British reserve, Canadian verve

While our 150th birthday party is a big, colourful celebration from coast to coast, 'Dominion Day' began with respectful restraint in this 'colony'

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified:

By: Randy Turner

Posted:

Last Modified:

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 29/06/2017 (3128 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s safe to say what is now called Canada Day had modest beginnings in these parts.

As far back as 1869 — two years after Confederation and one year before Manitoba was born — the July 3 issue of the Nor’Wester, the paper of record for the “Colony of Assiniboia,” dutifully reported that celebrations on July 1 were muted.

“Dominion Day was kept in our little town by the raising of the ‘Canadian’ flag upon the now celebrated staff — said to be 70 feet, be the same 20 feet more or less — which flag was liberal sainted during the day by an ‘Anvil Chorus’ adapted to ‘God Save the Queen’ and ‘Hurrah! for the New Dominion,” the paper noted. “The affair was wound up by a large bonfire in the evening.

“Not a gun was heard, or a funeral note or anything else,” the account added, “but then you see the H.B.C. (Hudson Bay Company) is keeping her patriotism like champagne, well bottled and wired down, for a future occasion, when we may expect to see it burst forth in a manner calculated to astonish the natives.”

Of course, these were the days of the Riel Rebellion in the Red River Colony. Not exactly the time to be popping that “champagne” in public. Besides, the majority of the less than 1,000 colony settlers considered themselves British. And a vast majority of residents, the Métis under Riel, were literally at war with the new Canada.

In fact, the first widespread acknowledgment of Dominion Day in Manitoba didn’t occur until 1871.

“The Anniversary of the Dominion of Canada,” a notice in the Free Press proclaimed, “will be celebrated in the Town of Winnipeg on Saturday, July 1st, 1871 by Horse Races, Trotting Matches, Running Matches, Foot Races, Standing Jumps, Running Jumps, High Leap, Sack and Blindfold Races, Climbing the Greasy Pole, Putting the Stone, Quoits, a Cricket Match, Football, Throwing the Sledge, etc.”

Cannons were fired from Fort Garry at sunrise. By noon the area in front of Fort Garry was standing-room only. At night, firemen from the fort led a torchlight parade.

When small hamlets began to sprout up across the rural prairies, with the arrival of the railway to the West, each community would hold their own Dominion Day events — one of the few truly Canadian celebrations experienced by newcomers.

Emma Louisa Averill, for example, had just arrived in Minnedosa with her young family after a long journey from England in late-June 1880. Her husband, Octavius, immediately set out searching for a plot of farmland, only to lose the oxen. He walked back to town just before July 1.

“This was the first fete held in Minnedosa in commemoration of the event & the first ox ever killed in the town was in honor of this day,” Averill wrote in her diary. “There were to be sports & various kinds of amusements. By the afternoon there were many more people than I expected to see being strangers of course we knew none of them, but I imagine some must have come a long distance. What I thought the most attractive part of the programme was the horse race in which the costumes were various, one rider being in jockey dress of pale blue & another on Indian, in his own gay dress & who rode his saddleless horse with such an easy grace, that he might have been part of the animal.”

Sure, there’s nothing like climbing a greasy pole or killing an ox to express devotion to flag and country. But for the most part, Dominion Day in Manitoba — not officially called Canada Day until 1982 — was, for the most part, simply considered a welcome personal day. No sombre reflection, gift-wrapping or suit-wearing required.

“It was picnics, races, barbecues, those types of activities,” says Matthew Hayday, associate chair in the department of history at the University of Guelph, in Ontario. “With the exception of 1927 (the diamond jubilee), the federal government basically didn’t do anything in terms of celebrating.

“Dominion Day wasn’t the big celebration on the calender, as far as holidays went,” adds Hayday, co-editor of Celebrating Canada: Holidays, National Days and the Crafting of Identities. “I mean, the Queen’s birthday (Victoria Day, the last Monday preceding May 25) was considered to be more important.”

Even Empire Day, first celebrated in 1899 (which was associated with imperialism and immigrant assimilation), was more equated with Canadian identity. In 1950, Empire Day morphed into Citizenship Day, celebrated on the Friday before Victoria Day in late May.

“That’s the patriotic event that you can actually organize school activities (around),” Hayday says. “In July school’s out and you can’t do things with children, and children are big targets for these types of activities.”

By the turn of the 20th century, thousands of Winnipeggers were flocking to Winnipeg Beach by train. Assiniboine Park became the Dominion Day destination for thousands more after it opened in 1909.

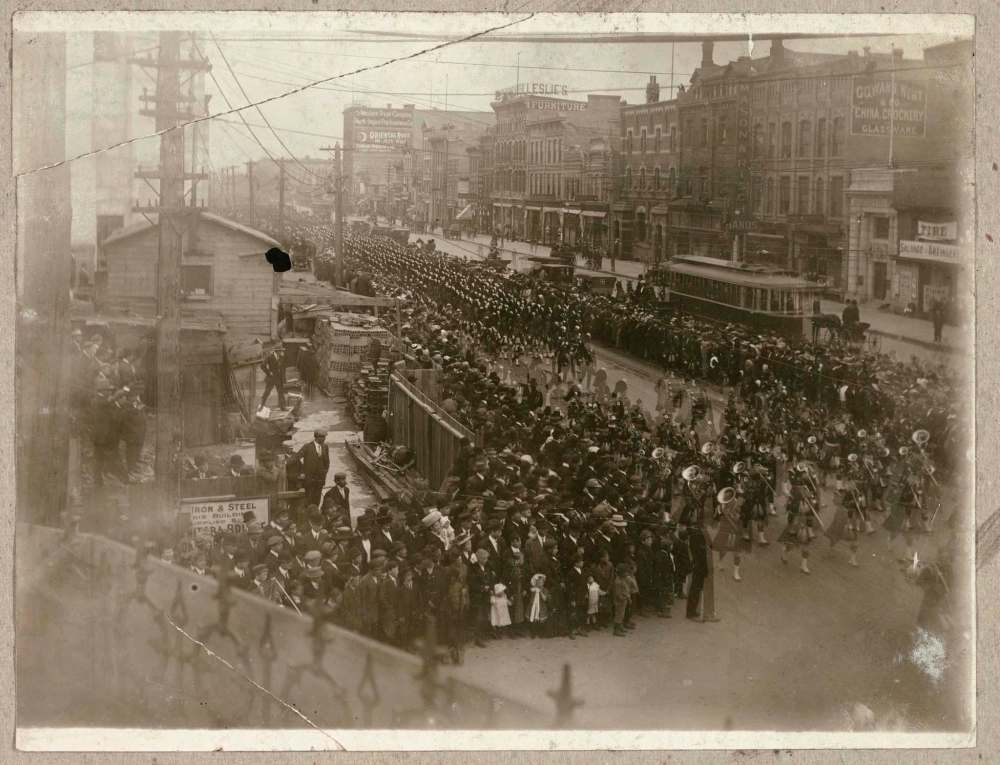

“Then as now most people saw Dominion Day as a day off from work rather than a day of special significance,” wrote local historian and photographer George Siamandas. “But there has always been a patriotic theme to the day. In 1915 three quarters of Winnipeg is described as having come out to watch the “spectacular parade.” Citizens in the thousands packed the city’s Industrial Exposition building, and 5,000 children assembled at a city school and then marched to the Exhibition grounds.”

Dominion Day took on greater significance, however, through the First World War. In 1917, the holiday fell on a Sunday and was marked in Winnipeg by a devotional ceremony, with a speech by Lt.-Gov. Sir James Aikins, to 6,000 people at the auditorium of the Industrial Bureau.

Under a canopy of Union Jacks and Canadian ensigns sat representatives of the church, state and military, the Free Pressreported.

“A massed choir of a hundred voices was seated on the second step of the platform together with the hands of the 100th Winnipeg Grenadier and the Salvation Army in full uniform,” the report said. “The service opened with the singing of the introductory hymn, ‘O Canada’ by the choir.”

There were even small Dominion Day ceremonies for the Canadian forces in France.

In his diary, now at the Manitoba Archives, Wilfred Conway Rutherford — a soldier from La Riviere enlisted in the 184th Overseas Battalion — described the events of July 1 to include four bands playing hymns while “an aeroplane hovers over our heads all through the service doing tricks that make us dazzle to watch. Yes marvellous dare devil tricks.”

A game of indoor baseball followed. Then “a barrel” of beer. Wrote Rutherford: “Many of the boys get best part drunk.”

Rutherford was wounded in the foot on July 23.

But what did it really mean to be Canadian? It was in the 1920s, in the wake of the First World War, where it appears the shedding of colonialism and the rise of nationalism began to take hold in the hearts and minds of average Canadians.

Take the example of William Lothian, who emigrated from Scotland and became a homesteader near Pipestone in his early 20s. Lothian grew up with the country, and in his late 60’s — despite having no formal education — he often submitted odes to his homeland to newspapers, such as the Montreal Witness.

“Young land of hope and promise, far flung from sea to sea; whose coming days hold destiny, of millions yet to be,” Lothian penned in 1916.

He even took a stab at writing a national anthem in 1926.

Jean Lothian, who married William’s grandson, recently dug up the writings in her Winnipeg home.

“He really wrote beautifully,” says Jean, now 84. “He just sort of had a foresight that it was going to be a great country. It was very moving, his insight into the land.

Then there are the writings of Frederick Philip Grove, who arrived in Manitoba from Prussia in September 1912. Grove became a teacher and principal in several rural schools, including Rapid City.

It was in that community, about 30 kilometres north of Brandon, where Grove penned an essay in 1928 called Canadians Old and New, which challenged his countrymen to abandon the colonial use of the term “foreigner” and it’s “sinister sound.”

“If the national status of Canada means anything at all, it means this: that here, in Canada, we cultivate… an attitude towards life and its various phases, economic, intellectual, spiritual, distinct from that of a mere British Crown Colony.”

And to those recent immigrants, Grove added: “If you think we want you to become in all things like the rest of we Canadians, you are mistaken. By becoming absolutely like ourselves — if such a thing were possible — you would lose the greater part of your value to us. Learn our language, obey our laws, and help us to make them when you have qualified for that function: that, Mr. New-comer, is all we ask of you.

“Above all, hold your head high. This country does not claim to be a ‘melting pot.’ What it does claim is here there are “many mansions” – and one of them, undoubtedly, is the mansion that has been waiting precisely for you.”

Of note, Grove wrote his essay just one year after the grand Dominion Day jubilee in 1927, which marked the first time the federal government made a concerted effort to stoke the flames of patriotism.

On Parliament Hill in Ottawa, before a crowd estimated at 60,000, “a moving and brilliant pageant, with music and oratory which… captured the imagination of the capital,” the Free Press reported. “It was a patriotic spectacle such as the capital had never witnessed before.”

In Winnipeg, the Free Press building downtown was decorated with giant Union Jacks for the occasion, which lasted three days over the weekend and included a national ceremony of thanksgiving, parades, military demonstrations and “throngs of people” in Assiniboine Park.

The festivities were hailed a “tremendous triumph.”

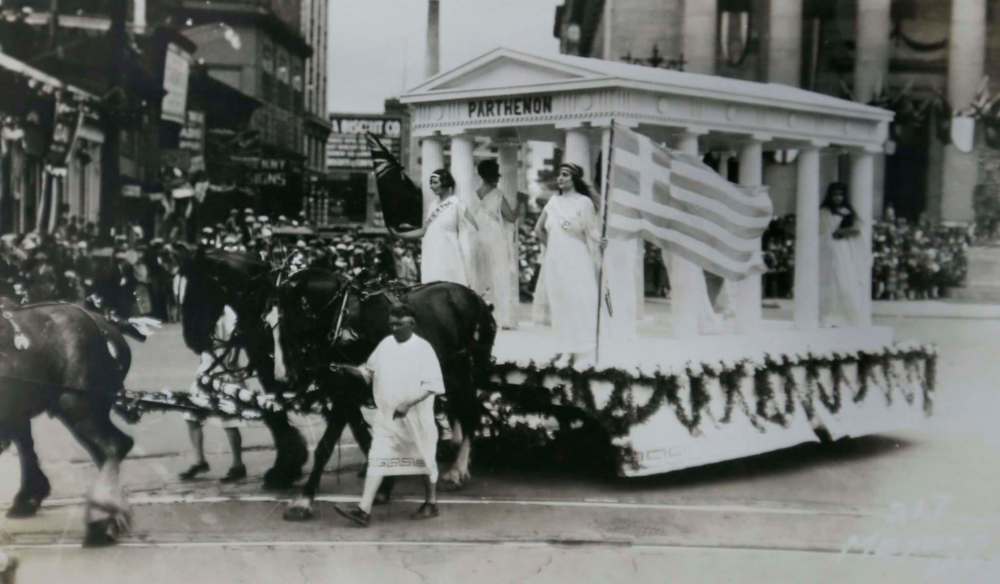

“The parade was the most magnificent that Winnipeg has ever seen,” the account read. “The great aim of the organizers was to get the progress that Winnipeg and Manitoba have made in the 60 years that have gone by since Confederation faithfully represented, and it was abundantly realized.”

And that was true. But here’s the real story:

The William MacKenzie government viewed the 60th anniversary as “an unprecedented opportunity to pluck recent immigrants from their bloc settlements and urban enclaves, and invite them to join the rest of the country in an ambitious, nationwide patriotic festival that was intended to integrate them more fully into the life of their adopted country,” according to a paper written by Mount Allison University history professor Robert Cupido in 2015.

Nowhere was that backdrop more evident than in Winnipeg, where the cultural and societal divide between recent immigrants and the Anglo-Saxon majority was stark and tension-filled.

Cupido’s paper was given the academic title of Public Commemoration and Ethnocultural Assertion: Winnipeg Celebrates the Diamond Jubilee of Confederation. But the more apt headline might have been: “The celebration that changed a city.”

Essentially, Cupido points out Winnipeg’s Anglo-laden city fathers, after an initial resistance, were eventually forced to incorporate more than 20 different ethnic organizations into the planning group. Those same ethnic groups, who had their own historic differences, were then forced to collaborate with each other.

“With the addition of dozens of New Canadians to various Jubilee committees, the city’s Anglo-Saxon elites for the first time found themselves collaborating with their ethnic counterparts in a major civic enterprise,” Cupido wrote. “For their part, representatives of the different ethnic associations (Poles, Ukrainians, Czechs and Russians, for example) were forced in many cases to subordinate their mutual prejudices and enmities to the common goal of impressing the charter group with their collective competence and patriotism.”

Legendary Free Press editor John Dafoe went so far as to claim that their shared experiences during the Diamond Jubilee “has given the people of various racial stocks a new viewpoint toward each other—the viewpoint that here in Canada, no matter what our racial origin, we are facing the battle of life together, that we all have more things in common than we have to keep us apart.”

The first Dominion Day after the end of the Second World War, in 1946, was another high-water mark for the celebration in Winnipeg, where the Free Press reported “16,000 people watched the races at Polo Park, others watched a baseball game at the Osborne stadium, some watched a parade, and thousands boarded trains to hit the beach.”

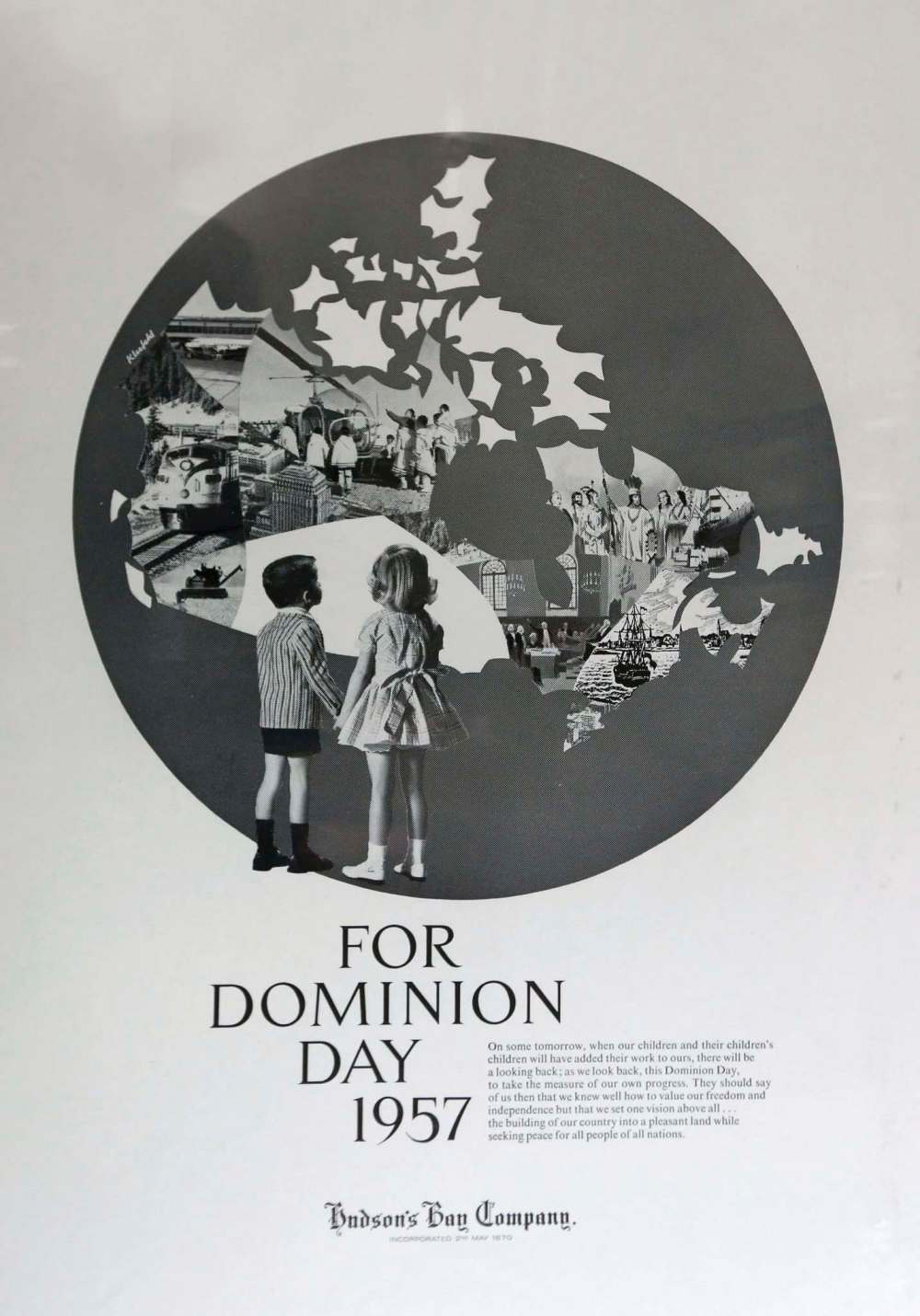

The term Canada Day emerged in the late 1950s, but it wasn’t until the early 1960s that the federal government once again deliberately began using the occasion to overtly further the notion of Canadian identity, Hayday notes.

Prime minister Lester B. Pearson, elected in 1963, organized a televised special on CBC, a variety show on Parliament Hill that featured performers from all 10 provinces.

But it was 1967, the 100th anniversary of Confederation, that elicited the largest Canada Day festivities in 40 years. Montreal had Expo. The Queen went to Ottawa to visit the old colony. Winnipeg was already gearing up for the Pan Am Games that would begin later in July.

A basic nationwide menu of parades, parties, barbecues, street dances, gun salutes and fireworks was spiced up with a local flavour here and there; a gathering of Scottish clans in Nova Scotia, a moose-calling contest in Saskatchewan.

Indeed, the centennial was essentially a year-long Canada Day, which included some mind-boggling displays of nationhood.

In Manitoba, that zeal was represented by a group of canoers who embarked on the Centennial Voyageur Canoe Pageant, a gruelling, 5,300-kilometre trek (including 100 kilometres of portaging) from Rocky House, Alta., to Montreal.

All 10 provinces were represented. The crew from Manitoba were victorious, edging the team from B.C. by two hours. In 2010, the winners were inducted into the Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame.

Canadians were leery of the Centennial at first. What’s the big deal?

“But once it started, that Bobby Gimby Centennial Song was playing on the radio, and there were TV specials. I think people got caught up in the spirit,” says journalist Tom Hawthorn, the Winnipeg-born author of The Year Canadians Lost Their Minds and Found Their Country (Douglas & McIntyre).

It didn’t hurt that the feds were priming the pump with million of dollars in projects — Winnipeg’s Centennial Concert Hall, for example — while stoking the patriotic fires. CBC commissioned Gordon Lightfoot to compose The Canadian Railroad Trilogy.

“Part of it was it was an innocent time,” Hawthorn adds. “America was having a very bad year, there were a number of urban riots in places like Buffalo and Detroit, in particular. I think Canadians thought, ‘You know, I’m really not sure what we have here, but it’s pretty good, even if we’re not able to describe it.

“For the first time since the celebrations at the end of the Second World War, there was a great swelling of national pride in 1967.”

In the latter half of the 20th century, the federal government has continued to use Canada Day as a friendly weapon, including fireworks, when national unity comes under threat.

In 1977, after cancelling most government-funded events to cut costs, Ottawa shelled out $3.5 million for Canada Day celebrations in the aftermath of Quebec’s November 1976 election of the separatist Parti Québécios; a 44-metre-long Canadian flag was draped on the Peace Tower in Ottawa.

With the prospect of separation became real in 1992, they brought out the big gun: Queen Elizabeth, who drew 50,000 spectators to Parliament Hill on July 1.

“Faced with continuing unity troubles, Canadians put on a generally atypical show of unabashed patriotism and frenzied flag-waving to celebrate the country’s 125th birthday yesterday,” the Free Press reported. “The crowd turned Parliament’s huge lawn into a sea of red and white as they waved Canadian flags, stuck them in pockets, hats and collars — even braided flags into their hair and painted maple leaves on their cheeks.”

These days, Canada Day in Winnipeg has come a long way from the settler’s celebrations. Sure, they still come to The Forks, but there are no cannons bolting them out of bed at dawn.

No one is climbing a greasy pole or goring an ox. But it’s still a party. There are concerts and face-painters and picnics. Assiniboine Park remains a destination on July 1, more than 100 years later.

And, perhaps, the notion of what Canada means to the average citizen hasn’t changed considerably, either.

Take the Danish-born Per Holting, who arrived in Canada on a visitor’s visa in 1950, and never left. Holting graduated from University in Ontario before becoming a CBC radio host.

The broadcaster travelled Manitoba extensively, often to report on First Nations or Inuit issues. During one program that aired in the mid-1960s, titled Life and Literature, Holting began by asking the question he was often asked: “Why did I come to Canada?”

“I do not know why I came, but I do know some of the reasons I stayed,” he concluded, “…a loon laughing at me for losing a fat trout; the feeling that I have when my plane approaches Newfoundland from overseas; an oldtimer telling me about his youth on the prairies; the people I’ve met from Great Bear Lake to Glace Bay and in the Arctic; the joy of seeing a bright yellow evening grosbeak when it’s 28 below, or the first robin of the spring; and, of course, I love the moments when I’m flat on my back, daydreaming about my future in Canada.

“I left a great little country to come to a great big one, and I’m still prejudiced enough to be overjoyed that our government decided to choose the Danish colors for our new Canadian flag. May the red and white fly forever!”

From modest beginnings, nations may rise.

randy.turner@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @randyturner15

Randy Turner

Reporter

Randy Turner spent much of his journalistic career on the road. A lot of roads. Dirt roads, snow-packed roads, U.S. interstates and foreign highways. In other words, he got a lot of kilometres on the odometer, if you know what we mean.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.