In a pretend opening ceremony at a divisive Olympic Games, China flexes. And hard

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Winnipeg Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*$1 will be added to your next bill. After your 4 weeks access is complete your rate will increase by $0.00 a X percent off the regular rate.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/02/2022 (1336 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

BEIJING—The last time Beijing opened an Olympics, the air was hot as soup and a soggy gunmetal grey, and this time frozen breaths steamed through masks into a clear smogless sky, and that’s what happens when you switch to a Winter Games. But time had passed, too. Things had changed.

And this time, at an opening ceremony that could have been a statement of intent, China hardly even tried. The 2008 opening was a declaration, or as the Washington Post’s Tom Boswell wrote of those Olympics, a behemoth being born. Over 4 1/2 hours, 15,000 performers moved in martial unison, drilled and united amid showmanship that practically bellowed to two billion people that China wanted more.

This was the song of a country that had gotten more. There was an LED floor, which is standard now, and a crooning performance of John Lennon’s “Imagine,” which may as well be written into the Olympic contract and should be excised from society until we can stop misusing it again. There were beautiful lights, earnest dancers, some fat glowing mascot pandas that looked to be fun to hunt. That should be an Olympic event.

But with the same director, Chinese filmmaker Zhang Yimou, it was smaller and less ambitious, and more, it felt so much less honest in tone. In 2008 China faked enough parts that people noticed: They snuck in pre-recorded fireworks, and the nine-year-old girl who sang “Ode To The Motherland” in the opening was lip-syncing, because the girl with the angelic voice everyone heard was deemed by a senior Communist Party official at a rehearsal to have teeth that were too crooked, and an overly chubby face.

Both times China included representatives from their 56 separate ethnic groups, including Uyghurs, who even in 2008 were being persecuted and were fighting back: Human Rights Watch issued a report before those first Chinese Games that included both Uyghurs in Xinjiang and the ongoing annexation of Tibet. Tibet got most of the attention then; there was even a Tibetan protest outside Chinese state television headquarters during the Olympics. But two days after the 2008 opening, Uyghurs in Xinjiang attacked a police station with homemade bombs, and five of them were killed. Fourteen years later, China’s forced re-education and detention of Uyghurs has led several countries, including Canada, to deem it a genocide.

The 56 ethnic groups in the 2008 ceremony were children, and it turned out organizers had just dressed a bunch of kids from the Han majority in separate ethnic costumes. This time they were adults who reverentially passed the Chinese flag to People’s Liberation Army soldiers and saluted before singing the national anthem. It was the kind of symbolism you get from a country that thinks it won.

Most of the rest was snowflakes and seasons and unity and peace. For China to talk about unity and peace could not have felt more perfunctory had it been faxed.

Which left the real politics in these genocide pandemic Games. Russian President Vladimir Putin had attended after an afternoon summit with Chinese leader Xi Jinping — the Chinese president’s first face-to-face with a world leader since the pandemic began — and Putin was caught on camera nodding off, or more likely pretending to, as Ukraine, a country with Russian troops massing on its Eastern border, marched in.

And in the parade of athletes, every nation gets to decide the general order, whether alphabetically or otherwise. China had decided on a linguistic formula that clumped Hong Kong and Chinese Taipei together. Chinese Taipei is properly called Taiwan, but China has more influence with the IOC, and in the opening order presented Taiwan and Hong Kong as twin colonies, one unconquered. As The New York Times noted, the Chinese state television broadcast referred to Taiwan by a name that, like Chinese Taipei, implied ownership.

Even then, it was relatively understated symbolism for a country that had been so hungry to proclaim itself the first time the Olympics came to town, in front of the world. Had China chosen disappeared tennis star Peng Shuai to light the torch, it only would have been surprising because the country has spent months trying to keep her under wraps.

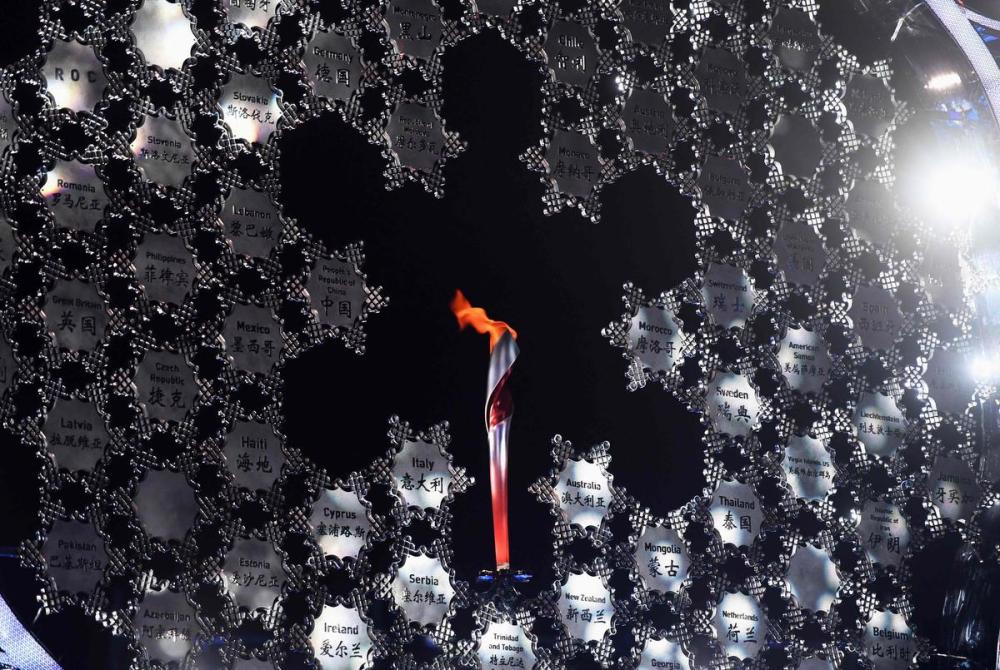

Instead, China went bigger. The final two athletes never actually lit the torch; instead they placed the torch in the middle of a giant glowing snowflake surrounded by children brandishing glowing doves, standing in the shape of a heart.

But, as in South Korea in 2018, it was the two athletes who mattered. In Pyeongchang it was two North Korean and South Korean women’s hockey players climbing a luminous staircase together before handing off the torch, after the North and South Korean delegations marched in as one, indistinguishable. That’s not the likely path of those countries, but it was an idea worth aspiring to.

This time the torch lighters were Zhao Jiawen, a Nordic combined athlete who is part of the Han majority, and Dinigeer Yilamujiang, a cross-country skier whom China has said has Uyghur roots. It was the moment China flexed, hard. If these are the genocide Games, China offered its rebuttal in the biggest moment of a show watched by billions: a happy, grinning, pliant Uyghur, supporting the motherland in front of the world. Openings are the songs you want to sing to the world. Not all of them are true.

These Games are already isolated, largely joyless, and even if saved by the athletes will be a trial. This opening was so much different than 2008, and maybe it was this: China still endured little protests around the Games in 2008 when it was not yet dominant but was on the way and needed to be heard, insistently, martially. It needed the world to know.

Now, 14 years later, China doesn’t need any of that, because it has mushroomed and grown and is what it said it was, and barely needs to pretend. This ceremony qualified as pretend, for the most part, but not entirely, not all. China has opened its Games.

Bruce Arthur is a Toronto-based columnist for the Star. Follow him on Twitter: @bruce_arthur