City’s expanding footprint has high cost

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/11/2019 (2202 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Planners at the City of Winnipeg are currently in the process of writing a residential infill strategy to guide new development in the city’s older neighbourhoods.

The task is challenging. People love their neighbourhoods and have a natural resistance to seeing them change. It’s difficult to use statistics to debate emotional attachment — mathematics rarely wins over the heart — but the hard numbers outline why planning policy has for many years promoted higher density infill growth, despite its unpopularity with residents.

Winnipeg has more old homes than any other city in Canada. Almost one in 10 houses in Winnipeg are older than 100 years, 10 times more than Calgary and Edmonton, twice as much as far older cities such as Montreal and Halifax. The mathematics suggests that change is inevitable for Winnipeg’s mature neighbourhoods.

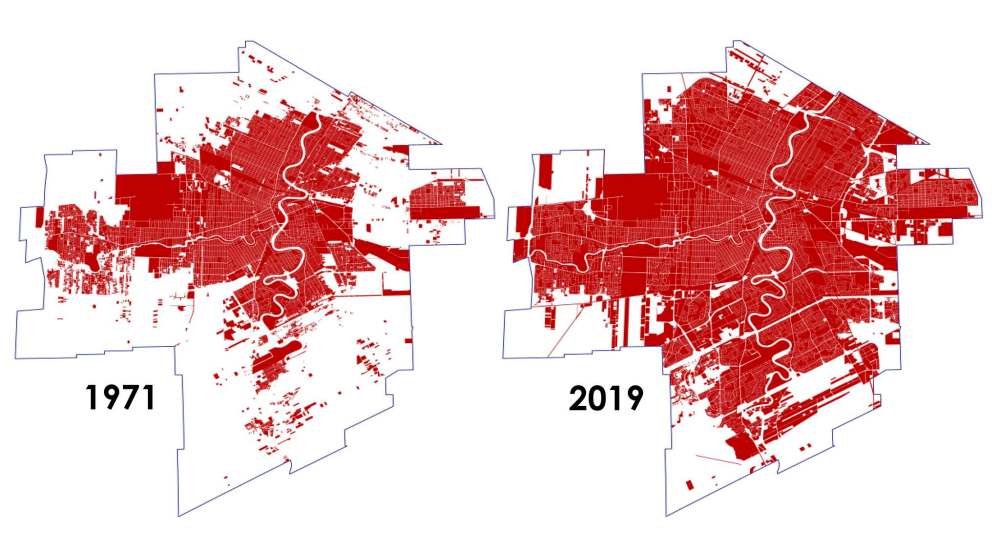

As part of its public consultation, the city recently released a jaw-dropping graphic that clearly explains why increasing density is considered a priority, as this change occurs. The graphic compares the built-up area of Winnipeg in the 1970s and today. In that time, the footprint of the city increased by 96 per cent, almost doubling, while the population increased by only 37 per cent. The conclusion was that the city is currently growing three times faster in area than it is in population.

Most people would say: “So what? We like our space.” But the economic repercussions are important to understand. Compared to 45 years ago, each individual Winnipegger is today responsible for the cost of maintaining almost 50 per cent more land area, and its corresponding services and infrastructure.

To put it simply, lower density means our tax dollars are stretched much further today than they once were. This is a fundamental contributor to rising taxes, declining public services and crumbling roads and infrastructure. When the area of snow that needs to be cleared from the roads doubles, but there is only about one-third more people to pay for it, the results are predictable.

This situation is only getting worse. With 91 per cent of all new residential development in Winnipeg’s metropolitan area occurring in distant suburbs, population density continues to decline every year. Older neighbourhoods have also become less dense, with most having 20 to 30 per cent fewer people living in them today than in the 1970s. Almost 90,000 fewer people live in all mature neighbourhoods combined, due in large part to changing household demographics.

This decline means that existing infrastructure such as roads, sewers, schools, parks, pools, arenas and libraries, is serving a much smaller population than it was built for, while at the same time, taxpayers incur the cost of new infrastructure required to support growing outer neighbourhoods.

Infill development can tap into these existing networks, reducing the public cost of growth, while the long distances of suburban infrastructure are both more costly to build initially and to maintain over time. As much as 70 per cent of Winnipeg’s civic budget is negatively affected by distance, including such things as snow clearing, transit, police services and road maintenance.

The economic impacts of this are significant. A study done for the Halifax Regional Municipality in 2015 determined that the taxpayer cost of providing services and infrastructure maintenance to a home in a new suburb averages $3,462 per year, while servicing a home in an existing mature community costs less than half that, at $1,416. The study found that even with higher suburban taxes, if 50 per cent of all growth could happen within Halifax’s existing footprint, more than $160 million in public money per year would be saved.

A recent, similar study in Edmonton found that the long-term servicing and infrastructure costs for 17 proposed edge communities will exceed their return in tax revenues by $4 billion over 50 years. In Calgary, it was determined that if growth could consume 25 per cent less land, the city would save $11 billion over 60 years in infrastructure capital costs alone.

The costs of a larger, lower-density city go well beyond its impact on taxes. In 1996, 37 per cent of Winnipeggers lived within five kilometres of downtown; today, that has been reduced to 28 per cent. Over the same time, the number of people living between 10 and 15 kilometres from the centre has almost doubled, to 21 from 12 per cent.

These greater distances mean longer commute times and more traffic congestion, resulting in lost employment productivity, and higher personal costs of vehicle ownership. Longer travel distances mean fewer trips using alternate forms of transportation, including walking and biking, which can impact public health-care costs and absenteeism. Winnipeg is the only major Canadian city where public transit use is lower than it was in 1996.

Increased driving also impacts Winnipeg’s carbon footprint, by creating higher levels of greenhouse gas emissions. Today, a full 50 per cent of Winnipeg’s emissions come from vehicles, by far the largest contributor.

Change in Winnipeg’s mature neighbourhoods is inevitable, and the economic benefits of higher-density growth likely means the forthcoming residential infill strategy will not be a barrier to infill, but instead a set of guidelines for developers and an outline of the minimum level of change residents will need to accept. To be successful, the strategy must find a balance between the cold statistics and the emotional connection people have with their neighbourhoods.

The city’s $7-billion infrastructure deficit is due in large part to the unsustainable, low-density growth patterns we have seen over the past 50 years. If the infill strategy is successful and we do end up building higher densities with less new infrastructure, we will be passing the next generations a more prosperous and sustainable city.

Brent Bellamy is creative director at Number Ten Architectural Group.

Brent Bellamy is creative director for Number Ten Architectural Group.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.