vest, but then they found if they gave her a box with a lid she would stop. All the nurses would bring in boxes. I wonder now if the girl was autistic.”

By the 1970s, things had changed in Canada. Canadians no longer had to pay for medical treatment or hospital bills. Instead of a waiting list for the beds, the number of children actually being treated in the Shriners Hospital dropped to seven.

“The need for a hospital providing free care was no longer viable,” Thomson said.

“There was one in Minneapolis, too, which isn’t that far from here. It’s too bad because this one would have served a greater area from Northwestern Ontario to British Columbia.”

The Shriners made the decision to turn over the building to the provincial government for a dollar. It became official on July 27, 1977, when the name changed from Shriners Hospital to Rehabilitation Centre for Children.

Both Arla, and her husband, Tom, remember how both the men and women of the organizations felt when the keys to the building were turned over and it was no longer their facility.

“It devastated the auxiliary when it closed,” Sidebottom said.

“We were hands on. We were right there with the kids.”

Tom, a past Shriners potentate here, has spent 58 years as a Shriner, but his first two decades he went to the hospital many times.

“You had a couple of hours off from your job and you would come in. I went into the Shriners in 1958 and I spent many a happy time there.

“The hospital is where we all got the bug to be with Shriners. To come here and play with the kids was great. And you could really see all the things they talked about at meetings.

“A couple of hours with the kids really told you what the Shriners were all about.”

But Tom said he isn’t upset the site will likely be bulldozed and redeveloped into something else, such as a high-rise condominium development.

“There’s no hard feelings,” he said.

“It had its time.”

While the name and ownership changed, caring for children didn’t. In fact, much stayed the same for the first few years when the banner became the Rehabilitation Centre for Children. The Rehab Centre even had a 20-bed in-patient unit for its first few years as well as many other services and clinics pioneered by the Shriners here.

Walking inside the building today, the entrance foyer still looks much the same as the day it opened. An opening to the right still has the building’s receptionist, a display case is next to it, and on the other side is the door to offices.

Set into the terrazzo floor is the Shriner’s crest featuring a fez and a scimitar.

When it was the hospital, turn left and go to the end of the hall, you would find the girl’s wing. Today, as the Rehab Centre, you would see children getting their bones and muscles assessed or having their nutrition intake monitored by feeding specialists.

Turn right, and you would end up in the boy’s wing. Today it is a large room where a day program has operated and a room for therapy.

The basement, where laundry was done and aquatic therapy was performed, is now the wheelchair and equipment assessment rooms for children living with special needs as well as the shop for making the devices.

Along the top wall of the shop remains the palm trees and fish motif for the aquatic area.

It’s a bustling place. Children and youth are going through the doors — or up and down the outside ramp — numerous times a day. They see therapists, feeding specialists, and bone and muscle doctors. They get fitted for orthotics and prosthetics. There is a spina bifida clinic and the Manitoba FASD Centre is housed inside the building.

“It is focused on services for children with all sorts of disabilities,” said Cheryl Susinski, the Rehab Centre’s executive director.

“We want to help children participate as fully as possible in the community.”

Susinski said while the centre has branched into many different areas since the Shriners left, “we’ve always maintained the core services they had.

“And we’ve always moved to integrate the services. We have evolved through the years, but we still have our roots firmly entrenched in what the Shriners offered.”

The Rehab Centre gets more than 20,000 visits per year, but Susinski said a big change through the years is a reduction in the number of children who have to travel to Wellington Crescent for services. She said occupational and physiotherapists travel to schools in the city as well as heading up north or to rural communities.

“Probably two-thirds of the children we see are outside the facility,” she said.

“We try to be where the kids are. We work with teachers, with educational assistants and with parents.”

Susinski said the move to the new facility on Notre Dame Avenue isn’t necessary just because the riverbank erosion in its back yard is creeping slowly towards the current building — it has already consumed what used to be its parking lot and made a garage with apartments for out-of-town parents unsafe to use.

“The existing building can’t accommodate the integrated services we now want. We don’t have the room to move in with others that are complementary.”

Gay Kirby began working at the Rehab Centre a year after the Shriners left until retiring a few years ago as the executive director of its fundraising arm, then called the Rehabilitation Centre for Children Foundation and now the Children’s Rehabilitation Foundation.

“I think we’re the only place in Canada which separates rehabilitation from acute care,” she said.

“We always felt we were the best kept secret in Manitoba. We were cutting edge with looking after these children.”

Kirby said long before various devices to help children living with special needs — such as a bath chair or a support to help a child sit up in a wheelchair — became commercially available, engineers and craftspeople designed and produced them in their shop.

“We found once a child could sit properly, they could begin doing more,” she said.

“We wanted to see the child before the technology. I think what they do there is miraculous.”

Jordan said while both the Shriners Hospital and the Rehab Centre help children living with disabilities, there was a difference in focus between the two organizations.

“With the Shriners, we had an operating room and nurses. We had rounds. The physiotherapy helped after surgery. We had outpatients, but we had a lot of inpatients.”

Jordan said in addition to the predominantly outpatient services the Rehab Centre does today, there is one other function it does well.

“It is a more comfortable and home-like place for the parents and children to go to,” she said.

“I hope that continues.”

At least one of the items in the Rehab Centre that made it friendly is moving to the new facility on Notre Dame Avenue.

And its name is Sandy.

Sandy is a coin-operated horse, the kind that always in front of department stores. In this case, Sandy was used as an incentive for the children who needed to have their limbs painfully pushed down for X-rays.

Luc Savoie, who was born with cerebral palsy, was thrilled to hear Sandy would be in the new building. The now 22-year-old said when he was younger he spent many times riding on the horse.

“I had a lot of X-rays there,” he said.

“I would just be freaking out because I didn’t like lying on my back. And I have a fear of heights. There was pain too. So when I was told I needed to have an X-ray it would be ‘Oh no, but at least I get to ride Sandy.’”

Savoie said he remembers the horse’s movement would help him relax. “All the nervousness went away,” he said.

“It really made life a lot easier,” recalled Savoie’s dad Joseph.

“If he toughed it out he could ride Sandy. Sandy made it easier for us and made it more enjoyable to go there.”

Savoie said as he grew — he is now more than five feet tall — he could no longer ride Sandy before an X-ray. But the horse still helped him.

“I would just visit with her in the waiting room. I would just reminisce about the times I would ride her. Even that helped. And seeing the faces of the other children there I could say I can do it.”

***

Whether it was with the children in the Shriners Hospital or later the Rehab Centre, life went on while children healed or received therapy.

By the time Wright was discharged her mother had remarried.

But one thing never changed after Wright’s time at the Shriners Hospital.

“I’ve never had any problems with my back,” she said.

“They said you’ll have trouble having children because of your spine, but having children was the easiest thing I ever did. And I have three great-grandchildren now.

“And I always talk to Shriners no matter where I am. I just have to say thank you.”

kevin.rollason@freepress.mb.ca

Kevin Rollason is a general assignment reporter at the Free Press. He graduated from Western University with a Masters of Journalism in 1985 and worked at the Winnipeg Sun until 1988, when he joined the Free Press. He has served as the Free Press’s city hall and law courts reporter and has won several awards, including a National Newspaper Award. Read more about Kevin.

Every piece of reporting Kevin produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.